Drawn and Quartered

Montreal's plan to turn a square kilometre of downtown real estate into a “republic of culture" has left smaller arts communities afraid for their survival

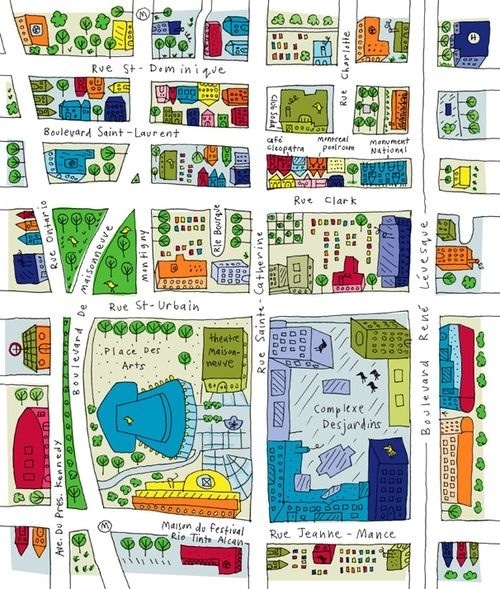

Illustration by Tania Howells.

IT’S SATURDAY NIGHT, and Café Cleopatra is on red alert. While the striptease show continues downstairs, upstairs—a hotspot for Montreal’s resurgent cabaret culture—is a party aimed at saving the landmark strip bar from destruction. Patrons crowd the three-quarter stage to watch a local skateboarder deliver a PowerPoint presentation. Cleopatra’s soft-spoken proprietor, Johnny Zoumboulakis, paces the room with his hands folded. An older man in white paint, fake blue lashes and a paper tutu hands out blinking Dora the Explorer pins.

The presentations are punctuated by glitzy performances from burlesque dancers and drag queens, but offstage their faces betray anxiety. The area of St. Laurent Boulevard where Cleopatra resides—a stretch of boarded-up storefronts south of Ste. Catherine street—will be razed as a gateway to the Quartier des spectacles (QDS), Montreal’s newly branded entertainment district. Along with a renamed metro station (“Saint-Laurent-Quartier des spectacles”), twelve-thousand-square-foot theatre (Theatre Telus) and eco-friendly boutiques, the $167 million overhaul will see the creation of two slick buildings: on the east side, an eight-storey cultural centre; and on the west, where Cleopatra stands, a gleaming twelve-storey office tower to house Hydro-Québec, the province’s electrical provider.

Supporters defend Cleopatra, which has been around since 1975, as a vital part of the city’s cultural heritage. The argument hasn’t swayed developers, who insist there is no time to dawdle. Due to Hydro-Québec’s needs, ground must be broken by January 2010 for office workers to move in by 2012. To meet this deadline, the two QDS buildings—named the 2-22 and Quadrilatère, respectively—will require the relocation or expropriation of current block tenants, which include four show venues, the country’s first Lebanese grocery, and the Montreal Pool Room, a renowned ninety-seven-year-old hot dog diner. In the name of preserving heritage, the old buildings’ façades will be incorporated into the Hydro-Québec tower, but not their interiors.

Overseen by the Angus Development Company, these plans have pushed the Quartier des spectacles into controversy. Christian Yaccarini, Angus’s wild-eyed and loose-lipped president, hasn’t helped; he revealed in June that he had offered $2.5 million to Cleopatra, fueling concern that land speculation will balloon property values beyond what anybody can afford.

Even neighbouring businesses who are allowed to stay have started to worry. “This is destroying the street,” says Michel Sabourin, owner of Club Soda, a concert venue across the street from Cleopatra. “Once you put a building like that up and break the existing zoning regulations, it’s only a matter of time before another and another go up. We’re not rich here. I’m worried whether we will be able to stay here five, six, seven years from now.”

City officials hope the QDS will make Montreal an international cultural destination, with the added bonus of cleaning up the former red-light district. But at the heated public consultations on the project this year, independent artists and cultural entrepreneurs wondered why only selected arts are worthy of the QDS’s largesse—and why the project is displacing some of the very spaces that give the city its edge.

One such critic is producer Eric Paradis, who uses Cleopatra’s cabaret stage for rehearsals and shows. A former dancer and musician, Paradis likes to wear his dark hair long and often pairs cuffed sleeves with leather pants. “We are in the Quartier des spectacles,” Paradis told me over coffee at a Ste. Catherine café. “We have to include the spectacles du quartier.”

MANY MUNICIPALITIES have changed the way they think about growth, shifting away from industrial manufacturing toward a service- and “knowledge”-based economy. In his influential book The Rise of the Creative Class (2002), Richard Florida declares that the so-called “creative class”—scientists, engineers, as well as artists, designers, writers and musicians—is key to this new economy. The future of urban centres, he argues, lies in guiding this “super-creative core” toward productive ends.

Montreal has never been a stranger to spectacles, but in recent years, the city’s political heavyweights seem to have taken Florida’s advice to heart. At a 2001 summit, Montreal decided to actively integrate cultural development into municipal planning, with the QDS emerging as the crown jewel of this new focus. The city is a natural fit for such an ambition. The downtown core boasts eighty cultural venues, thirty performance stages and nearly twenty-eight thousand seats. It is also host to two of the city’s festivals: the Montreal International Jazz Festival and the Just For Laughs comedy festival, which each attract some two million annual visitors. The Jazz Festival alone is estimated to pump about $150 million into local coffers.

The plan was to promote the area’s arts and performance spaces, reserve more public space for festivals and increase pedestrian traffic through the neighbourhood, thereby drawing more tourism and cultural investment. In 2002 the director of a newly created lobby group, Culture Montréal—which later provided funding for Florida’s 2004 study on Montreal—told the Board of Trade that the city ought to frame its future as a “republic of culture.” Straight out of a Florida textbook, Simon Brault told the Board, “If Montreal wishes to lay claim to being a world city that values creativity and innovation, it must without delay make a number of choices that clash with the traditional view of the city as an administrative entity mainly concerned with issuing permits and collecting garbage.”

Mayor Gérald Tremblay assembled a team from the cultural, corporate and civil sectors for the Partenariat of the Quartier des spectacles, which eventually secured $120 million in federal, provincial and municipal funding. Millions more have come in from private corporations, notably SNC-Lavalin, for a new symphony hall, and Rio Tinto Alcan, for a new Maison du Festival du Jazz. The Partenariat also worked with designers to develop the QDS neon-glow logo and signature red LED circles projected onto the sidewalk (done in homage to the area’s history as a red light district—a district the QDS will slowly replace).

The QDS winners are clear: a group of cultural associations that will be housed in the 2-22 building at the corner of St. Laurent and Ste. Catherine; Hydro-Québec, the new tenants of the LEED-certified Quadrilatère building; and the city. “This is very, very important for Montreal’s tourism,” says Pierre Bellerose, a spokesperson for Tourism Montreal.

But according to a source close to the Partenariat, the board room has grown divided over the direction of the revamp. “A lot of projects in the area are rapidly going forth, and as they progress are totally losing their initial objectives,” the source says. “The whole hope of consolidating this space as an area for cultural expression, for discovery, for innovation, seems to be increasingly lost.”

MONTREAL IS FAR FROM the first city to promote cultural areas downtown. Toronto’s Distillery District made sure to set aside affordable studio space amidst an influx of condominiums. Vancouver is negotiating funding for the renovation of its storied cabaret stage, the Pantages Theatre, near the Downtown East Side. The Pittsburgh Cultural Trust uses income from higher land value to create affordable cultural spaces downtown.

In each case, urban planners and developers were mindful of one of gentrification’s most harmful effects: driving out the very “creative class” that first drew attention to the area. Early planning documents for the QDS demand that development adhere to a principle of “equilibrium,” which would preserve “an invigorating marginality while remaining safe and secure.” But housing group Habiter Ville-Marie has complained that the call has been ignored. “Lodging for modest or low-income households,” according to its report, “remains nonexistent.”

Pierre Fortin, the general director of the QDS partnership, admits that not enough has been done to secure affordable artist studios or residential space, calling it “something that will have to be addressed.” But this is something that Richard Florida’s many critics have warned about. They point out that his focus—designing municipal policies that encourage creativity-driven growth—can easily backfire by driving up property costs and chasing away the arts scene. But Florida has preferred to emphasize the economic benefits of culture-friendly municipal policy—not its potential social drawbacks, or, for that matter, its effect on the arts themselves. “I fear that when the haphazard efforts to ‘implement’ creativity fail to produce the predicted economic magic,” writes Austin-based arts consultant Ann Daly, “art and culture’s shining star will fall as quickly as it rose.”

The source near the QDS echoes Daly’s sentiment. “The problem is, now you’re looking at a mega-project, and it’s an all-or-nothing scenario. There’s no opportunity for individual failures anymore. Everything has to succeed or everything will fail,” the source says.

As a result, small venues and festivals, which have played their own role in making Montreal an international culture destination, are struggling for attention. Compared to the QDS’s hundreds of millions of dollars in investment, this year saw just a $90,000 grant given over three years to the city’s Association of Small Art and Performance Spaces. Also this year, a new Industry Canada grant was announced for festivals—but only “marquee” festivals, with attendees of more than fifty thousand and an overnight touring plan, need apply. Just For Laughs and the Jazz Festival have already secured a significant chunk of this funding.

Patricia Boushel, a producer at the celebrated Pop Montreal music festival, laments that the city’s vision of promoting culture has amounted to supporting “hyper-funded areas of the arts—for artists who have gotten over their developmental phase,” instead of for the smaller venues and creative forces at work on the edges. “As far as the city is concerned,” she says, “the only festivals of value are Just For Laughs, Cirque du Soleil and the Jazz Fest.”

Faced with a disinterested city, six of Montreal’s small festivals have organized their own alliance called Le Regroupement. At the public launch of the alliance—at the Monument National, just twenty paces from Cleopatra’s doorstep—I spoke with Patrick Goddard, general manager of the Montreal Fringe Festival. Goddard, a red-haired anglophone, once wrote a play about Pax Plante, the head of the Montreal police’s infamous Morality Squad during the 1950s, who oversaw the first big “clean-up” of downtown under Mayor Jean Drapeau. “I do feel a bit of déjà vu,” he said of the plans to raze and rebuild the lower Main.

The idea for Le Regroupement, Goddard told me, came after a meeting with Just For Laughs director Gilbert Rozon, who had approached the smaller events with an ambition to make Montreal “the new Edinburgh” by organizing all festivals in the same month. Most smaller festivals have international festival circuits or alliances, Goddard explained, and moving their times would disrupt a well-functioning system—in other words, among niche arts groups worldwide, Montreal is already an international destination. “We were all in the elevator on the way down from that meeting, and we just looked at each other and realized, maybe we should talk,” Goddard said.

THE QDS PUBLIC CONSULTATION process last summer drew a spectrum of characters, from academics to burlesque dancers with names like Felicity Fuckhard. But after many long nights, nerves grew frayed. Outbursts of indignation often erupted from a row of Angus’ supporters, which included the director of the pro-development Theatre du Nouveau Monde—who is also Yaccarini’s girlfriend. On the other side, local art promoters displayed film clips from Cleopatra’s cabaret shows, some of which included risqué shots of fetish performances.

Not all had the courage to come forward. Dennis Hadjiev, the twenty-year-old son of the Pool Room’s owners, said he wasn’t “political enough” to speak. “If I went up there, I might cry,” Hadjiev told me under his breath during one presentation.

Angus President Yaccarini grew increasingly impatient throughout the consultations surrounding his company’s proposal. Near the end, he sent an email to colleagues and the press, calling the consultations a “veritable psycho-drama” where “so-called artists” were putting the city’s development at risk. He ridiculed “certain architecture professors”—the head of the University of Montreal’s architecture department called the project a “banalization” of a historic area—for suggesting it would be better to “do nothing for the sake of heritage.”

When the public consultation commission released its review of the project in August, it pointed heavy criticism at both the rushed timeline and the development’s designs (which it called “façadism”), but made no explicit recommendations for the integration of the street’s current tenants into an office tower or shopping complex. The city is under no obligation to heed any part of the report. Indeed, days after the public consultation meetings wrapped up, Mayor Tremblay reiterated his commitment to help developers begin their projects “as quickly as possible.” If Angus is unable to negotiate purchases, City Hall may expropriate remaining tenants, something it did last year to get rid of a peep show and pizzeria near the new cultural building. In the meantime, some QDS development has already taken hold. Stevie Wonder headlined the Jazz Festival this summer, with some 150,000 people cramming into the new outdoor Place des Festivals; on the other side of the block, construction is underway for the symphony hall.

Yaccarini insists that he does not want to “whitewash the neighbourhood,” and has offered to find a place for artists on adjacent Clark Street. The Montreal Pool Room has already agreed to move, but holdouts are digging in their heels; Cleopatra’s supporters have created a Facebook page, and are organizing a contest to propose new architectural ideas for the block’s development, as well as a Red Light Festival to celebrate the area’s heritage.

The source close to QDS regrets that the debate had turned sour. The Café Cleopatra controversy “decayed into a moral debate about what culture is right and what is wrong,” the source suggests, “when really they have just as much a right to be there as anybody else.”

Not according to QDS planners. Despite Café Cleopatra’s popularity, and the renaissance of burlesque, Anne-Marie Jean, the current president of Culture Montréal, dismissed the venue. “I was told of their activities,” she says, “and from what I understand, they’re not spectacles.”

See rest of Issue 33, Fall 2009.

Read Kelly Ebbels' follow-up report "Mile End vs. Morality Squad."