How to Act When You're Not Acting

Three ideas for the underemployed thespian.

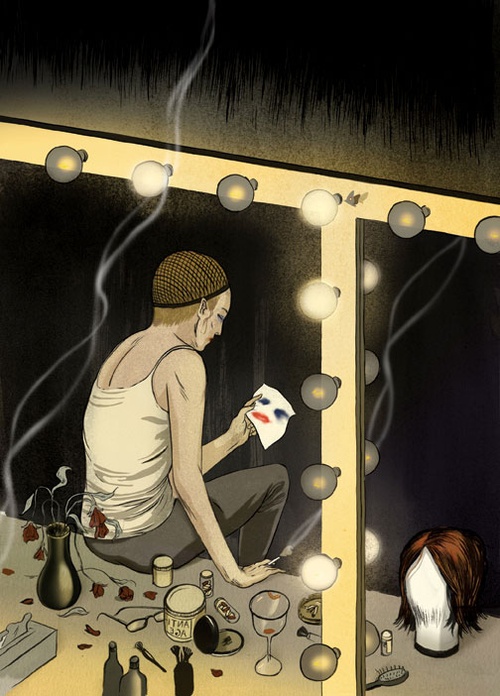

Illustration by Byron Eggenschwiler.

I recently spent a week on one of the Gulf Islands off the coast of Vancouver, a place now largely populated by lawyers who were once hippies—people who somehow had the good sense, back in the sixties, to buy land. For decades, they have been coming together for dinners after spending their days chopping firewood, and I was invited to one of these meals. Twelve people sat around the table, including a woman in her late forties. She was blonde with wide-set eyes. She had the tense, dry look of an actress who no longer worked, which is what she turned out to be. She had done some CBC movies and B-movies in her day, and now taught drama to kids. "I am old," she said, "and I am ugly." She referred at least four times to her "Russian" cheekbones and reminisced about her early, energetic days as an actress in Edmonton. Her whole monologue, her self-presentation, made my rhubarb pie taste like sand and dust. There are few conversations that spoil a meal more than the story of an actress who has outlived her career.

What do we do once we can no longer do what we did? It's a problem for anyone, but it seems to affect the actor most acutely. Even when an actor is working, it's not unusual for her to go entire weeks or months without a part. The customary thing is to take acting classes, work undemanding jobs, exercise, meditate, see friends, read plays. The actor's life is about finding ways to fill in the time between gigs. Even when one has an acting job, there is still a lot of waiting around: while the lights are being moved, while makeup is being done. Once the actor's career is over, I imagine there is still a sense of waiting, as though the spotlight might eventually return.

Sitting across from the actress at that dinner, I wondered how an actor might root herself, artistically, in these downtimes or after her career is finished; that is, how an actor can always act, and learn better how to act, and make the world better by acting.

Charity

I don't want to say that the actor—more than any other person—should spend her life in a charitable manner. But if the actor wants to imitate an action, what could be better for the world—and her own self—than to imitate selfless giving? Why shouldn't the actor, in her off-hours, put herself at the disposal of old people, sick people, people who need help, and act the part of someone who cares? Acting caring leads to caring, and in this way actors might turn themselves into the most helpful and fulfilled of all the artists. As it is, many actors can hardly take their eyes off themselves. The actor in this scenario must use her narcissistic qualities to imitate the action that will bring her the most praise. Eventually, she will become worthy of genuine admiration. This discipline would be called "Acting Your Opposite."

Performance for a novelist

Once in a while, actors should put themselves at the disposal of writers. What writer wouldn't benefit from sitting in her easy chair and listening to an actor read out her day's work? Playwrights know that it's impossible to tell whether what they've written is good or bad until an actor speaks it out loud. Novelists rarely think this way, but they could. After all, readers speak the book silently to themselves in their heads. An actor reading a novel out loud is a simulation of the reader's experience—the closest a novelist can get.

The hidden problem for the novelist is that she only ever reads her work one way, forgetting that there are so many meanings in any one sentence, so many different intonations and interpretations. This way, the novelist can hear her words in someone else's cadence. As a reader, an actor could make herself very useful, and she would gain from performing for an audience of one—an audience who cares deeply about the words being spoken.

Impersonation

One of the sad and strange—and perhaps most beautiful—things about humans is that there is only one of each of us. In our culture, the problem for any individual is how to be oneself most "authentically." The problem for any actor is how to best play a given part. The ordinary person strives to live in tune with her own wisdom and intelligence, her sense of what is right, her instincts and inclinations. The actor attempts to uncover these things in each role she plays.

Could there be a service that connects—for a lifetime, or some shorter length—an actor with an ordinary person, with the actor acting as that person's clone? The actor would try to dress, speak and move like the person she is cloning (let's call her Abigail), and poetically interpret her. She would try to understand Abigail's cognitive pathways and emotional responses. There would never be a performance, just a perpetual following-around of Abigail. She would read Abigail's emails. She would meet with Abigail's friends when Abigail is too tired. Trying, on a long-term basis, to get outside of herself and into just one other role would teach the actor so much more than any single theatre class. Most of the secrets of human nature lie in the distance between who I am and who you are.

The actor would then become like a painter or writer, whose whole life is given over to the perfection of a master work. The in-between jobs would turn into gigs taken for money, like journalism often is for the novelist, or wedding portraits for the painter. The acting in those "in-between jobs" (that is, roles in plays, films and television) would become much more lifelike. This actor would know what a person truly was like from her ongoing imitation of life. And how endless this task of imitation would be, since Abigail would be changing week in and week out, as humans supposedly do.

As for Abigail, she would get what many people secretly loathe and crave: a witness and a mirror. To see oneself portrayed through the gestures of another person, to see oneself interpreted, is to know what we otherwise never would: how we appear to the world from the outside. I would hate to have an actor following me around, but why should everything be so comfortable? Maybe having these real-life imitations would allow us to live in greater proximity to our insides—closer to our motivations and our fears.

I do not want to be an actress, yet I grew up wanting to be one. I acted and wrote from the time I was a child, but it gradually became clear to me that I was not good at acting. Though I had enthusiasm, I knew there were people who, while acting, had feelings I did not. As I acted, I looked at myself with skepticism and shame.

Yet the person who is an actor in her bones—who needs to act but has to wait for an opportunity that doesn't always come—probably dies a little from misuse. An actor who cannot act is like a cat that cannot lick its own fur. Every creature has its own nature, and happiness is being able to express that nature.

Of all the options I suggest for the actor, I think the last one—while the most unpleasant and dangerous—is best. Only when we throw ourselves into danger is anything of worth accomplished. We live in our cities, in our little homes. But we are animals, and we are primed to respond to threat. When we live lives with no real danger, our instincts find things that are not dangerous and make them dangerous. So why not invite into one's life something genuinely horrifying, and come face to face with oneself?

We should all have actors trailing us around. This would mean that all the other truly non-dangerous areas of our lives would lose the sense of terror they currently carry. We would begin to feel real fear. As Mark Edmundson wrote in the New York Times:

Shakespeare's fools are subtle teachers, reality instructors one might say... Hamlet gets Yorick; Lear gets his Fool; Olivia, Feste; Rosalind, Touchstone... In Shakespeare, to have a fool attending on you is generally a mark of distinction. It means that you've retained some flexibility, can learn things, might change; it means that you're not quite past hope, even if the path of instruction will be singularly arduous. To be assigned a fool in Shakespeare is often a sign that one is, potentially, wise.

What actor doesn't want to be helpful—to be a fool? Now go and find an actor to follow you around—you who want to change, to become wise.

Originally published in December 2010. See the rest of Issue 38 (Winter 2010).

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Human Behaviour

—Where Have All the Monologues Gone?

—Interview With Sheila Heti