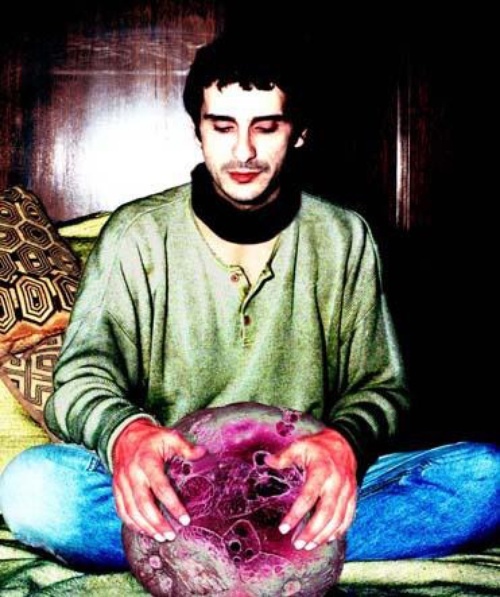

Interview With Abou Farman

The writer discusses his new book, private spaces and why nobility isn't a good thing.

Boredom was one of the key factors in Abou Farman's development of his first book, Clerks of the Passage (Linda Leith Publishing). He explains to me that the book had "been in movement from the very beginning ... Maybe when my mother first quickened." Originally, "it was a bunch of oral histories of Iranian refugees leaving Iran. On the other side, I was doing a series of personal essays that I did conceive as a kind of a book. But I got really bored of personal stories, my own and other people's ... And to the consternation of some, I dropped that project and I ended up turning it into this more abstract way at arriving at some of the same issues."

The result is a collection of meditations on migration in which Farman—anthropologist, writer and artist—connects mobility with, among other things, the invention of photography, diverse conceptions of heaven and the drama that accompanies crossing a border. He addresses those of us still waiting for our Godot.

Farman is a long-time Maisonneuve contributor, and he will launch Clerks of the Passage tomorrow at Casa del Popolo in Montreal, an event that also serves as the launch of Maisonneuve's Fall issue. I spoke to him over the phone while he was in New York, where he is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Bard College.

Erica Ruth Kelly: One of the first things that struck me about the book was how seamless it feels, in that it manages to move from one topic to another within a single chapter, without any signposts that say, "You're here now." How did you accomplish this?

Abou Farman: Well, I'm sure the seamlessness is in the mind of the beholder. Maybe it's in my mind, also. One of my problems was always that I was fearful that people wouldn't see it as seamless, because in my mind, it was.

It's really what happens when you follow your ideas around one topic. If the topic is unified enough—in this case, movement as an abstraction from migration, and then if you're exploring all its less visible contours—it will remain coherent. I basically followed my nose as far as I could. In other words, if I got serious about something, I would just try and take it as far as it would go.

ERK: "Ali" is used as the name of different migrants in Clerks of the Passage, and your book shows an interest in etymology. Given that "Ali" can mean "noble," among other things, do you think there is something noble about the traveller?

AF: I never thought of it in terms of being noble. My association with nobility... is with social status. So I don't regard it very highly, nobly. But yes, what I think is precisely excellent about a certain kind of migrant is that migration and displacement tend to question social status, precisely by virtue of a person not being where they're supposed to be, not being in a specific status, being outside of status. If anything, in that sense of nobility, the migrant is the anti-noble, in the sense of the social status as designated by that word.

ERK: Referring to various characters as "Ali" lends to the abstraction of their identity. Your use of the pronoun "you" also seems to achieve this effect, and to sometimes make the reader feel involved in the story—for example, in the scene in which Ali arrives at immigration: "Ali didn't want to go up to the officer with you there seeing everything. He didn't know you, you didn't know him and it would make no difference, but still he didn't want you to witness him get escorted away by uniformed officials, handcuffs dangling at their side." Was that done to achieve the same level of abstraction as with the word "Ali"?

AF: Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that the abstraction of identity is not a way for me to escape identity but to implicate identity. In other words, exactly the feeling that you describe in terms of being implicated by the direct address. I think that's what I want from abstraction, for people to fit in there, where specificity might be a way for people to feel more distance. I also think that the use of different kinds of pronouns in writing has proliferated in interesting ways, novels entirely written in the third person plural and stuff like that. I'm always attracted to that. I like the fact that the use of the pronoun in different ways can have different effects on the reader.

ERK: You describe home as being "principally made up of your private corners, the places where you bunch up on your own to recover, to remember, to disappear and to re-emerge." Location, however, doesn't seem to fit into this. Do you think home is location-based? And could it, in some ways, be an activity, as people often say, "When I'm doing xyz, I feel at home"?

AF: It is an activity; it's an activity of self-fashioning, in a sense. In my conception, it is not location based. But it is linked to space. I think one needs an interaction between the space that you're in, that you're occupying, and that sort of inner movement. That's what your private spaces are. That idea comes from kids and their hiding places, which are places where kids generally go to find themselves to recover from the assault of the adult world and so on. That's my idea of home. Not to say that it's a refusal to grow up or anything, but it's based on that notion of hiding places where you prod yourself and fashion it in ways that are different from the way you fashion your public self. I equate the meaningful parts of home with that. The location might shift, but it always requires an interaction with a space.

Abou Farman and Maisonneuve will team up tomorrow night for the joint launch of Clerks of the Passage and Maisonneuve's Fall issue. The event takes place at Casa del Popolo (4873 St. Laurent) at 5 pm and is free. Check out the event on Facebook.