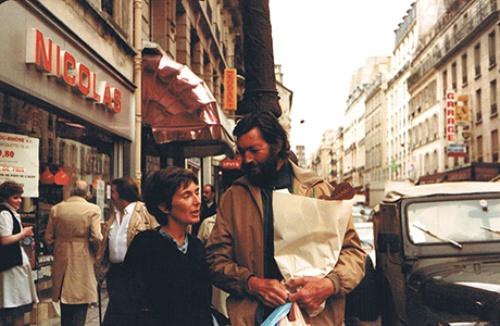

Photograph by Jose Alias.

Photograph by Jose Alias.

The Parallel Highway

The Montreal writer Carol Dunlop and the Argentinian novelist Julio Cortázar carried out one of the greatest literary love affairs of the twentieth century. But their romance was shadowed by tragedy.

SHE CALLED HIM EL LOBO, OR THE WOLF. He called her Osita, Little Bear. Their ride was Fafner, a 1970s Volkswagen camper van, candy red, shaped like a caterpillar and named after the dragon in Wagner’s Ring Cycle. On May 23, 1982, Julio Cortázar, the famous writer, and his young wife Carol Dunlop set off to explore the uncharted territory of a French highway. They faced an almost-800-kilometre journey along the Autroroute du Soleil. The drive, typically ten hours from Paris to the port city of Marseille, would take them thirty-three days.

They were writing a book about the autoroute to uncover what lay beneath the banal, to see what happens when you travel at a snail’s pace along a stretch of asphalt designed for exactly the opposite. They’d explore each of the sixty-five rest stops along the route and camp at the second each night. The rule was they could never leave the highway: no day trips to Dijon, no walks into wine country, no grocery runs. They plotted for their friends to meet them on the eleventh and twenty-first days to drop off a cargo of fresh supplies. Fear of scurvy, after reading too many explorer books, had pushed Cortázar to plan ahead.

They packed two typewriters and a camera with the intention of documenting their exploration as it happened. The result would be Autonauts of the Cosmoroute—a cult classic published in French and Spanish in 1983 and today in several languages.

Three decades later, fans of the book retrace the voyage nearly every year. From a Spanish woman who made the trip with her first husband—and is now seeking a new man to do it with—to a mad thespian in Paris who packed his own hippie van full of actors and had them perform the book, page for page, in real time, people retrace the Cosmoroute as a sort of pilgrimage. Like all pilgrims, everyone who takes the trip does so searching for meaning beyond the path itself—which is exactly what Cortázar and Dunlop had in mind when it all began.

On the second day of the journey, Cortázar parked Fafner under some trees and set off on foot to explore a small trail a few metres from the highway, leaving Dunlop to fill in the log book. Over the coming weeks, she would keep track of the little things: the meals they ate, their position on the map, the storms they’d endure at night as they made love in an intense and unbreakable solitude. A few minutes later, Cortázar came running back to the campsite and tapped her on the shoulder. “Osita,” he said, “over there, you’ve got to go see.” She put down the pen and hopped out of the Volkswagen.

“Okay Wolfy,” she said. “Let me take a look.”

ACCORDING TO PABLO NERUDA, you had to read Cortázar or else you’d be doomed. Cortázar, a writer who grew up in Argentina and lived most of his adult life in Paris, sparked the Latin Boom with Gabriel García Márquez in the 1960s. Thirty years after his death, Cortázar is still read by millions and continues to top bestseller lists. This year would have been his hundredth birthday and marks the release of Cortázar de la A a la Z, an encyclopedia of his life.

They still write about her in the newspapers in Latin America and Europe whenever they write about him. Dunlop is known as the Canadian wife, the third wife, the one who accompanied him on his final voyage and wrote his final book with him. But before she was Osita, she was a small-town girl with a prodigious talent for writing and a thirst for escape. Hell, she wasn’t even Canadian.

You ask Dunlop’s only son, Stéphane Hébert, about her upbringing and he’ll tell you a white-picket-fence story. She was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. Dad was a former marine who worked at the Gillette factory. Mom was a bank teller with a pair of cat-eye glasses. Dunlop danced ballet. But skip through the sepia shades of the family photo album and the colour photographs emerge. The Canadian parts fill in. In one of the photos, with hair cut to her shoulders, she is bent over an acoustic guitar. Hébert describes her as a rebel who didn’t fit in the United States. She left the US during the Vietnam war, he said, and “she never went back.”

She came to Montreal at eighteen and found a world filled with poetry, terraced cafés and pipe-smoking intellectuals. Like Samuel Beckett, she’d adopt the French language for her writing. (She once told a friend that writing in English was “too easy.”) She even married a writer named François Hébert, one of those Montreal intellectuals. In 1968, they gave birth to Stéphane. Both of them, as seen in their letters at the time, were focused on getting published. But for Dunlop, writing was also about escaping a darkness she carried—one she thought she could will away with the typewriter.

In 1970, Yvon Rivard, a friend and Montreal-based writer, spoke with Dunlop. “She was practically out of breath,” he said. “‘Yvon,’ she told me. ‘I have found the perfect book.’” Dunlop had read a collection of Cortázar’s stories in one sitting.

“OKAY, WOLFY,” she said.

She walked to where El Lobo had pointed. She came to a fence and, beneath a white flowered tree, found a gate left wide open. Out over a dark and rolling landscape of black grass fields the clouds over a hazy, rain-washed Paris were visible in the distance. This was the world they had escaped and now, after only one day on the road, temptation to transgress the boundaries they had set for themselves. Why had El Lobo sent her to go look? Had he cheated already? Osita ran all the way back to Fafner like a spooked child and found him, giant headphones on, lost in his music in the driver’s seat. She cut an apple in two and said nothing of the bait.

DUNLOP HAD SCARS ON HER BACK, an illustrated history of the time she and her brother were cruising on his motorcycle and he lost control. She only suffered skin loss—her brother, one friend whispered to me at Café Dépanneur in Montreal’s Mile End, dragging a hand across her throat, was decapitated. Dunlop rarely spoke of it to anyone.

She had another secret that not even those closest to her knew much, if anything, about. She was suffering from a disease the doctors couldn’t diagnose. One old friend, a man who fell in love with her at his senior prom, remembers suggestions that she had leukemia. The illness started getting serious in the mid-seventies. Dunlop would disappear for days, forced to undergo blood transfusions that would confine her to a hospital bed. She and Hébert separated. “We have no idea what the hell it was,” says her old friend Francyne Rivard Trottier, Rivard’s ex-wife. “We never figured it out.”

I met Rivard Trottier across from her old duplex on Bernard Street in the Mile End. “She had me take this photo on her death bed,” Rivard Trottier told me, holding up a picture of a young Dunlop in 1977, glasses big and round, a face dour and marked with shadows. She had stopped her treatments. Hébert visited with their boy. Dunlop wrote a poem about the incessant ocean and a suffocating dawn that she thought would be her last. But her parents showed up a week later. Her father took his little girl in his Marines-trained arms and rushed her to the Jewish General.

She remained undiagnosed, but she lived. The close call added a desperate edge to her work. It seems she was driven mad with the impression she had to write, had to get it out, and so she began the tremendous period of creativity that would define her short career.

She learned that Cortázar would be coming to Montreal as part of a literary conference Hébert was organizing. “I want to meet more artists,” she told Hébert. “Introduce me to some writers, to some people more like me.” He told her she could come participate at the forum. He’d even put her at Cortázar’s table.

“It was as if they had known each other all their lives,” said Rivard Trottier. “It was instant. It didn’t even matter their age, they were exactly the same. It was two lost souls finally together.” Cortázar, who was thirty-two years older than Dunlop, stayed about a week in Montreal. He read one of her short stories, a complicated piece about reflections and death. She must have made him laugh. He the big lover; she the beautiful, fragile girl.

A few weeks later she received a letter from Paris, written in French. (As with all of their letters, no official translation exists.) Cortázar told her he hadn’t stopped thinking of her, or of her short story. He told her that in her, he saw himself. Here’s what I envision, he wrote, inviting her to come to Paris. He wanted them to write together. It all sounds a bit like a dream, but if you give dreams a little push, sometimes they can happen.

THEY SETTLED INTO their first night on the road with a glass of whiskey and the typewriters singing in near unison. The words would come easy now. “This parallel highway we’re looking for perhaps only exists in the imaginations of those who dream of it,” wrote Dunlop from her makeshift office in the passenger seat. Cortázar was in the back, his writing machine on the fold-open kitchenette counter. She read aloud to him, holding the draft between two smudgy hands, an unfiltered Gauloise dangling from her lips.

“But if it exists ... it doesn’t just involve a different physical space but also another time. Cosmonauts of the autoroute, like interplanetary travellers who observe from afar the rapid aging of those who remain subject to the laws of terrestrial time, what are we going to discover when we go at camel speed after so many trips in airplanes, subways, trains?”

“Autonauts of the Cosmoroute,” said Cortázar. “The other path, which is, in any event, the same one.”

They liked the sound of it.

WITH DEATH IN THE BACK OF HER THROAT, its terrible metallic taste chasing her everywhere she went, Cortázar’s letter inviting her to Paris must have seemed god-sent. It meant she had to leave behind her ten-year-old son, but she believed she was dying. “I think in a way, she knew she wouldn’t be there for him, and this was her way of leaving him something behind,” says Rivard Trottier. Hébert had a new girlfriend and Dunlop might have been paving the way for her replacement while at the same time creating her legacy for Stéphane.

She landed in Cortázar’s world in January 1978. She’d only go back to Quebec a handful of times, “two, maybe three, not four, and only ever for a few days,” according to her ex-husband. She wrote to Stéphane nearly every day. The letters are long and written as though they were intended for an adult. She almost always begged for Steph to write back, though he seldom did.

In the summer of 1978, Stéphane came to visit his mother and Cortázar at their writing retreat in Provence. They stayed part of the time in Cortázar’s mortar bungalow, cruising around the countryside in Fafner, and the other half at Serre, home to their friends Jean and Raquel Thiercelin. “Demons are not allowed to access Serre,” Cortázar once wrote of the ancient fortress.

That summer, Hébert played war with the Thiercelin boy. Dunlop and Cortázar planned to write a book together, but they had no idea what it would be. They took siestas, wrote a little, then drank a little in the splendid French Midi sun. “It was a true association of Cronopios,” recalled Raquel Thiercelin, serving foie gras from beneath one of the ancient house’s crumbling towers. Cronopios is Cortázar-speak for people who are beautiful, silly and timeless.

But even in the land of Cronopios, even where Cortázar was so sure the evil could not pass, the darkness found them. Dunlop fell into a coma and returned to the hospital.

Stéphane left for home, and the plan was for the couple to take Fafner back up to Paris. They would have to take their time, though; she was still so frail. The Autoroute du Soleil, with its abundance of rest stops, was perfect for the slow, steady journey home. The little parking lots on the side of the highway varied from the picturesque, with luscious green parks full of tourists, to the desolate, adorned only by naked, rectangular patches of gravel.

They made their first stop at one of the more beautiful rest areas. They parked Fafner under a patch of shade, took out their picnic chairs and set up the collapsible table. Cars whizzed past in the afternoon light. “If only we could keep going at this pace,” Dunlop said. “Like stagecoach travellers.” And just like that, they were hit with the idea for their book in two voices. They excitedly sketched out their master plan for the adventure. They would write about the highway. And somehow, they would uncover a new world.

It would be almost four years before they started the adventure. There was always a conference here, a speaking opportunity there. Dunlop had influenced Cortázar with her anti-establishment views and they had taken up the Sandinista cause in Nicaragua. (One contemporary writer friend of theirs, Mario Vargas Llosa, joked that after Dunlop landed in Paris, Cortázar grew his beard wild, bought pornographic magazines and started rattling on about revolution.) Life was simply too hectic for the big road trip.

That all changed in the summer of 1981, when Cortázar was hospitalized with a near-fatal stomach abrasion. His doctor saw something odd and ran a test. Cortázar, the doctor told Dunlop, had leukemia. “Don’t you dare tell him,” she said. “He can never know.”

“Carolita didn’t want to worry him,” said Thiercelin. He had so many novels left to write, Dunlop would confide in her letters, if he knew he was dying, he’d only fall into an inescapable hole and never create again. But after she heard the news, Dunlop pushed Cortázar to finally take that expedition on the Autoroute du Soleil. She made him promise: next spring, no matter what, we are doing it.

On May 23, 1982, a Sunday, they packed up their dragon and exited onto the A6 highway, leaving behind a gentle Parisian rain.

AT ONE POINT in Autonauts of the Cosmoroute, Cortázar spends an entire chapter dissecting the ways in which Osita sleeps. (Phase one: the heavenly, peaceful release. Phase two: the blanket thief, the scruncher-upper. Then she wakes, his “reason to live a new day.”) In another section, they relate an epic attack of the ants, when an ignorable universe comes alive under their gaze. In yet another, they take turns describing their lovemaking. Cortázar’s description is a humorous glance at the mechanics of sex in a camper van. Dunlop’s, an extended metaphor of their bodies coming together like “dolphins in a sea.”

And, somewhere near the beginning, there is Dunlop’s encounter with an angel in the washroom. It’s not fiction but you know what she is seeing is in her head. It is an ironic take on turn-of-the- century travelogues. There was no South Pole or African heart of darkness to delve into for the first time, there was no exotic end-point. It was a highway. The mysteries and the wonder were entirely in the possession of the explorers to relay, and invent, as they saw fit. As cars and trucks sped past, each on its way as fast as possible, our explorers were parked in a universe of their own making.

After thirty-three days on the autoroute, they reached their destination: Marseille. How they dreaded the signs announcing the closing in of that graffiti-littered port. There were no shouts of joy, no clamouring to the top of the mountain, when they arrived. Cortázar called it a “reverse apotheosis.”

Away from the experimental time warp of the highway, life resumed its infernal speed immediately. Within weeks they were on a jet to Nicaragua. But their book still needed to be illustrated and they had the perfect man for the job: Dunlop’s thirteen-year-old son Stéphane. Far away from the boys playing games on St. Urbain Street in Montreal, Stéphane came to live with the revolutionaries. He fired an AK47 and had his very own bodyguard. And when he wasn’t hanging out with the junta, he was combing through the manuscript of Autonauts, deciphering the adventure to draw the relief maps that would illustrate it. It was the closest he’d been with his mom in years.

One night that summer, somewhere outside Managua, their reunion was cut short. Stéphane’s memory of the night is fuzzy because of what happens next. His mother needed to get to a hospital. They sped through the jungle in an old Mercedes. Every time the car hit a bump, or swerved to stay on the muddy path, Dunlop wailed in agony. Did he have a chance to say goodbye as they rushed her to the little plane? Did Cortázar have time to tell him everything was going to be fine before they left the boy behind? Did he kiss his mom? Who remembers? They had taken her back to Paris. It was the last time he saw her.

Back in Montreal two months later, on the day before his fourteenth birthday, Stéphane came home from school with a friend who was also called Stéphane. The phone rang. The story goes that the other Stéphane picked it up. It was Cortázar on the line from a hospital in Paris. “Yes, this is Stéphane,” said the other boy, and Cortázar mistakenly gave him the news. Dunlop was dead. She was thirty-six years old.

“WE RETURNED TO PARIS FULL OF PLANS,”wrote Cortázar in the final chapter of The Autonauts of the Cosmoroute.

Finish the book together, donate the royalties to the Nicaraguan people, live, live even more intensely. There followed two months that our friends filled with affection, two months in which we surrounded la Osita with tenderness and in which she gave us each day that courage we were gradually losing. I watched her embark on her solitary journey, where I could no longer accompany her, and on the second of November, she slipped through my fingers like a trickle of water, without accepting that the demons would have the last word, she who had so defied and fought them in these pages.

“It’s too bad we are deprived of the books that would have been,” said Marie Claire Blais, a critically acclaimed French-Canadian writer. “She would be such an important writer today.” Dunlop had translated Blais’ novel Deaf to the City in the early eighties. “Carol was simply a miraculous being,” Blais says. “The fact she was always between life and death gave a sense of urgency to what she was writing. She was not a person who was resigned.”

Cortázar owed it to her to finish the book. He assembled the maps, their type-written manuscript and Osita’s handwritten ship’s log and had the book published the following year.

“I know very well, Osita, that you would have done the same if it had fallen to me to precede you in the departure, and your hand writes, along with mine, these final words in which the pain is not, never will be stronger, than the life you taught me to live ...”

Fifteen months after Dunlop, Cortázar died. They buried him next to her in Paris, beneath a large marble sculpture of an open book.

The highway in France continues its ceaseless roar—a bit of tarmac, connecting you to your destination. But those who’ve read the book peel open their eyes over an unremarkable roadway and find something else. She was the navigator. It was a new world they had found. She was showing us the way in.