Victoria Sieczka

Victoria Sieczka

Fleur de Least Resistance

Alan Randolph Jones on Those Who Make Revolution Halfway Only Dig Their Own Graves, which deconstructs the relevance of revolutionary fervour in modern-day Quebec.

During a pivotal scene in Those Who Make Revolution Halfway Only Dig Their Own Graves (Ceux qui font les révolutions à moitié n’ont fait que se creuser un tombeau), we see a candid smartphone video of the Quebec student protests in 2012. Montreal police wearing riot gear storm a wall of protesters and pull one of them down as he struggles against them. They put zip ties on his wrists and pull off his ski mask. Then, the frame widens to reveal this same young revolutionary, codename Tumulto (played by Laurent Bélanger), safely in the confines of a dark, dingy apartment, wistfully watching himself get arrested on YouTube. When his comrade, codename Ordine Nuovo (Emmanuelle Lussier Martinez), walks into the room and accuses him of being nostalgic, which is a crime in times of “war,” Tumulto is forced to stand naked before his comrades and plead guilty of “being lulled by the comforting and numbing sweetness of [his] past.” He beats his own face until his judges, three disillusioned young people like himself, are satisfied that he has learned from his mistake.

Revolution is a radical film, in both the political and formal senses of the word. Its runtime rivals the length of its title, clocking in at three hours and three minutes, including an intermission scored by black metal; it combines scripted narrative with archival interviews of Québécois intellectuals, smartphone-captured footage of the 2012 Quebec student protests, performance art set pieces and voiceover narration of Marxist and revolutionary political texts, everything from Rosa Luxemburg to Pierre Vallières.

Revolution is also distinctly, unapologetically Québécois. It’s a far cry from the easily exportable Québécois films of recent years that have dominated festival coverage and earned Academy Award nominations, like the genteel drama Monsieur Lazhar or the globetrotting thriller Incendies. Drawing influence from Jean-Luc Godard’s “Maoist” period and the kind of formally abrasive, politically radical tracts he made with the Dziga Vertov Group in the late sixties and early seventies, Revolution exhibits no desire to be liked. A friend of mine reported that it inspired walkouts at a Toronto International Film Festival screening even as it won the festival’s top Canadian film honours. (Given the content and style of the film, one might have expected the filmmakers to reject the prize as a critique of imperialist anglophone hegemony or the festival’s excessive corporate sponsorship.)

The protagonists of Revolution form part of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Quebec (AFQ)—a fictional, post-Maple Spring terrorist cell modelled after the militant separatist group Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). (For those who didn’t witness the events unfold on the news or learn about them in history class, the FLQ committed a series of bombings throughout the 1960s before their actions culminated in the 1970 October Crisis, when two cells kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross and Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte, eventually killing the latter.)

The AFQ cell at the centre of the film consists of four codenamed individuals. Along with Tumulto and Ordine Nuova, we have Giutizia (Charlotte Aubin). These three are socially alienated young people from middle-class backgrounds, but the fourth member of the cell is Klas Batalo (Gabrielle Tremblay), a transgender sex worker who foots the bill for her unemployed, university-educated comrades. Together, this group of disaffected youth live in a dilapidated apartment, reading Peter Kropotkin and proselytizing to each other about the coming revolution.

Despite their stated convictions, the spectre of nostalgia weighs heavily on these characters. Not just nostalgia for the 2012 protests, which gave Tumulto’s violent impulses meaning, but also for Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, when radical change seemed not only possible, but imminent.

When they can afford to, Revolution’s four would-be revolutionaries commit small, symbolic acts of terror, sticking to pre-9/11, Marxist kind of stuff: tossing Molotov cocktails at gentrifying storefronts, mailing envelopes of Anthrax-resembling flour to political offices, painting over highway billboards with revolutionary slogans.

For the most part, though, these characters mope around, depressed and despondent. Unlike the real-life members of the FLQ, who came from working class backgrounds, our modern-day militants seem motivated more by middle-class ennui than actual oppression. Though the film doesn’t shy away from showing us the authoritarian nature of the police or the hyper-commercialization of downtown Montreal, it also contrasts its characters’ rhetoric against shots of young people picnicking in Parc La Fontaine and shopping on St. Catherine Street, apathetic to any kind of radical plight.

In one scene, Batalo reclines in a chair for a bikini wax, chatting with her Chinese-Canadian aesthetician in English. In Quebec, English has often acted as a colonial threat to Québécois culture, but here it is the language that Batalo’s aesthetician uses to explain how her family ran “from starvation and the dictators” to immigrate to Canada. When the aesthetician confesses to Batalo that she doesn’t understand why Quebec would want to separate from Canada, Batalo doesn’t have an answer, and the moment illustrates the difference between the political alienation of these young people and the very real oppression faced by people across the world. Moments later, though, the aesthetician shifts the conversation to Batalo’s gender identity, and we’re reminded of the various intersecting ways that oppression works.

Watching Revolution in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory and the rise of far-right parties in Europe, radical political action has a renewed urgency and appeal, but the decayed remains of an ethnocentric revolutionary movement seem ill-equipped to deal with both the ethnically diverse population of contemporary Quebec and the problems of the contemporary world.

Revolution is the second film by Mathieu Denis and Simon Lavoie to explore the fractured, paralyzed remains of Quebec’s revolutionary moment in contemporary Montreal. Their previous film together, 2011’s Laurentia (Laurentie), follows a young francophone man, Louis (Emmanuel Schwartz), as he moves from his small town to bilingual Montreal and faces a subsequent crisis of identity. The title, Laurentie, was used by followers of priest and nationalist Lionel Groulx in the 1930s to refer to the name of a proposed Catholic French-Canadian state. In one scene, Louis visits a church, hoping to make sense of his confusion and loneliness, only to find himself surrounded by the fragmented, grey-haired remains of Groulx’s Quebec, which has been ravaged by the secular nationalism of the late twentieth century. By the time Louis arrives at this part of his heritage, its proffered feelings of community and belonging have been replaced by fatigue.

That scene is helpful when parsing the sentence-length title of Those Who Make Revolution Halfway Only Dig Their Own Graves. At first glance, the “halfway-made revolution” seems to refer to the Maple Spring, which shut down Montreal streets for almost four months in the spring of 2012. Though it is sometimes credited with bringing down the Liberal government of Jean Charest, five years later the Maple Spring seems close to forgotten, and the idea that it may have spawned a radical Marxist terrorist cell seems quaint, like a relic from another generation. Just as Groulx’s Catholic utopia was pushed out of the way for René Lévesque’s secular vision of an independent Quebec, leaving only fragments of a potential Laurentie in the twenty-first century, so does the radical indépendentiste vision of the 1960s find itself out of time and out of place in the 2010s.

It seems likely, then, that Those Who Make Revolution Halfway Only Dig Their Own Graves also refers to the Quiet Revolution and the grave that it dug for the promise of true sovereignty. Young people from that era appear as bourgeois baby boomers in Revolution, such as a wistful client of Batalo’s who recalls his own youth as a burgeoning revolutionary. “I tried, you know?” he tells her. “But at some point you get old, you get scared, you have to work, earn some money.”

Early in Revolution, Denis and Lavoie incorporate an archival CBC interview with Hubert Aquin, which plays over footage of Ordine Nuovo entering a Montreal metro station and throwing a smoke bomb. Aquin was a Québécois novelist and revolutionary who was arrested in connection with terrorist activities in 1964. Four years after the October Crisis and the peak of revolutionary sentiment in the province, the interviewer asks him about an article he wrote on Quebec’s “cultural fatigue.” Aquin says, “I was writing in a sort of pre-revolutionary period, and there has been no revolution after that... [the revolution] may come, it is probably always about to come.” But forty years have passed and no revolution has arrived. Aquin took his own life in 1977, leaving a note that read “I have lived intensely, and now it is over”—a sentiment that could easily act as a eulogy for Quebec’s short-lived militant fervour.

Unlike Aquin, many Quiet Revolution-era sovereigntists simply became a part of the bourgeois middle-class when public sympathy dissipated for militant resistance. Denys Arcand’s 1981 documentary Comfort and Indifference blamed these apathetic middle-class Quebeckers for the failure of the 1980 sovereignty referendum; he felt they’d been coerced into voting “No” out of fear of rising gas prices and other economic anxieties.

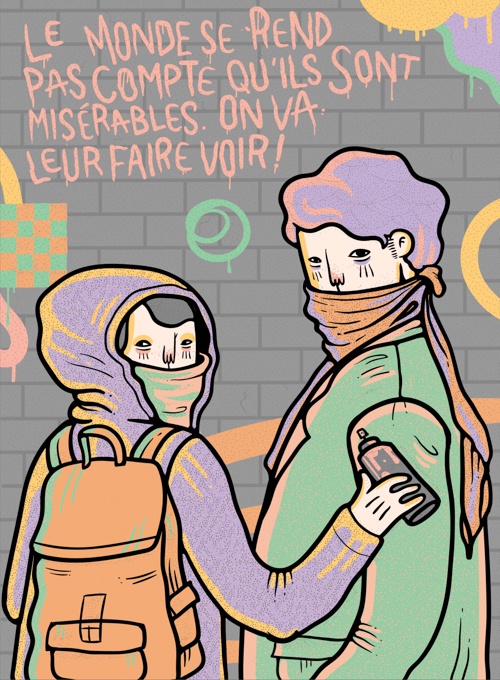

Revolution acts as a critique of nostalgia for Aquin’s “pre-revolutionary” moment. Nostalgia is against the rules for Revolution’s characters, but every one of their actions is dictated by longing for a time when militant radicalism truly threatened the status quo. Further, the Quebec of the film, much like the Quebec of today, is a place where consumerist desires will always trump idealism. In the opening scene, Tumulto, Giutizia, Nuovo and Batalo paint over some billboards near the Jacques Cartier Bridge that advertise cars and smartphones. Their message reads, “People do not yet see they are miserable. We will show them!” One of the billboards they paint over, however, already read “Revolutionary.” It is an ironic and revealing moment: if the language of Marxism has long been co-opted to sell consumer products, the nostalgia for revolutions past cannot be the way forward.