Sean Lewis

Sean Lewis

Tall Tales from the Underground

An urban myth holds that Portland’s subterranean tunnels were used to kidnap sailors for cheap labour. Will Preston digs into the story’s facts and fictions.

A few blocks west of the Willamette River in Portland, near an intersection lined with nightclubs and maple trees, lies an unremarkable metal hatch in the sidewalk. At first glance, it looks like a manhole cover or electrical panel. If you pry it open, however, you’ll discover an ancient set of narrow wooden stairs—so narrow you have to turn your feet sideways to descend—leading down to a dirt floor, a few bare bulbs, walls built from huge slabs of stone, and a hallway leading off into the darkness.

Built in the late 1800s and long since abandoned, the Portland Underground once comprised a vast network of basements, corridors and tunnels that sprawled below the streets of downtown. As much of it remains unmapped and unexplored, its true extent is unknown; some claim it stretches for miles, and that hidden entrances remain scattered across the city as trapdoors in the floorboards of old bars and movie theatres.

Most notably, the underground is rumoured to have been the nexus of a nineteenth-century human smuggling operation known as Shanghaiing. According to this theory, Portland was plagued by an unacknowledged epidemic of kidnappings from the 1850s to the early 1900s: thousands of men were snatched right off the street during peak years, spirited away through the tunnels and used as slave labour on board the ships departing Portland’s harbour. According to legend, these men wound up as far away as Shanghai. This story, published in histories of the city, newspaper articles and travel guides, has become so entrenched in Portland’s consciousness that it’s endowed the underground with a second name: the Shanghai Tunnels.

The man behind this theory is Michael Jones, a local historian who first discovered the underground as a boy. Jones has spent more time researching and excavating the tunnels than arguably anyone else alive. He’s collected troves of local oral histories; he is the director of the nonprofit Cascade Geographic Society; he founded a museum dedicated to the tunnels; he’s dug out large swathes of the ruined tunnels himself, by hand. His tours of the underground have run since 1992 and he says they attract more than eight thousand people annually. Jones once even moved into an empty storefront after hearing rumours it possessed a trapdoor.

But over the last decade, Jones—and the underground itself—have become mired in controversy. According to a growing number of local scholars, there is no secret network. There were no kidnapped men. And above all, there are no Shanghai Tunnels.

I met Jones in Chinatown last May for a tour. He said he had just come from a meeting with a TV executive about filming a new show in the underground, though he wouldn’t tell me which show. “That’s still confidential,” he said.

The tunnels are infamous for being one of the most haunted spots in the nation. They’ve been featured on various “documentary” television shows, many of which—Ghost Adventures, Ghost Mine, Ghost Hunters International—have the word “ghost” in the title. But as Jones lifted up the metal hatch and stepped carefully down the stairs, he assured me he didn’t believe in ghosts. “This isn’t Disneyland,” he said dryly. “Nothing’s gonna jump out at you.” Still, he wasn’t above sprinkling his narrative with hints of the supernatural. He spoke of chasing shadows into empty rooms, something tugging at his shirtsleeve. Strange whistling in the dark. Cigar smoke.

Jones looked the part, too, like a character out of a Robert Louis Stevenson novel. He shuffled slowly, propped up by a thick, gnarled cane. Stringy grey hair draped down both sides of his face. One of his eyes didn’t quite focus, giving the impression that he was looking both at you and past you at the same time, seer-like. We paused at the bottom of the stairs, pulled two flashlights from a wooden box and followed their beams into the darkness below the city.

Low-hanging pipes and wooden beams criss-crossed the ceiling, forcing us to hunch and duck as we walked. I had expected the tunnels to be eerily, unsettlingly quiet. But the passageway burrowed directly under a local restaurant and piano lounge, and above my head I could hear hurried footsteps, chairs scraping, muffled exchanges. A dampened piano melody wove through the din: “The Girl from Ipanema.” We moved invisibly beneath it all, parallel to the surface world.

The hallway eventually fed into a cavernous room, empty save for a few dusty artifacts pushed up against the wall—wooden chairs, a carriage wheel, a flour bin with roses painted on the side. I swung my flashlight around, searching for ghosts or another hallway, but saw only stone and sand and washed-out brick, everything the colour of a tombstone. One wall featured a gigantic hole, and Jones motioned me towards it before ducking through. I followed him into another basement as stark and barren as the first. Jones stood in the corner, an exposed lightbulb flickering above him. “This is where it all happened,” Jones told me. Then he reached up and pulled the cord, and the room dropped into darkness.

Nineteenth-century Portland was a far cry from today’s clean, vegan-friendly metropolis. Perched on the banks of a temperamental river, it was a port city that flooded frequently and stank with “the odours of fish, soap, sawdust… and polluted, smoke-filled air,” according to author Jane Comerford. Founded in 1851, the city quickly gained a reputation for lasciviousness. By the late 1800s, it was teeming with brothels, taverns and gambling houses, often all three in one. Corruption was rampant; as Jones quips, “we had plenty of police, but no law enforcement.”

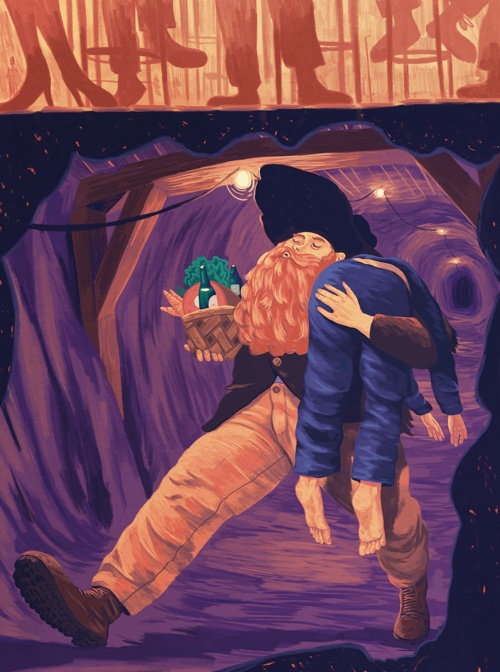

At the centre of it all were the Shanghaiers. According to Jones, ruthless, manipulative and greedy men like Jim Turk and Joe “Bunco” Kelly were in the lucrative business of rounding up crews for long, punishing voyages leaving Portland’s harbour. Where possible, Turk and Kelly and their brethren nabbed rogue sailors. But the headhunters also often preyed on ordinary men drinking in bars by drugging them, plunging them through trapdoors and carting them away—sometimes in wheelbarrows—to the waterfront. Jones claims that, on average, over 1,500 men were kidnapped annually from 1870 to 1917, with the Shanghaiers pocketing a handsome finder’s fee for each one. Most were never heard from again.

Jones has staked his career on this story, which he claims is assembled from the accounts and recollections of local old-timers. “This truly is an oral history,” he told me, as shadowy cabals don’t usually leave ledgers of their misdeeds lying around. Jones had heard testimonies from policemen who had raided the tunnels, relatives of the vanished, even an elderly victim who had escaped and managed to make his way back to Portland. The man, held captive in the underground, had led Jones to the very room we were now standing in, where the alleged former prisoner pressed his hand to the wall and burst into tears.

Jones motioned towards a stone wall with barred windows peering out into nothingness. He explained there had once been cells here, secured to the wall, the dimensions of an outhouse or a coffin turned on end. For insurance, the Shanghaiers confiscated the prisoners’ shoes and scattered broken glass across the floor. The cells were dismantled by the fire marshal in the 1970s.

“But…” Jones shone his light on the floor behind me.

The shoes were still here. Eight or nine pairs in an unruly heap: work boots and loafers, blanched from years of darkness and coated with a thick layer of dust. The shoes were Jones’ smoking gun. He had moved them into a wooden box to prevent damage, but otherwise, he said, “they’re just as we found them.”

That isn’t the case for much of the underground. Huge sections were filled in by the urban renewal projects of the late 1950s, which revitalized Portland’s withering downtown but also scattered long-time residents, destroyed historic buildings, and drove up property prices. Development of the city’s light rail system in the 1980s caused similar destruction. Now the city is earthquake-proofing, reinforcing foundations and developing a policy to fill in the cavities beneath at-risk buildings. Jones believes that by beautifying itself, the city is whitewashing its past. “We’re moving beyond our roots. And that’s not a good thing for a society to do,” Jones says. “They’re trying to silence me because it makes Portland look bad.”

Jones is not as paranoid as it seems. Oregon has, of late, seen an unprecedented population boom—more people moved here in 2015 than any other state—and it also has a bad habit of downplaying aspects that may tarnish its image as a liberal Shangri-La. Its original constitution, for example, actually forbade African Americans from living here, a law that remained in effect until 1926. (Even today, under 3 percent of Oregon’s population is Black.) In Portland, the homeless population has risen by 30 percent in the last eight years. These are issues you won’t hear mentioned on Portlandia.

Still, Jones’ complete reliance on oral history is one of the primary criticisms levelled against his research, especially since many of his artifacts (trapdoors, wooden cells) are either circumstantial or missing. Oral accounts, of course, can be valuable and even essential, as in the case of Indigenous histories. But most Western cultures lack a strong oral tradition. And as human memory is so susceptible to time and suggestion, historians generally agree that spoken accounts are best used to corroborate written ones.

Jones argues that this attitude is wrong. As he sees it, state historians are only interested in a preordained narrative, and they’re ready to dismiss anything that contradicts it. Jones equates this with censorship. The answers, he insists, lie with the common people. “You meet them, you gain their trust, and they start showing you things. Telling you where to go. I’ve rarely gotten bad information. But you have to rely on oral history.” You set a dangerous precedent otherwise, he says. A lack of clear evidence doesn’t mean a crime didn’t occur.

“It’s the Bigfoot argument,” Doug Kenck-Crispin told me. “Just because there’s no proof of Bigfoot doesn’t mean there’s no Bigfoot.”

We were sitting in the Dan & Louis Oyster Bar, a short walk from where I had met Jones. Founded in 1919, Dan & Louis is one of the oldest bars in the city, and one of the few buildings with a visible link to the underground. Just a few feet away from us, a heavy pane of glass revealed a burrowed-out hole dropping some twenty feet down. At the bottom, a human skeleton reposed against the wall.

Kenck-Crispin is one of several local historians who has worked to debunk the Shanghai Tunnels story, which had gone largely unchallenged until a 2007 article in the Oregonian raised doubts about its veracity. An easygoing guy with thick-rimmed glasses and a mosaic of tattoos up his arm, Kenck-Crispin is the resident historian for the podcast Kick Ass Oregon History (KAOH); he’s researched everything from Portland’s first Black police chief to a history of cow attacks in the state. Several years ago, Kenck-Crispin turned his attention to the Portland Underground. He spent months digging through newspapers and historical records and aired his findings in a special, two-part KAOH episode. It was titled, succinctly, “The Shanghai Tunnels are Bullshit.”

“I haven’t seen anything,” Kenck-Crispin said. “Not one shred to indicate that this really happened.” It wasn’t just Jones’ reliance on oral history that troubled him. Jones has also refused to release any of his research: interviews, supporting documentation, even the names of people he’s tracked down. “I’m not willing to discount oral history by any stretch of the imagination,” Kenck-Crispin said. Usually, though, there’s some written testimony to back it up, especially if there are “ten or twelve or fifteen [accounts] that told the same thing.” In this case, there was nothing—not a single reference to tunnels in all the accounts of Shanghaiing he’d read. He acknowledged it was possible that Jones’ sources were accurate. But, Kenck-Crispin said, “they’re behind this sealed door. What facts add up, what facts don’t? You’ve got this evidence you’ve been sitting on for forty years. Why not bring these Shanghai Tunnel stories out of the dark?”

Jones, of course, is suspicious of such requests, seeing them as thinly veiled excuses to attack—or steal—his work. Jones claims to be funnelling his research into a book, but he’s been saying that for ten years now. In conversation, he was cagey, referring to a cache of “articles and documents” he had recently discovered in a “town that has nothing to do with Portland.” But he refused to divulge anything more—not what the documents contained, not even the name of the town. “I’ll keep it quiet,” he said, eyeing me as though I might be a spy.

To other historians, there’s a simpler explanation for why none of Jones’ research has surfaced: it doesn’t exist. Shanghaiing, as Barney Blalock points out in his definitive book on the subject, The Oregon Shanghaiers, was actually a common practice, not only in Portland but also San Francisco, Seattle and Vancouver, to name a few. Shanghaiers—also known as crimps—ran boarding houses along the waterfront, and enticed sailors by promising to find them “a better ship with higher pay.” It was all a scam, of course. Leapfrogging from ship to ship was desertion, which meant the sailors forfeited their wages. Penniless, they paid the crimp for the room with advance earnings from the new ship—which they would most likely desert again at the next port. The crimps got rich. The captains got free labour. And the sailors, moving “from port to port… [without] a dime to call [their] own,” got screwed.

In other words, there was no need for a secret network. No trapdoors, no kidnapping. And the closer you look at Jones’ story, the more unlikely it seems. Blalock, who worked on the Portland waterfront for thirty years, points out that until 1900, the Willamette River was far too shallow—only five feet deep in places—for ocean-going ships, and that they were left in Astoria, 113 miles downriver, while sailors travelled to Portland in steamboats. Other questions remain: even if there were tunnels that connected to the waterfront, what happened when the river flooded? And given that Shanghaiing ended around 1908, who is still alive for Jones to talk to?

The consensus is clear. Until and unless Jones releases his book, and his research can be vetted, the story of the Shanghai Tunnels looks to be just that: a story, an urban legend run wild. As Blalock puts it, it likely has as much historical truth as the Pirates of the Caribbean.

Despite the controversies, interest in Jones’ tours has only escalated in recent years, and many Portlanders still embrace his story as gospel. In part, this may be because no one seems able to agree on what the underground was actually used for. Across multiple interviews, the theories I heard included: storing goods, transporting goods, opium dens, homeless dens, Chinese gaming parlours, Chinese gang wars, brothels, illegal boxing rings, union meeting halls, company meeting halls (after they kicked out the unions), Polynesian burial sites, transit for disabled people and human waste disposal. Some asserted that the “tunnels” were nothing more than a series of interconnected shop basements, filled with dry goods and shipping materials. No two people gave the same answer.

Chet Orloff, a professor in urban studies at Portland State University and the former director of the Oregon Historical Society, presumes that the underground had a fairly pedestrian purpose: moving goods from one spot to another in a city with cobblestone streets and two hundred days of rain a year. Portland, he says, is “hardly unique” when it comes to tunnels. Nearly every major North American city has a tunnel system of some sort: New York, Seattle, Toronto, Edmonton, Ottawa. In Chicago, he says, “they even went so far as to build a little train system underneath.”

Still, we as humans are drawn to things we can’t quite see, and our fascination with tunnels and their suggestion of conspiracy remains alive and well, even in the face of decisive evidence to the contrary. Even Orloff isn’t willing to completely discount the value of the Shanghai Tunnels narrative. It likely started as a bogeyman story, he says, a way for parents to scare their kids away from a dangerous part of town. But “the very fact that [Shanghaiing] would’ve been used as a scare story… [is] enough to suggest, well, there may be a grain of truth in it.”

And a grain is all we need. “People like to believe their community has interesting origin myths,” Orloff says. “People are natural storytellers. We go to great lengths to convince ourselves that a story is real.” While Orloff cites UFOs, and Sasquatch, as Doug Kenck-Crispin had, he also seems more sympathetic. “Stories help define us,” he says. “They give us colour, things to talk about, things to share. They confirm and convey, hand down facts or events.” We tell the stories we feel reflect our identity—and by extension, the identity of our place and our community. Without them, what do we know of ourselves?

On a bright spring evening, I walked past the hatch where Michael Jones and I had disappeared beneath the sidewalk, and I remembered what he’d told me about Portland whitewashing its past. “We had to go through that maze of difficulties,” Jones said. “Good things and bad things. That’s all part of it.” To now absolve the city of its tumultuous history would be to rob it of its character, its individuality.

I waited for the light to change on the corner of Burnside and NW Third Avenue. Across the street, a giant mural in block yellow letters read KEEP PORTLAND WEIRD. To the east, a new twenty-one storey apartment building loomed in the skyline, black and angular, referred to locally as the Death Star. Eleven towers like it were planned in downtown. Rent was skyrocketing; lifelong Portlanders were moving away. The city seemed to be vanishing before our eyes. I wondered if anything would remain of the underground when it was all over. I wondered what stories, true or not, we would have left to tell in its place.