Myfanwy MacLeod, The Butcher’s Apron (2017).

Myfanwy MacLeod, The Butcher’s Apron (2017).

Photos Worth a Thousand Houses

Vancouver photography rises and falls with Vancouver real estate—for better and worse.

The setting for Jeff Wall’s 1986 photograph, The Storyteller, one of the most famous works of art to ever depict Vancouver, is slated for demolition. The Storyteller depicts six First Nations people camped on a slope beside the Georgia Viaduct. The scene is unglamorous: the subjects occupy a patchy grass knoll, flanked by tall evergreens on the left and the overpass on the right. A pair of electric cables, used to power the city’s trolley buses, is suspended from the underside of the overpass and runs perpendicular to it, bisecting the image and visually separating the knoll from the commuter thoroughfare above. More than two metres by four metres, the photograph is displayed in a billboard-like format, printed in colour on a transparency and mounted in a lightbox. Its backlit glow clashes with the people it represents, on the margins of a crossing between two kinds of transportation—one public, the other private.

The Storyteller also invokes municipal history. The Georgia Viaduct was originally constructed in 1972 as an entryway to a proposed freeway system that would have destroyed Vancouver’s Chinatown, Gastown and Strathcona neighbourhoods. Massive public demonstrations halted the project. For over thirty years, Wall’s photograph has stood for a battle between the city’s expansionist ambitions, here thwarted, and the different constituencies of citizens whose neighbourhoods this so-called growth would demolish.

In Vancouver, art and real estate are never far apart. The Storyteller coincided with Expo 86, the catalyst for both Vancouver’s branding as a major world city and the unprecedented acceleration of its housing market. Today, the photograph, which according to art critic Barry Schwabsky “might be best of Wall’s earlier works,” is part of the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Meanwhile, Vancouver has eclipsed Manhattan as North America’s most unaffordable housing market, and the Georgia Viaduct will soon be replaced by yet more condos.

Vancouver’s international stature and that of its art rose in tandem after 1986. In the nineties, as Vancouver began to regularly appear in “most livable cities” lists, Stan Douglas, Ken Lum, Jeff Wall and a handful of the city’s other artists gained global renown. They were lumped together under the moniker of Vancouver photo-conceptualism, or sometimes simply the Vancouver School. Known for combining the outsized ambitions of cinema and eighteenth-century history painting with the new format of large-scale photography, the photo-conceptualists also dispensed with local tradition by focusing their attention away from Emily Carr-type wilderness landscapes and towards their urban environment. Another Objectivity, a 1989 traveling European exhibition that popularized large-scale photography, forecasted Wall as one of the twelve photographers to watch in the nineties. In their essay for the exhibition’s catalogue, curators Jean-François Chevrier and James Lingwood also singled out Vancouver photographers’ sophisticated engagement with their city for praise. Solo exhibitions in Europe and the United States and representation by blue-chip galleries in Cologne and New York (then capitals of the international art world) soon followed for Douglas and Lum.

By 2005, two years after the city was awarded the 2010 Winter Olympics, Vancouver art’s international reputation merited a large survey exhibition in Europe, the Museum for Contemporary Art in Antwerp’s Intertidal: Vancouver Art & Artists. Predictably, it was dominated by photography. In the wake of photo-conceptualism’s global triumph, photography came to overshadow all other kinds of art in museum exhibitions of Vancouver art. As such, the history of Vancouver art came to be told as a history of photographers. At the same time, these photographers’ images of Vancouver—especially those depicting the seventies and eighties—were increasingly used in survey exhibitions to tell the story of a city whose urban environment had changed almost beyond recognition in the intervening years. This two-sided phenomenon is best described as Vancouver photohistory.

Last summer, the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG) and the Morris and Helen Belkin Gallery at the University of British Columbia—two of the city’s largest art institutions—hosted competing Vancouver photohistory exhibitions. The usual names were well-represented in both exhibitions: in the VAG’s Pictures from Here, Douglas and Wall were joined by photo-conceptualists Roy Arden, Marian Penner Bancroft, Rodney Graham, Arni Haraldsson and Ian Wallace, while the Belkin’s Sites of Assembly featured Arden, Bancroft, Lum and Wallace.

Both exhibitions also, crucially, updated the usual photohistory narrative to raise questions about the visibility of Indigenous people in the city’s public spaces, which of course exist on the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. But those questions—posed, significantly, in works by First Nations artists—were overwhelmed by another anxiety about space, one that seemingly underpins every aspect of Vancouver and its art world: the city’s ongoing housing crisis. The average price of a detached home in Vancouver is over $2.6 million, the city’s rental vacancy rate hovers under 1 percent, and its average market rental rate has increased by a whopping 75 percent since 2001.

During the VAG and Belkin photohistory exhibitions’ runs, two works of art about real estate could also be seen around the city. Model Suite (Sliding Door), a translucent photographic mural by Vikky Alexander, depicted a model apartment suite whose glass, sliding balcony doors were outfitted with photographs staging a real high-rise’s waterfront harbour view. The photograph was installed on the windows of the entrance to the Yaletown-Roundhouse station on the Canada Line, which was built for the Olympics. Lum’s Vancouver Especially, on view indefinitely in a twenty-five-foot-wide outdoor lot between buildings in Chinatown, is a 1:3 scale replica of a Vancouver home in the mass-produced “Vancouver Special” style that took over the city in the seventies. Lum determined the replica’s size by what he could afford to produce with the work’s $45,000 budget—the approximate value of a Vancouver Special in the seventies. A month after the VAG and Belkin exhibitions closed, the BAF Gallery opened an exhibition by Emily Neufeld that paid tribute to houses slated for demolition.

More than serving as the impetus for much Vancouver art, the housing crisis has also deeply affected the very shape of art in the city. While the real estate crunch has decimated Vancouver’s live music community—leaving few venues where emerging artists can perform—it has done the opposite to the city’s non-commercial galleries and artist-run centres, a milieu that once nursed the early careers of Douglas, Lum and company. In these mostly space-poor venues, traditional physical exhibitions have been largely eclipsed by live events. Performances, lectures, film screenings, symposia and, increasingly, reading groups purportedly supplement the small-scale exhibitions in these cramped spaces, but now often seem to be the real show. Meanwhile, new exhibition-oriented, multi-gallery art spaces have opened in neighbouring municipalities—the New Media Gallery, established in 2014 in New Westminster, and Griffin Art Projects, established in 2015 in North Vancouver.

The Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver can also be counted among these new spaces. Formerly known as the Presentation House Gallery, a venerable and long-running gallery devoted to photography, it recently relocated to a $20 million waterfront home in Lonsdale Quay after receiving $4 million in seed funding from Michael Audain, founder of the real estate development company Polygon Homes.

The Polygon opened in November of 2017 with an exhibition called N. Vancouver, which, in its own words, “pays tribute to the evolution of North Vancouver, from its earliest known history as a Coast Salish village through its industrial growth in lumber and shipbuilding to its emergence as a gateway for leisure industries devoted to its mountain settings.” Closely following the VAG’s Pictures from Here and the Belkin’s Sites of Assembly, N. Vancouver features carefully chosen photographs set in North Vancouver by Douglas, Graham, Wall and other Vancouver luminaries. In situating itself across the water, the exhibition also shows us something of Vancouver anew. Just over a decade ago, Vancouver’s other most prominent developer-patron, “condo king” Bob Rennie, coined the slogan “Be bold or move to suburbia” to sell units in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Vancouver now thoroughly densified, we find ourselves—and photohistory—knocking on North Vancouver’s suburban door.

A scale model of HMS Discovery, the ship captained by George Vancouver to the Pacific Northwest in 1792, sits in the lobby of the Polygon directly to the left of the gallery’s front desk. While the sculpture is not a photograph, its installation plays on Vancouver’s well-known photogenic charms. As the first work to greet visitors entering the Polygon, the vessel appears to join the docked container ships in the foreground of the view through the facility’s floor-to-ceiling windows. Behind them lies downtown Vancouver’s north-facing harbourfront. Artist Myfanwy MacLeod chose not to represent the ship in its guise as an agent of settler colonialism; instead, she depicted its nineteenth-century afterlife as a decommissioned and permanently moored London prison boat. Charred to ominous black and dubbed The Butcher’s Apron, this dark contrast to the facility’s multi-million dollar view introduces the Polygon as yet another arena for Vancouver’s perpetual battle over space.

The Polygon’s stunning view, backed by Vancouver’s famous skyline, gives us a familiar view of Vancouver, but from the opposite perspective of the usual Vancouver tourism board or lifestyle magazine photograph. The missing mountains (and Burrard Inlet’s industrial port, which replaces the yacht-lined marinas in the south-facing False Creek) remind us that while we are looking at Vancouver, we are not in it—no independent art gallery in Vancouver has this much space.

A production still from Jeremy Shaw’s Best Minds Part One (2007).

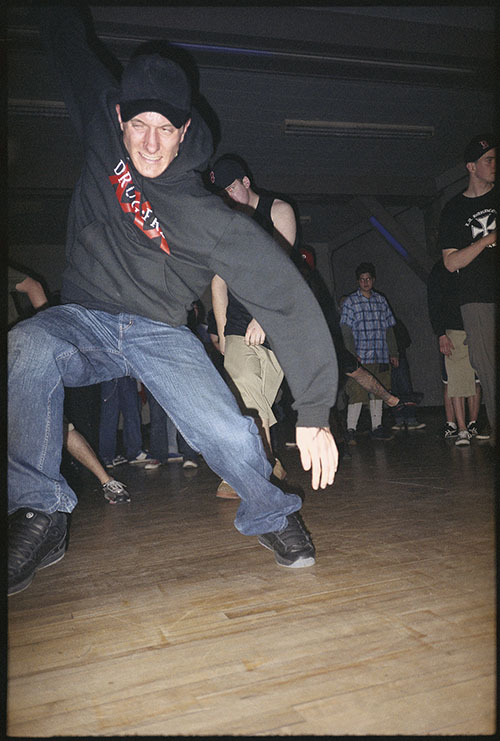

Occupying the entirety of one section of the gallery, Jeremy Shaw’s 2007 work Best Minds is the exhibition’s centrepiece. Shaw, the 2016 recipient of Canada’s prestigious Sobey Art Award, is the only artist in N. Vancouver who was born and raised in North Vancouver. Like many of the exhibition’s other works, Best Minds also takes place in North Van. The two-channel video installation, projected on large screens, features footage shot by North Vancouver-raised photographer Dan Siney of the audience at a straight-edge hardcore punk show at the all-ages venue Seylynn Hall.

Shaw slows Siney’s footage down considerably, making the slam-dancing teenagers appear to move with balletic grace. The scenario becomes dreamy: the hardcore music is replaced by a hypnotic soundtrack of ambient music composed by Shaw, and the exaggeratedly slow, handheld video image, blown up to cinematic scale, develops an almost-kaleidoscopic, soft, pixelated grain.

The crux of Best Minds is to recreate the sober but nonetheless transcendent experience of the straight-edge, hardcore circle pit. In Shaw’s hands, the hardcore breakdown—the half-time swell near the end of a hardcore song that erupts back to speedy sonic chaos and frantic slam dancing—feels like an out-of-body experience. Stretched out to a forty-minute video on an infinite loop, the shortness of the breakdown, the briefness of a teenager’s “straight-edge phase,” the smallness of an all-ages DIY show and the minorness of suburban punk scene politics are all magnified to the epic scale at which these concert-goers experience it.

Best Minds best exemplifies the ambitions of N. Vancouver, as well as those of the Polygon. Seylynn Hall, where Siney shot his footage, existed as a venue between 1996 and 2009. Originally spearheaded by enterprising teenagers, the project has sporadically been resuscitated by new waves of music- and community-hungry kids. This is the kind of thing that can no longer happen—at least not legally—in Vancouver, where significant capital is needed to secure the space needed to stage live music. Moreover, expensive condos have sprouted in every nook, cranny and alley, and strata councils would never allow the noise.

“Artwashing,” a shorthand that describes the use of art as a tool of gentrification, abounds in Vancouver art world conversations. Last autumn, Vancouver artists circulated an open letter to protest an art exhibition staged by developer Westbank Corp. “Westbank is not a cultural producer. Gentrification is not an art practice,” the letter declares. “The imperial developer ‘aesthetic,’ [which] treats housing as an elite commodity rather than a right, is an insult to the notion of art itself.” But herein lies one of the contradictions of Vancouver’s real estate-savvy art world: its emerging artists, largely critical of development-initiated displacement and almost uniformly vulnerable to the housing crisis, have built up their careers in buildings named after developers. Polygon benefactor Michael Audain’s name graces the studio art building at UBC and a gallery at Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts, while the gallery at Emily Carr University of Art and Design’s new campus is named after the late Libby Leshgold, whose family founded Reliance Properties.

Perhaps unintentionally, Vikky Alexander’s Model Suite photographs suggest that the veritable genre of Vancouver real estate critique art might be self-defeating. Her clever and artful staging of the disconnect between the photogenic Vancouver we see in films and television and the real one where people struggle to live is not an example of artwashing per se, nor is it directly a comment on artwashing, but it is difficult to tell the difference sometimes. Similarly, when the Georgia Viaduct is gone, all we’ll have left to remember it by is Jeff Wall’s photograph. As much as they track a history of displacement, Vancouver photohistory exhibitions also threaten to normalize the city’s changes—and its developer culture—as a matter of due course.

It’s ironic that a city whose institutions are so relentlessly self-mythologizing about its municipal art history would need to step outside of itself, even if just slightly to the north shore, to see itself anew. But in showing us something unfamiliar in the photohistory exhibition format, using the language of its grand sweep to highlight some of North Vancouver’s minor histories, N. Vancouver unsettles its seeming inevitability.