Is Ralph Nader Antidemocratic?

The tireless advocate's new novel is called "Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us!" Has Nader abandoned activism for enlightened dictatorship?

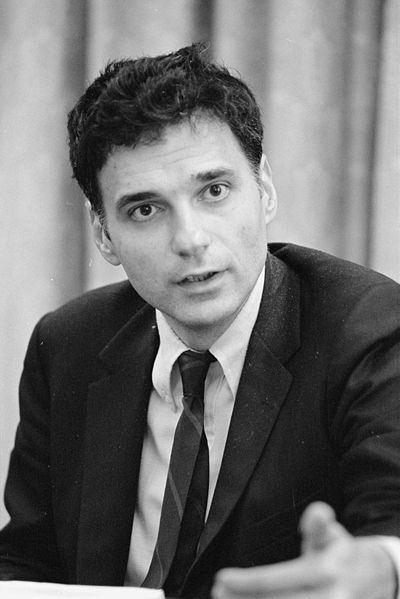

Bright yellow, 733 pages long, and entirely made up, Ralph Nader's new book is not his usual fare. Four decades in the public eye have involved the high-profile activist and consumer-rights advocate in over two dozen publishing ventures, but never fiction. That wasn’t, however, why the response at the Canadian stop on his autumn book tour was ambivalent, even mixed. Nor was it because members of the Economic Club of Canada, which hosted the swanky Toronto luncheon where he spoke, are particularly conservative. When Nader’s lecture ended and we turned our attention to the entrees, I asked the suit on my right what he thought. "It's antidemocratic," he huffed.

The novel is called “Only The Super-Rich Can Save Us!” The wry quotation marks and exclamation point are included in the title, but they do little to temper its controversial impact. No one at my table had yet read the book, and everyone thought Nader was a great guy, but some of us were uneasy. People listen to Nader because he has spent his life empowering average Americans against the super-powerful and super-rich; what was this?

In plot, “Super-Rich” is a G-rated political thriller: a group of aging, real-world billionaires join forces to save America from rampant privatization, irresponsible business, hijacked politicians and stagnant democracy. In substance, it is a mix of polemic and fantasy. The protagonists not only share an impressive understanding of the details of airwave regulations, automotive safety requirements and most of Nader's other pet causes, but also agree—heroes and villains alike—on exactly where America went wrong. And for once, everything goes right. Seventeen high-minded, remarkably cooperative "Meliorists" buy up the media, finance lobbyists, launch a new party and seed a green economy. Then they deliver it all to The People, whom they have strategically prepared for self-government by involving them along the way.

Is this antidemocratic? About three chapters in, it stops feeling that way: the book is intently, obsessively focused on the problem of transforming America into a functional democracy, and that honourable intent can be felt at every turn. But that doesn't solve the problem of how Nader does it. Isn't democracy handed down from on high a sort of enlightened dictatorship? The book has been blurbed as a "practical utopia," but there is something strikingly impractical and dystopian about billionaires granting freedom to the rabble.

The man I sat next to that afternoon certainly found Nader’s case hard to stomach, but he also thought that representative democracy worked pretty well, at least in Canada. If he had felt that he already lived in a modified dictatorship, a better autocrat might have seemed an attractive alternative—and it may be that Nader has himself reached that point. He is in his autumn years, and though he has been named one of the century's most influential Americans for his record of pushing through legislation and sparking civic engagement, he has faced more failure than success. The book was born of decades of frustration: "I have often wondered, What if we had the media this time?” Nader said at his Toronto address. “What if we had money to train people?”

If that money and media coverage came from an organized group of unusually elite people, citizen empowerment and crowd control might start to look a lot alike. But if the gears of democracy have in fact ground to a halt, maybe good government needs all the help it can get. In that case, the Meliorists would be stopping the political machine and setting up another one in its place; they would be waging not democracy but revolution, and schemers and slogans would be par for the course.

Though the book is careful to distance itself from Marxism and frequently refers to the Meliorists as capitalists and old-school conservatives, it does not shrink from revolutionary terminology. At a conference of the villains in the final chapters, a demoralized CEO questions why they bother to fight back: "The Meliorists represent the mildest rebellion we're ever going to see. What do you think is likely to come later?" he asks. "Workers, after decades of loyal labour, are losing their jobs to China as corporations blend criminal communism with criminal capitalism. Their sons are sent overseas to fight and die for crooked politicians and their corporate paymasters. Pensions are disappearing. Those lucky enough to have jobs watch their benefits and pay shrink. The masses aren't going to stay dumb forever just because they're the masses."

The super-rich are not the only ones who can spark a revolution, but if democracy has sputtered out, they might be in a unique position to organize one as a model of efficiency. Nader’s story is plot- and star-driven, but it frequently descends into agonizing demonstrative detail: how to hold effective meetings and hire good activists; which legislative changes would have the most direct impact on the lives of Americans; how to pressure Congress, face down a character assassination, and capture the public's heart. At times it seems less a novel than a manual for saving America with only eight billion dollars and seventeen celebrities—but whether from further degeneration or inevitable revolt, the book doesn’t say.

I worked for Nader briefly, and he spends an awful lot of time digging up reports on the worsening material and political conditions of majority America. It's not unlikely that, from where he stands, American democracy looks just about dead and rebellion lurks on the horizon. Perhaps he’s literally on board with the title of his novel. That would make it not anti-democratic but post-democratic, a book—strangely enough—on how to manage revolution.

But there’s at least some evidence to the contrary. Nader hasn’t given up on old-fashioned democratic involvement quite yet. His Economic Club speech was a small, private event not because he no longer cared to whip up democratic fervour among the masses, but because he used a another event in Toronto to do exactly that: what was supposed to be a larger, public book stop became a rally for protecting Canadian public health care. Still, why should he bother with such well-worn activist tactics if they have not halted the march of privatization, and if—as the book suggests—we need money to fight money, super-persons to take on corporate personhood? At this point, is activism just habit?

Nader ended his presentation at the Economic Club by calling the novel his “answer to Ayn Rand.” There are certain superficial resemblances—length is an obvious one, as is the subordinance of literary merit to the author's ideas. Perhaps the similarities will turn out to run deep. Like Rand, he presents esoteric goals in a widely published fictional work—unusually accessible packaging for a political tract. And if the ultra-powerful, inhumanly talented characters spouting Rand's counterintuitive views can change the lives of freshmen college students year after year, why not Nader's facts and analyses from the mouths of the plain old wealthy? It may prove not to be such an antidemocratic book, yet.