On Starnino’s Nichol

Two poets discuss Carmine Starnino’s controversial essay on Canadian avant-garde legend bpNichol.

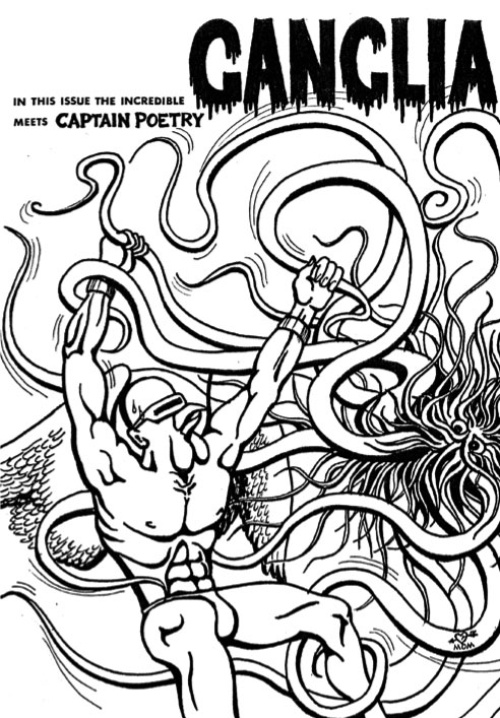

An image from bpNichol's The Captain Poetry Poems.

Jonathan Ball is the author of Ex Machina (BookThug) and Clockfire (Coach House Books).

Maurice Mierau's last book, Fear Not (Turnstone), won the ReLit award for poetry in 2009. He edits the Winnipeg Review.

Carmine Starnino has published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is This Way Out (Gasperau), and the essay collection A Lover's Quarrel (Porcupine's Quill). To read "Captain Poetry," Starnino's essay on bpNichol, pick up a copy of Maisonneuve Issue 39 (Spring 2011) or contact us to order it.

Jonathan Ball: Starnino has long struck me as an excellent poet, a strong critic of lazy lyricism and a terrible reader of the avant-garde. His writings on supposed experimentalists display no affinity, and thus no foundation for a studied response. But with this Nichol piece, he finally appears to be apprehending and appreciating core values of the Canadian avant-garde. As an example, his observation that Nichol saw "Language [as] basically sonic Lego" is spot-on—and even sounds like something Christian Bök might say!

Nearer the end, though, he falls back into his old patterns—arguing that "convention-flouting" is less impressive to readers these days. I agree, but this is another example of Starnino being up to rhetorical tricks rather than saying anything of substance. For the fact is that modern avant-gardists display little real interest in convention-flouting. On the contrary, much recent avant-garde practice involves reviving discarded conventions or transporting conventions from other arts into poetry.

I have long wondered why Starnino insists on writing at length about things he appears to hate, but although he is critical here toward the end, a real fondness for Nichol and an appreciation for aspects of his oeuvre shine through. Finally, some willingness to engage, which I find lacking in his other writings on the so-called avant-garde, which often, as they do here, descend into straw-man bullying.

Maurice Mierau: I agree that Starnino is a strong poet, but he earned my complete attention ever since 2004, when he published this sentence in A Lover's Quarrel: "...we've frittered away the last thirty years valorizing negligible poets who possess feeble imaginations, meagre technical skills, and scant knowledge of the tradition in which they work—and even the briefest mention of it is considered very poor form." This is brilliant hyperbole in the tradition of the quasi-Canadian Wyndham Lewis.

Starnino's new essay here drew me in because it plays against the stereotype readers have already built about him: assuming that he won't be sympathetic to an experimental writer like bpNichol. Perhaps he was surprised at Nichol's satire of the macho posturing of seventies MaleCanPoets, a group that deserved (derisive) laughter as much as sustained criticism. The idea of an experimental writer with a sense of fun and intellectual independence is certainly novel in today's CanLit context, and that aspect of Nichol is nicely brought out here.

Near the end of his essay Starnino notes that the Canadian avant-garde is now more professionalized, more "academically located." This is true at a journalistic level, but I'm doubtful whether an avant-garde still exists for a critic to read either well or badly. Or, to be less perverse, I agree with you that the most interesting poets these days, in CanLit and elsewhere, are busy recycling conventions from all over the place: i.e., they're formalists. It's worth remembering that Ezra Pound, so busy making it new, was obsessed with the Troubadour poets of seven hundred years earlier—that's why Ezra the avant gardener dug sestinas.

I'm curious why you think Starnino is "straw-man bullying." In my view he's made some historically astute observations about Nichol and his work, the sixties, and the book that provides his occasion.

JB: I mean not that he's flourishing a fallacy, but that the avant-garde Starnino seems to believe exists is itself a straw man, one he bullies in a pointless struggle. This essay is a real step forward for Starnino, but he's tagged a solid and insightful meditation on Nichol with a pointless criticism of nobody in particular. I suppose there is a rhetorical strategy here, to buoy Nichol further by noting the lack of a modern-day Nichol, but I could suggest (and have suggested, in Open Letter) that derek beaulieu marries Nichol's energy and concrete interests with occasional bursts of exuberant humour (i.e., in the book he co-wrote with Gary Barwin, frogments from the frag pool). And kevin mcpherson eckhoff, with Rhapsodomancy, has established himself as a possible Nichol-in-embryo, one to watch.

But when Starnino writes that "the most galling failure of our current crop of experimental phenoms [is] humourlessness," I shout "huzzah!" This is a serious charge and, I think, a valid charge. But the fact is that galling humourlessness is not confined to the experimentalists among us. On the contrary, my sense is that this is a greater problem outside of the avant-garde—indeed, parody and absurdity are hallmarks of avant-garde practice. Can we point to a so-called traditionalist who can craft lines as biting as Ryan Fitzpatrick, in Fake Math, when he writes, "My assassin brings me products I love" and makes it fit into the same poem as the silly "I wasn't elected smart guy"? In a book with the line, "A new weapon in the war against explosions: / EXPLOSIONS!"?

Let's even accept Starnino's premise that the Canadian avant-garde is interested in flouting conventions. Flouting conventions is a hallmark of humour! My point is that if one actually looks at the loose group often identified (and even self-identified) with the misnomer "avant-garde," one sees just as much humour as elsewhere, if not more. Of course, the opposite goes—there's a lot of arch, over-serious experimental work, far too much. Should we not conclude, then, that most poetry sucks, that this is Canada's or modern poetry's failure, rather than the avant-garde's? Regardless, all praise to Starnino for pointing out this nation's greatest literary flaw.

MM: The word experimental is a loaded one in Starnino's piece, and it isn't just him. Many of us (poets) assume, for example, that writers who come out of the creative writing program in Calgary, like you did, must be experimental. And that writers who appeared in Starnino's anthology The New Canon must be traditionalists of some sort, thus making them members of a hypothetical mainstream. The problem is we have no mainstream in Canadian poetry. They do in the UK, and to some extent in the US, but not here. Here we've become Gillerized, and poets divide in factions depending what part of the country we're from or what graduate school we went to.

For me the writers who are experimental are the ones playing with convention, and they also are the ones whose work is humorous. I'm thinking of Alessandro Porco's (brief) revival of the limerick, Jason Camlot, David McGimpsey and the extremely funny Suzanne Buffam (especially The Irrationalist). The only Winnipeg writer who's made me laugh out loud while reading in a library is Robert Kroetsch, again because of his willful and knowing play with conventions.

But getting back to Nichol. He was an experimental writer, as eckhoff is today in Rhapsodomancy. Starnino really does a marvelous job of describing Nichol's oeuvre, his working methods with mimeos and throwaway media, his incredible energy and ability to work in multiple genres, his wit, and the publishing micro-industry that's followed in his own micro-industrial wake. Starnino's a fabulous cultural journalist, which leads him to observe the internationalism of Nichol's practice (in the discussion of the concrete poems). Internationalism is something Starnino has advocated in other essays, in the sense that Canadian poets ought to pay attention to the bigger world of poetry.

What's interesting is that most experimental writers are and have always been intensely aware of the international scene (think of Anne Carson and Lisa Robertson as contemporary examples). The provincial poets are the ones reading only the work of the people on their tenure committee or local arts council jury. The real experimental writers are pushing boundaries not by ignoring the past or the world beyond their civic boundary, but by doing a re-mix of the traditional and the new, the pop cultural and the staples of western civ.

Where I part company with Starnino is in his concluding paragraph, where I get the uneasy sense that, even in a sympathetic piece, he might be using experimental in two different ways: one to describe a historical phenomenon now safely dead (1960s experimentalism), and the other as a pejorative label. The problem is he doesn't actually name anyone in the conclusion, and that's why it comes off as a rhetorical flourish—or you could call it "straw-man bullying," which I initially resisted.

JB: I agree with everything you're saying here, and most of what Starnino says about Nichol. And I'm sympathetic to Starnino's overall aim to deliver polemic and passion back into Canadian criticism. But note when Starnino criticizes the Escher-like As in Nichol's The Captain Poetry Poems. After analyzing the poem, Starnino asks, "How can you possibly respond?" But he's just given a response! As elsewhere in Starnino's criticism of the avant-garde, his rhetoric is misleading and his interpretations do not go far enough.

Yes, "The message is obvious: each letter is a rabbit hole onto its own world." Aside from typifying this as a mundane insight, rather than one premised upon and engaged with philosophical thought on the role of language in the production of human reality, Starnino fails to criticize the serious and obvious flaw in Nichol's poem, a flaw in line with the criticism Starnino intends: that the poem is simplistic, its engagement facile.

"Embedded inside—as if readers were stealing a rare look into the soul of the letter itself—is a rolling landscape with a cloud-filled sky." Is that the best glimpse into the soul of a letter than Nichol can provide to us? A visual cliché? Down the rabbit hole is a boring landscape with clouds, rather than the alien world envisioned by the Codex Seraphinianus, where writing occurs when letters are floated down to a page by balloons, and must be tied down to prevent their escape, or some other imaginative rendering of the letter's soul. The world of Milt the Morph that we glimpse in this way is a bland world—just like ours, but poorly drawn.

I don't mean to belittle Nichol, whom I admire, but to point out the ironic flaw in Starnino's criticisms of the avant-garde: that they are neither charitable enough nor even critical enough. They aren't adept enough, though this essay moves him some way toward where he wants to be, in its strong assessment of Nichol's overall practice.

Maisonneuve claims to have tapped me to respond here at Starnino's own suggestion, so I've felt obliged to adopt his forcefulness in an effort not to disappoint him, rather than in parody or distaste. Let me shift from flirting with his style to inhabiting his prose, quoting from the introduction to A Lover's Quarrel and rewriting as I go: "A poem by Bök does not sound like a poem by beaulieu does not sound like a poem by Christakos does not sound like a poem by Moure. Yet to a vision where every avant-gardist is just as bad as every other, the singularity of these poets slips away."

MM: The passage you're revisiting in A Lover's Quarrel suffers from the influence of John Metcalf's worst tendency as a critic: making unsupported generalizations. While I greatly admire Metcalf's work as an editor and a controversialist, it seems to me now that Starnino is moving beyond the blanket statement, while Metcalf hasn't and won't.

As for the Nichol revival, it's probably no coincidence that the new edition of The Captain Poetry Poems was published by BookThug, the same people who published Elizabeth Bachinsky's first outing (and some guy named Ball). Now, is Bachinsky an experimental writer or an unusually cool traditionalist? "Heuristics rhymes with fish sticks," writes George Murray in last year's Glimpse, a book of aphorisms—wild new experiment and also part of the ancient western canon.

To read "Captain Poetry," Starnino's essay on bpNichol, pick up a copy of Maisonneuve Issue 39 (Spring 2011) or contact us to order it.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—High Wire Melodies

—Interview With David McGimpsey

—Interview With Suzanne Buffman

Subscribe — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook