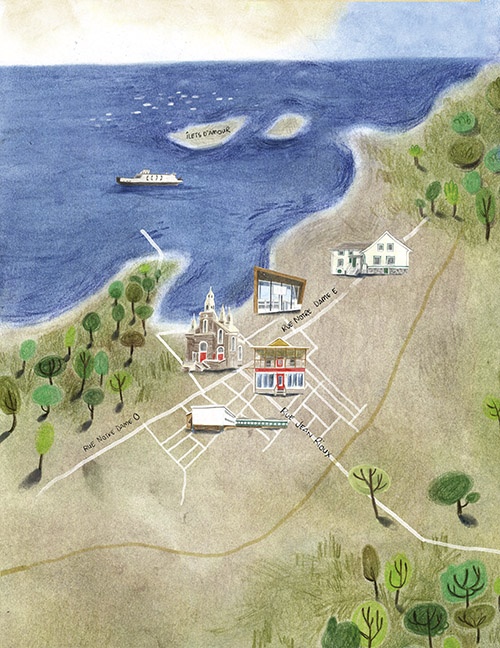

Illustration by Amelie Dubois.

Illustration by Amelie Dubois.

Tout le Monde en Parle

Jasmine Irwin went to rural Quebec for adult summer camp and learned that French immersion is not for the weak.

It was bizarre that the cloud was raining only on me. It was an unseasonably warm, clear day for Trois-Pistoles, a town in northeastern Quebec whose spring is typified by a damp, misty cold that rolls in off the banks of the St. Lawrence river. I was cycling back to town, having decided to take advantage of the sunny weather after class and before I was expected for dinner.

At eighteen years old, my participation in this five-week-long French immersion program represented the longest time I had ever lived outside of my hometown, my first foray into adult independence. Something as simple as going for a bike ride on a whim, without telling anyone where I was, felt illicit and almost Kerouac-ian: like, hey man, sometimes a girl’s gots to ramble.

Yet even as the sunlight still glinted off the river beside me, there it formed: a small, dark cloud, a menacing clump of grey in an otherwise azure sky, pelting down on me like a personal terrarium. I rode most of the way back to town as a cartoon depiction of depression, the cloud following my bike as I moved through the tall grass, then pedalled down near-empty roads.

I got to my “host house” in time for dinner but was soaked through, much to the confusion of my fellow students who had gathered there to eat. Yet again, I found myself in possession of a serviceable dinner story (“A personal cloud? Who am I, Charlie Brown?”) with no viable method of delivery, a plane without landing gear. Every thought or question that crystallized in my head crawled out of my mouth one mangled shard at a time: each pithy anecdote became a rambling, shaggy-dog story with a Mad Libs helping of seemingly random nouns.

Merde.

Like all English visiting students in Trois-Pistoles, I had made a pledge to speak French and only French only during my five-week course. Not just in the classroom, not just during our mandated Québécois cultural activities, but everywhere: at dinner, gossiping between classes, huffing up hills on our school-led weekend nature excursions. Not only were the locals in Trois-Pistoles supposed to help by speaking with us, they were deputized by the language school to monitor our use of English and to report us if we strayed.

The pledge also applied to conversations in our billet houses (where students slept in the homes of local Québécois residents) and our “meal houses” (where we would gather to eat dinner and lunch together in a large group assigned to another local, seemingly always a woman). Our personal cook was a woman who, to preserve a tidbit of her privacy, I’ll call Renée. Her children had moved out long ago, but she treated her anglophone wards with a motherly combination of exasperation and indulgence: quick with both a sharp remark and a second piece of dessert.

Now, standing in Renée’s kitchen, I tried to explain my sodden state, courtesy of an individually packaged serving of inclement weather. “The whole mini rainstorm thing felt a little personal…” I blurted in English, in an attempt to salvage a punchline. Feeling the eyes of Renée on me, I switched back to French. “Like maybe because I am...bad.”

“You are bad,” Renée said, shaking a spatula at me. “It was a punishment.”

“What? For what?!” I asked, laughing.

“For always speaking English,” she said, carrying a tray past the counter to the crowded table. “When you should be speaking French.”

Asked if I speak French today, I do the dance we negligent anglophone Canadians have perfected: the apologetic wince, the hand gesture, un petit peu. This is not an especially helpful categorization; in my experience, people use it to describe a proficiency level that runs the gamut from “I remember a song about farm animals from the fourth grade” to “I could help you draft this affidavit, but it might need a proofread.”

Before I did the Trois-Pistoles program in the spring of 2010, I had done a single year of “extended immersion” in the seventh grade (my parents, a bit too late, doing a “rush for the doors” on my prepubescent brain plasticity) and had spent the summer I was sixteen working at a daycare in Sherbrooke, Quebec, where I learned such important French phrases as, “Take that out of your mouth” and “You can wipe yourself, Antoine.”

Last year marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Official Languages Act in Canada, in 1969. The bill was designed to increase language aptitude in the public service, a relatively small swathe of the population. But even if it had limited impact on changing the rate of overall bilingualism, the Act carried symbolic weight, enshrining Canada as a single nation of two languages. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, in introducing the legislation, extolled it as a step towards a bright and prosperous future: “such a country will be more interesting, more stimulating and, in many ways, richer than it has ever been.”

The “richer” part may be true, at least for those who have knuckled down with a Bescherelle. Seventy percent of Canadians believe that bilingualism can lead to better job opportunities, and research shows that bilingual Canadians do earn more; in Quebec, you’ll earn about 8 percent extra if you speak English as well as French, while in the rest of Canada, anglophones earn about 5 percent more for having French skills.

By all indications, French language education and immersion has exploded in Canada: enrollment in French immersion schools around the country increased by more than 20 percent from 2011 to 2016. However, many feel they’ve missed out, either by their parents’ choice or by their own. Language acquisition is a lot like piano lessons or hearing long stories from grandparents: children are the most likely candidates, and also the most grudging participants.

According to the CBC, French as a Second Language classes for adults have ballooned in popularity: seven school boards across Ontario offer programs, some with a “huge wait list.”

The federal government anticipated this aspiration. It didn’t completely ignore everyone except bureaucrats; after the act’s passage, Ottawa created a public bursary to increase both bilingualism and Canadian unity. “Explore” (formerly the “Summer Language Bursary Program”) is primarily aimed at students in college or university. The Explore program sends students to different locations around the country for weeks at a time to learn their second national language. Through Explore, students receive a stipend to cover the costs of tuition and accommodation during the course. The “École d’Immersion Française de Trois-Pistoles” has been incorporated into Explore, even though it predates the federal program by nearly forty years.

I applied to Trois-Pistoles during my first year of university, received a bursary, and proceeded to spend the intervening months agonizing. I wanted to improve my language skills, but I was very nervous about what the five-week course would entail: I didn’t know anyone else going. “I’m on the train right now for hour six of sixteen…” I wrote in a Facebook message to a friend. “But I am terrified right now... I feel like the people of Troispistoles (sp) are likely to a) laugh in my face in a derisive yet classy french-ish way b) fail me on my french courses c) make me live with the seals by the river.”

In particular, I was worried about the “No English” pledge. The program enforced a three-strikes policy: you received three warnings, and then you could be sent home early on the shame train courtesy of VIA Rail. I worried both that I would be able to follow through on the pledge (resulting in no friends, monkish isolation) and that I wouldn’t be able to follow through (resulting in early departure, ignominy to me and my family, and having to reimburse my bursary to the government).

The rigor imposed by the rules I had read in the handbook seemed near-Orwellian: “The [French only] rule applies not only to the classrooms and other areas of the School, but also to the homes of the families where you live, the town itself and the places outside of Trois-Pistoles visited on excursions... Students who persistently contravene the rule will be given three warnings (avertissements) that they must improve their behaviour.” The school guidelines encourage that students even watch movies and listen to music in French at their homestay. It was hard to picture myself doing this using the French songs I knew: wouldn’t others object to a playlist of “Alouette” and only the bridge from “Lady Marmalade”?

Inevitably, it seemed, I would have to choose between my two great fears: awkward silences and breaking the rules. It was going to be a rough five weeks.

Trois-Pistoles is a town of about three thousand people in the Basque region of Quebec. According to legend, the town is named for a lost goblet a clumsy seventeenth-century sailor dropped off a ship while it was moored near where the town is now. He exclaimed, “Three pistoles lost!” (pistoles being gold coins). As butterfingers incidents go, it seems like a decent outcome: the designation of a town that endures three hundred years later seems vastly better than say, a smashed phone screen.

Catholicism may have fallen out of favour with many Quebecers, but it has left the province with architecture that punches above its weight. The nineteenth-century cathedral of Notre-Dame-des-Neiges is an ornate, five-spired edifice that still dominates Trois-Pistoles’ landscape. The inside is similarly grandiose, with marble and gold molding that would put a Vegas casino to shame. The town has notoriety that exceeds what one might expect from its small population, lending its name to a Tragically Hip song, “Three Pistols,” and a popular UniBroue strong beer.

However, there have also been many short-term residents that have “spread the word” about Trois-Pistoles: the town is home to the oldest continuously operating immersion school in Canada. In 1932, then-president of the University of Western Ontario (usually just called “Western”), W. Sherwood Fox, wanted to open a school where students would be immersed in a francophone community during their summer break, replicating a formative experience he had as a young man. In his autobiography, Fox wrote that “establish[ing] a summer school in Quebec where English speaking students could readily acquire at least a limited spoken French had been a germ kept alive in my memory for many years.” For Fox, the school was to be an endeavour not just of language acquisition but of national understanding and harmony. He was clearly chuffed that the program had been acclaimed by academic peers for its potential to strengthen Canadian cooperation. He wrote in his memoir: “Let the bonne entente continue!”

Since then, thousands of visiting students from all over Canada—and even from around the world—have disembarked from the small train station and been corralled into the school auditorium awaiting pickup by their new “family.” From its inception, the program has been wholly dependent on the cooperation and hospitality of the residents of Trois-Pistoles to welcome students into their home. They also receive a per-student remuneration for their efforts. Each year brings two separate cohorts of about 250 students each, divided between spring and summer sessions, who bunk in with around ninety participating host families.

For those earliest visiting students, and certainly even now, Trois-Pistoles feels a world away. It’s over a thousand kilometres away from Toronto, a stretch roughly equivalent to Paris to Prague. More than simply the geographical distance—we Canadians are accustomed to a certain homogeneity across staggeringly large expanses—it is the distinctive and unapologetically Québécois culture of Trois-Pistoles that feels, well, foreign. For the rest of Canada, tastes of Québécois culture are often delivered in sanitized, anglo-friendly packaging. Trois-Pistoles is less “Celine Dion and smoked meat sandwiches” and more “Gilles Vigneault and fèves au lard.”

The cultural differences are more than just English/French. Many visiting students aren’t used to living in an actual small town, the kind of community where the nearest McDonald’s is forty minutes away and shopkeepers and customers greet each other by nickname. Age matters, too: some visiting students are “mature learners” or families, often paying their own way or funded by their employers, but the vast majority are between eighteen and twenty-five and funded by student bursaries. In Trois-Pistoles, the median age of residents is fifty-seven (the town is classified as being in “demographic decline”) and many host families are empty-nesters looking to use their spare bedrooms for some extra retirement income. Canada’s recent federal election provided a stark reminder that generational gaps are their own distinct form of national discord: Ipsos polling indicated age was a core determinant of what issues voters cared about and who they were prepared to vote for. While not the intent of the program, the hosting arrangement also brings the young and the old together. D’Accord, boomer!

I shouldn’t have worried so much on the train ride: while my French was by no means excellent, I could at least hold a (boring, erratic) conversation. Much to my surprise, there were attendees who spoke almost no French, whose faces fell apologetically after a cursory “Ça va?” One young married couple at Renée’s dinner table was from Alberta: Ryan wanted to be a politician, he told us, and thought he should be improving his French. His wife Kelly was there to accompany him, an act that quickly became apparent as a kind of spousal martyrdom. Kelly’s French was only a touch better than the average Canadian’s Swahili.

The school in Trois-Pistoles is prepared for these kinds of students, and believes that immersion can be just as effective for total beginners. According to research, the benefits of language immersion for adults have less to do with the speed of learning and more to do with the type of learning. While classroom teaching can be just as effective as immersion in promoting language proficiency, a study by researchers at Georgetown and Illinois University showed that adults who learn in an immersive environment demonstrate more “native-like” language development in brain scans. Immersion can trick your brain into learning like you’re a Montessori toddler.

What makes the immersion program at Trois-Pistoles so unusual is that students are responsible for “immersing” each other: most of your time is spent with fellow students. In most immersion experiences, you are alone in your linguistic pursuit, whether by design (on an exchange), or by necessity (arriving as a newcomer in a different country). The frustration or embarrassment of the whole awkward endeavour is ultimately eclipsed by the pressing need to communicate: to know where the bathroom is, to indicate your deadly shellfish allergy, to interject that you, too, love Die Hard.

By contrast, there is a kind of ridiculousness in the arbitrary, self-imposed hardship of adults choosing to communicate, poorly, in a second language when all parties involved could easily switch to their native tongue. It’s kind of like eating a meal, but instead of doing it normally, everyone agrees to do the party game where the eater is blindfolded and someone else has to go behind them and act as their arms in order to feed them. The meal gets eaten, but it takes a long time and it makes a mess.

In writing this, I spoke with other friends and acquaintances who stayed in Trois-Pistoles as students. My friend Alexis, who went in 2017, told me that she thought that the vulnerability necessitated by the French-only pledge was part of the reason why people who had done the program felt such a fierce sentimentality about each other and the town itself.

“It was a really...adorable time,” Alexis said, laughing. “There’s a childlike experience of learning a new language. It kind of rockets you back to this mentality of, nothing is meaningless. It slows you down, forces you into the present—it’s not weird to comment on the colour of a table, or on how something tastes. Every sentence you get out of your mouth is like, good job you!”

For beginner or intermediate students, to speak is to fail. There is a camaraderie that forms among students as they throw themselves out of the trenches of their dignity and into the breach of Sounding Like a Real Dumbass.

If students are language-babies, the people of Trois-Pistoles are in loco parentis: waiting tolerantly as a student holds up the line at a till with makeshift charades, or nodding encouragingly through awkwardly proffered non-sequiturs: “The river...it is very nice. I am...looking the seals.” Host families, in particular, take on the responsibility of part-time teachers. “You’re not aroused to go kayaking,” Renée would interject into our dinner conversation, when one of us used the French adjective for “excited” wrong. Or, “You’re not going to eat a prostitute later,” when we garbled the word for poutine.

According to current Program Director Kathy Asari, the integration into the homes and lives of local residents is what makes the program at Trois-Pistoles special. She’s biased, she told me with a laugh, but she thought that long before she became its director. As a student years ago, Asari did Explore in two locations, and said that her time in Trois-Pistoles was markedly different. Unlike other language schools where students bunk together in dorms after classes and activities are done, the partition between “learning” time and “living” time is blurrier for students in Trois-Pistoles.

While she knows that can be tough and tiring, she thinks that most students ultimately understand—and enjoy—the benefit. “Pedagogically speaking, it’s just a different experience,” she told me on the phone. “When you’re in someone’s home, it’s different than a residence room or a classroom. You build relationships. And that’s when the French pledge becomes not just a commitment to the program, but to the community itself. And we trust students to take advantage of that opportunity.”

While the opportunity seemed great in theory, I found it hard to enact in practice. I still spoke English—all the time. Even with the hilariously panoptic setup of the program, the “No English” rule was hard to enforce. Many, many students were self-disciplined even among themselves in downtime, dutifully conjugating and tu-toyering their way through group conversations far out of teachers’ earshots. Out of respect, I always spoke French, or at least “Franglais,” around acquaintances, but with my friends my patience waned: jokes were too confusing, stories too slow, controversial gossip much too vulnerable to misinterpretation.

I was genuinely fearful of avertissements—the official warning system—but other than Renée’s consistent chastisement (C’est assez, Jasmine!) and a few tutting locals, there was not much heavy-handed enforcement outside of class. Others also reported that the rule was not as stringent as they expected.

“There were people who would call us out for speaking English at the bar, but it was always in a joking way,” said Will Pearson, another program alumni. “I think the locals get a kick out of the program. They like to play along—it’s part of the game.”

When talking to former students, it’s remarkable how much Trois-Pistoles can feel like an experience you had “together”, even if you were actually there years or even decades apart. Nostalgia is easily summoned and near-universal for alumni: the sunsets by the river (beautiful, lingering Technicolor feasts), the poutine (best at Cantine D’Amours), the bars (Chez Boogie), that Big Hill (the humiliation of having to get off the bike and walk!). Bikes are central to the student experience in Trois-Pistoles: students can rent a normally janky but serviceable bike for the session, and it gets you everywhere. One girl in our broader friend group didn’t rent a bike, and it became a real social liability.

The actual day-to-day contours of the program itself have stayed consistent over many, many years. French class in the morning, taught at the high school. Lunch, back at host house. Atelier—an activity—in the afternoon. Students choose their ateliers at the beginning, and the choices run the gamut from “Biking” to “Drama” to “Gardening.” I did “Music,” which mostly involved hanging out in an abandoned blacksmith’s forge, boinking around on random instruments while our coureur de bois-looking teacher tried to wrap our molasses mouths around uptempo Québécois folk songs. We even had recitals, including one at the elementary school that resulted in a jarring role reversal of a choir of adults earnestly screeching songs about ducks to an audience of indulgently approving second-graders.

After ateliers, a short break, then dinner at your host house. Each evening had additional activities: a poetry reading, an intramural game, one of many, many themed “soirées.” On the weekends, there are socio-cultural excursions available: visiting a provincial park, a weekend trip into Quebec City. My younger cousin did the program much more recently, and I asked her if the ubiquity of smartphones made adherence to French immersion tough. Not at all, she said. Her friends texted each other in French, curled up and watched French movies on laptops. She did laugh, though, when I told her that we used to keep physical dictionaries around to look up words.

For a kid who had been “bad at summer camp” (diagnostics: unathletic, wore a sun hat, tried to make friends by sharing facts about Medieval heraldry), Trois-Pistoles represented everything I felt like I had fumbled: wholesome outdoor adventure, fast friendships with an intimacy that far outpaced familiarity, campfires and group pictures.

Of course, students still pursued decidedly adult ateliers of their own. The lower legal age in Quebec and the mostly university-aged participants meant that many nights were spent drinking (adherence to the pledge was inversely proportional to beers consumed). For me, Trois-Pistoles was not just an opportunity to try French, it was also an opportunity to try a truncated version of growing up. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I tried to shoehorn a Bildungsroman worth of formative experiences into five weeks. That summer in Quebec was where I first started smoking cigarettes; where I first tried a joint (because I thought it was a cigarette); where I got my first and only tattoo; where I kissed a total stranger for the first time.

Life in Trois-Pistoles felt like it came with metaphorical, if not literal, training wheels: tipsy experiments like “do you think I can bike home with my elbows on my handlebars?” (answer: no) had minimal consequences. I got comfortable making mistakes in Trois-Pistoles.

There is lemonade in my fridge that has been there longer than I ever was in Trois-Pistoles. In this context, the nostalgic and almost proprietary feeling I have in relation to the community there makes no sense.

Normally, you might think that where you slept would be the place for building intimacy with your hosts and fellow students: those moments of padding down the hall, toothbrush in mouth, or returning a wayward sock. But for me, and for many others I spoke with, our “meal families” tethered us to Trois-Pistoles. The couple who owned the house where I slept was nice but seemed mostly bemused by the presence of four university girls in their home. Neither of our hosts were Trois-Pistoles natives, but had recently decided to retire there. They were hosting for the first time, and I got the impression they were gamely trying out a local fad, like lawn bowling, that they weren’t quite sure was the right fit. I spent as much time as I could out of the house, and much of that time sitting around the kitchen table at Renée’s.

After dutifully avoiding the freshman fifteen the year before, the “Trois-Pistoles ten” snuck up on me. No amount of biking or outdoor programming could cancel out the twice-daily desserts, the hearty cream-based soups Renée served us. She would let a small group of us linger for hours after a meal was over, drinking coffee after coffee and filling the house with near-shouting and horrifying conjugations. In hindsight, this strikes me as absurdly generous: she was given a stipend to feed us, not to let us rifle through her living room in search of old board games or use a landfill’s worth of Keurig cups.

On some occasions, Renée would stop puttering and sit down with us to chat, in French, of course. We liked goading her, probing her, trying to elicit one of her throaty laughs. As the daughter of teachers, I am familiar with the misalignment of memory between mentor figures and their wards: the quickly concealed confusion on my father’s face when he runs into an effusive former student at a gas station. To me, Renée was a central figure in a formative experience. I suspect that for her, we were just another cycle of coltish houseguests: near-incomprehensible, then slightly more comprehensible, and then gone.

As Renée became more familiar with us, she loosened up, became more familiar—even let us in on some local lore. Once, she told us about a person who had been killed in Trois-Pistoles many years prior. According to her, the murder was connected to powerful people in the town whose families and associates had reason to keep the real story quiet. She knew the identity of the prime suspect, Renée told us, because she had been sleeping with a police officer at the time.

We were all incredulous, that something so lurid and Agatha Christie-like could have happened in a town also known for cheese curd production. “Do you still see the killer?” I asked her, breathlessly. “Sure,” she replied. “At the grocery store a few days ago.”

Around the same time, I learned that Le Triolet, a boarded-up bar we pedalled by regularly on the main street, had been shut down in a cocaine-trafficking bust just a few months before we arrived. It was one of only three bars in town, so it had been big news. While I found stories of these unexpected scandals thrilling, they also upended my sense of the natural order of things. We, the students, brought the excitement to this town. Didn’t we?

Even for those people of Trois-Pistoles who aren’t acting as hosts, most of them are overwhelmingly pleasant to visiting students: some just benignly accepting, but many more openly welcoming. Even with a CPP-ready population, it’s hard to believe anyone in the town is old enough to remember a time before the language students began their annual pilgrimage. Every year they arrive right on schedule, as reliable and as noisy as migrating birds.

The fact that Trois-Pistoles exists in the way that it does is a testament to the triumph of fierce Québécois language protectionism. Hundreds of years after Montcalm took a musket ball at the Plains of Abraham and France said au revoir to its North American holdings, Trois-Pistoles is still unquestionably French, and distinctly Québécois. It’s easy to ridicule Quebec’s draconian approach to language and cultural preservation (more recent laws governing religious expression, rife with xenophobia and racism, deserve more than ridicule), but the proof is in the pâté chinois, so to speak, when visiting the Basque region.

Results from the 1995 referendum showed the area around Trois-Pistoles voted firmly for Quebec to leave Canada: 63 percent said Oui to becoming a sovereign nation. Seperatist sentiment in Trois-Pistoles isn’t overt or confrontational, but isn’t hard to find, either: Vive le Québec libre graffiti is still scrawled on bathroom stalls, and locals will speak with you about their opinions on separatism. The recent resurgence of the federal Bloc Québécois has been credited in part to the party’s pivot to older, francophone voters, like the main demographic of Trois-Pistoles.

The town’s massive involvement in this federally funded bilingual effort is a bit ironic, then—at least, an Alanis Morissette kind of ironic, where something is just kind of contradictory and/or a bummer. For a region that has struggled with feelings of resentment and dissociation with the rest of Canada, the influx of students who are earnestly committed to the project of bilingualism and “national unity” must provoke some ambivalence. Sure, you could see each stammering, wide-eyed anglophone as one more stitch in the bonds of a bilingual Canada: but could they not also feel like a tiny nail in the coffin of a unilingual Quebec?

Claude Rousseau, the local bar owner, had a pessimistic view of the program’s impact on Canadian esprit de corps. “I don’t think it helps mitigate any of the tensions between francophones and anglophones,” he said. “Those problems will always be around. An immersion program won’t change that.” Students are there to “learn French and party,” he said. Even so, he said the large majority of locals still liked the program—students bring energy and life to the community, and provide good business for local shop owners.

I asked the school’s director, Kathy Asari, about navigating this tension. She said that this is something the program tries to embrace: not endorsing a pro- or anti- separatist position, but rather just owning that students are there in part to learn about the history and culture of the province, of which separatism is a part. Aside from the organic conversations students might have with their host families or locals, the school specifically brings in speakers to talk about Québécois history, answer questions, and foster open discussions among students.

“Anglophones have their own idea of what Québécois would like to have, or what they want from separation, and often these ideas have very little to do with the reality of how Québécois feel,” Asari said. “Having these forums are important: it makes space for conversation in an environment that isn’t politically charged. And we hope they walk away with broader context in the back of their mind, and maybe have a different perspective to bring going forward.”

I’m embarrassed to say that my own perspective on separatism before Trois-Pistoles was simultaneously hazy and condescending: a jumble of grainy photos of the FLQ crisis and a sense of Quebec as a sort of petulant teenager unable to leave home, resentful and brooding. I feel like that summer armed me less with a specific opinion than an elevated sense of empathy and nuance. In the intervening years, I’ve been impatient and outspoken with people who make the same flippant comments I myself would have made before 2010.

Asari says that’s all they hope for: that students become more open minded. “I always tell people: you come here to Trois-Pistoles to learn French,” she says, “but I hope what you actually learn is to communicate.”

The strangest thing about Trois-Pistoles, looking back, was that almost everyone I know who has done the program—or strangers, when it comes up—seemed to have a good time. This is the kind of universal agreement normally reserved for experiences like watching The Office or wearing reading socks.

I remembered some of my fellow students receiving the dreaded avertissements, as did former students I spoke to. One recalled a special all-student assembly where a more general dressing-down was delivered. Asari, for her part, alluded to collective reminders being administered to students about their commitment to the community. But none of us former students remembered even hearing about a participant actually being sent home—was the process so shameful that it couldn’t even be spoken about?

When I asked for numbers from Western, I was genuinely surprised by the answer. A representative of the program wrote: “In recent history, there have been no students sent home for breaking the French-only rule. The pledge is in place to remind students of the commitment they’ve made to themselves and to the country (especially those who have received government funding through the Explore bursary) to learn their second official language.”

We were subject to a kind of linguistic Elf on a Shelf, I realized. Those of us who had been “getting away” with speaking English hadn’t really been getting away with anything at all. Trois-Pistoles held another lesson of growing up: normally, you only get out of experiences what you put into them, and you can’t rely on others to hold you accountable. The punishment cloud was right: I was speaking English—furtively, after checking my surroundings—when I should have been speaking French. The only one who missed out was me. Several friends who have completed the program have gone on to become French teachers, and another was a French-language tour guide at the Juno Beach Centre in Normandy. Meanwhile, I remain a card-carrying member of the petit peu brigade.

This spring, the town will be gearing up to welcome its eighty-eighth cohort of students in 2020. I hope the pledge scares them a little too—at least enough to believe the people of Trois-Pistoles are listening in.