Revolution of the Two Ahmads

Few events have affected the geopolitics of the Middle East more than the Iranian Revolution. Abou Farman gives a firsthand account of young idealists caught between religion and politics.

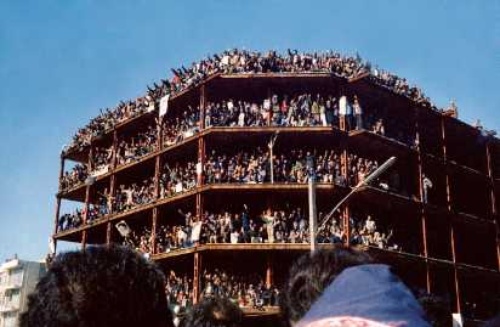

Photograph by Akbar Nazemi.

Ahmad, the son of our family’s gardener, wanted to be a getaway-car driver. Not just any old getaway driver. He wanted to be like those guys we’d seen together one night on the small black and white TV in the pantry, the Baader-Meinhof Gang, West German urban guerrillas with a penchant for BMWs and Mercedes.

Images of the Baader-Meinhof Gang were probably among the first accompanied by the caption “terrorism”on television news in Iran. Whatever the word’s intended meaning, it has only ever referred to “the bad guys,” but in the Iran of the 1970s many had developed a deep sympathy for political outlaws. After all, they were struggling (like so many Iranians) for a world arranged somehow differently, with more justice and more freedom. Ahmad harboured similar dreams, but at age sixteen, he hoped to get in a few joyrides on the way to that better world.

When he was a toddler, Ahmad had stuck his fist inside a wood-burning oven, scorching his left hand down to a charred stub. All he had left were finger stumps, ugly as cigar butts. The grafted, discoloured skin was taut like plastic in some places, wrinkled like an old man’s elbow in others. Nothing he could imagine now or in the future could help him fix that—not God, not modern medicine, and certainly not the wealth and influence of his dad’s employers. Ahmad didn’t like school or work, but most of all he hated being powerless. The only influence he felt came from waving his frightening fist in our faces.

His father, Mr. Nabi, often found himself frantically searching for his son. Ahmad, it would turn out, had taken off on his dad’s moped again, and was zipping around Tehran, a feverish city of four million. The moped was not the ideal getaway vehicle: you had to pedal hard to start it up and it could only do about 20 kilometers per hour. The double-sided khorjeen draped across its back—a colourful, woven sack traditionally slung over donkeys — smelled of wet lambswool, petrol and cilantro. But it had a motor and wheels, and in Ahmad’s imagination, it could take corners like a black Mercedes.

Whenever Ahmad came around to our house, I’d run out to see him. He was four years older than me, and more rebellious. He smelled of danger. He never said anything concrete about where he’d been and what he’d seen but I always got the sense that he’d been somewhere, seen something, or was involved in some big plan. He’d shake his head impatiently, knowingly, and say, “Things are happening.”

And they were.

One Friday in September 1978, Ahmad took off again on his dad’s moped. The heat of the summer was subsiding, the promise of a long freshness lay ahead and suddenly a million people were marching on downtown Tehran to protest against the Shah, his regime and society as it had been arranged for them. The revolution was blooming unexpectedly in early fall.

The signs were unmistakable, though no one knew quite how to read them. The religious city of Qom had experienced demonstrations. A few people had been shot. The Shah had declared and lifted and redeclared martial law. Liquor stores, movie theatres, and other “dens of corruption” had been arsoned around the country. The universities were boiling over with leftist ideological passion, and through the year a series of workers’ strikes (especially those in the petroleum industry) had frightened the silk pants off the royal state. Strikes by oil workers!? The organization, the unity and the power they implied struck right at the heart of the state. Then, in the oil-producing southern port of Abadan, Cinema Rex was doused with cheap Iranian petrol and set on fire, killing 400 moviegoers.

Whispers around the schoolyard said the Shah’s secret police had set the fire, or maybe the CIA; other rumours fingered the communists, the left or union organizers. That summed up the two main forces in the world at the time: right against left, West versus East, each projecting images of its own rightful victory in the march of Modern History. It was only years later that everyone began to blame the cinema fire on the mullahs, the ultimate victors of the revolution, who came out of nowhere to blindside History itself.

That September, when the radio announced that martial law had been re-declared, Mr. Nabi changed his boots and rushed to get home before curfew, but his moped was nowhere to be found. Ahmad had got wind of a huge protest in Jaleh Square and driven down there on his getaway moped. That was the place to be on September 8 if you wanted to raise a charred fist against the feudal skies.

The revolution had many peaceful days, days when soldiers refused to open fire and dismounted their tanks to embrace their brethren and have red roses pinned onto their fatigues. But this was not one of those days. The details were never clarified. Troops fired on the protestors and the army’s US-made helicopters swooped down, chasing crowds out of the square and into surrounding alleys. Later that night, trucks arrived and carted the corpses away to dumps outside the city. No one is certain whether a couple of hundred died or a few thousand, but during a stand-off in an alley somewhere, a gardener’s son got caught in the crossfire and his dreams of freedom, of getting away in a black Mercedes, lay lifeless next to an upended moped with its wheels spinning in the air.

REVOLUTION. On the one hand, it means a dramatic break, a new start; on the other it describes a completed path around a circle, ending up in the same old place, over and over, like a wheel spinning. So in one word we see two opposing senses of time, one open and linear, the other closed and cyclical. History is change; history is repetition.

Unlike uprisings, rebellions insurrections or conquests, revolutions are built on grand visions of history and progress, legacy of the Enlightenment’s quest to create a rational world of equality, safety and opportunity for all by breaking the hold of the aristocracy’s inherited power and privilege. From each according to his ability and no need for getaway car drivers. Let us march, then, you and I, with a million others down this path toward a better life, sharing our potential and purpose as one. History moves towards fellowship. Washington, Robespierre, Lenin, Mao and yes,Khomeini may be considered equal heirs to this modern vision of society.

By the ’70s, though, the promises of previous revolutions seemed bankrupt. Capitalism thrust people into the world as solitary, unequal individuals ready to put a real or metaphorical gun to each other’s heads for a dime of profit. Communism turned people into instruments of the state. Nationalism was an emotional Pavlov’s bell ringing people to their feet in large stadiums to hail megalomaniacs. Instead of a humanistic dawn, the global landscape was silhouetted with inglorious pumpkins.

Down into modernity’s midnight floated the darkly-robed and white-bearded Ayatollah Khomeini. The Ayatollah—literally meaning “Shadow of God”—first came to us as a blazing image on television. Exiled to Iraq, then to a Parisian suburb with the noble name of Neauphle-le-Chateau, he kept repeating his most important mantra, “Neither East nor West.” He spoke of a world beyond money, state and nation. When he declared, “All as one” or “All together,” he reached out to large, forgotten swathes of the world, renewing their sense of communion and significance. And who could ask for anything more than a sense of significance in the world? Islamic activists and ideologues had been around since the nineteenth century, cobbling together a hodgepodge of ideas about self-determination, imperialism and authenticity. But it was the practical victory of Khomeini’s revolution that made Islam available as a viable modern political identity. Hundreds of millions everywhere took it on and the rest, so to speak, is history. Whatever else one might have to say about Allah or Allah’s bearded shadow on earth, the fact is that the Ayatollah changed the world. In many ways, we’re still living in the world he created.

These days, with religion playing politics everywhere, it is difficult to recall how improbable a religious revolution seemed thirty years ago. An Islamic Republic sounded so retrograde, so outdated that even clerics feared the idea at first; while everyone else, from the democratic centre to the communist Tudeh Party, underestimated the political potential of Islam. What could a soft-spoken, god-fearing 78-year-old anachronism do? With his bushy eyebrows ending in a sharp point and those staunch eyes staring out from under all his facial plumage, Khomeini looked like an extinct species of owl, not a fearsome revolutionary leader. The young engineers and architects—they were the ones to worry about, bursting out of universities with hot ideas in their heads and blueprints for a better future rolled tightly under their arms. The paradigm was still the Cold War and the enemy was communism and Reds like the Baader-Meinhof Gang.

THE IRANIAN REVOLUTION BEGAN, for all intents and purposes, as a secular, leftist uprising. Throughout the 1970s, the unions organized worker strikes, Marxist students distributed leaflets, guerrilla groups camped in the woods, and exiles mobilized anti-Shah sentiment abroad (the Baader-Meinhof Gang itself was formed in the aftermath of a visit to West Berlin by the Shah of Iran, after a protestor was shot by German police). It was the left that “educated the masses”—from soldiers to students to shopkeepers—toward revolution. On weekends, when thousands flocked to the mountains north of Tehran to hike and picnic, leftist organizations would take turns laying down photocopied pages of banned books on the trail. By the time hikers reached the top of the trail, they would have sidestepped their way through a chapter of Das Kapital and gained a different understanding of social class and surplus value.

There were good reasons for revolutionary sentiment. In 1953, the United States engineered a coup to oust the popular, democratic Prime Minister, Mohamad Mossadegh. That ended the country’s slow but sure steps towards political democracy. Backed heavily by the Americans, the Shah took total control of the state and outlawed the Soviet-supported Tudeh Party along with all other dissident voices, including clerical ones. SAVAK, the Shah’s notorious secret service, jailed and tortured as many leftists as it could find.

Then, in January of 1979, the Shah kissed the tarmac of Mehrabad airport and flew into wandering exile. Without the Shah’s regime and his American imperialist puppeteers, the country experienced a few months of turmoil followed by a raucous year of democratic struggle. Leftist groups broke open the prison gates and released thousands of colleagues. They attacked the army barracks, and their ranks and weapons caches swelled. People of all convictions demonstrated regularly, even as the army held out. On February 1, 1979, the Ayatollah returned from exile. Eleven days later, the army collapsed, its arsenal fell into the hands of the people and the radio changed its greeting to This is the voice of the Iranian revolution.

Hundreds of thousands celebrated on the streets. Women with and without veils marched for their rights. Newspapers printed whatever they liked. Other exiled leaders returned as well, including my aunt, Maryam, who was a pioneering feminist. Accompanying Maryam was her husband, Nouredin Kianouri, who was head of the Tudeh Party and whose first name ironically meant “Light of Religion.” I remember Kianouri as having merciless eyes. We visited them once in East Berlin where they were being humbly housed in exile by the East German government. We flew to West Berlin and walked across Check Point Charlie at night, dragging suitcases across the spot-lit sliver of no man’s land between West and East. It felt like we were in a movie. Maryam and Kianouri picked us up on the other side and drove us to their small house outside Berlin. On the highway, the car door swung open by accident and I almost fell out. As my sister grabbed my arm, I saw Kianouri looking back at me in the rear view mirror. He said nothing. His expression did not change. He did not slow down.

My aunt and Kianouri honestly thought the revolution was theirs. The Tudeh Party aligned itself with Khomeini and a hybrid of Islam and Marxism worked its way into the political system. But the left was basically adrift in unfamiliar waters and the alliance with clerics caused internal schisms. the leftists were not sure how to manoeuvre politically or build the right institutions. They were mainly trained in writing manifestos and issuing class analyses. And in this case, Marxism got it all wrong: Religion was not just an apolitical opiate, it would not simply get kicked aside like a bad habit.

As the left analyzed, the clergy acted. Khomeini, already a popular figure, shrewdly built his support structures. In exile, he had mastered the trick of mixing modern tools with old structures. He famously sent recorded sermons down the pipeline of mosques and religious networks to reach millions of semi-literate Iranians. As provisional governments tried to build coalitions, Khomeini set up parallel groups of armed men, judicial councils and provincial representatives. These groups slowly purged the uncooperative. By the beginning of 1980, Khomeini was writing a new religious constitution and confidently calling the revolution “Islamic.” The left, like the rest of the world, fell into utter confusion. “Islamic revolution” was an oxymoron, a historical impossibility. Yet, like so many impossible things, it became a part of history.

One by one, leftist groups split, were persecuted and died away. By 1983, even the cooperative ones had been crushed. My aunt and Kianouri were jailed. A little later, Kianouri, visibly bruised and beaten, confessed on television that he had been a puppet of Soviet designs and reneged on all his ideals. He died under government surveillance in 1999.

My aunt was released from prison into house arrest soon after. When she came out, the Soviet Union and East Germany no longer existed, the Berlin Wall and Check Point Charlie had vanished, and everyone was using something called the Internet. She had been imprisoned in one kind of universe, then released into another. My brother who visited her in Tehran said she had trouble reconciling the two. She died under house arrest last year, but lives on at YouTube.

MY FAMILY LEFT IRAN at the end of 1978, two weeks after my thirteenth birthday. I experienced the actual revolution hunched over a small Grundig short wave radio in a foreign kitchen. Through phone calls to friends and family we got the skinny on imprisonments, confiscations and raids. My father, who was already seven years dead by then, absurdly appeared on the revolution’s wanted list. That list (a thousand names of families for some reason or other associated with the old regime) was originally concocted by leftists. Soon, those leftists found themselves on another, much longer list, and had to flee to places like Sweden and Canada.

One of them, a trained architect also called Ahmad, was a student in an English Second Language (ESL) class I taught. The ESL classes were organized by a left-leaning cultural centre that used to operate out of the basement of a warehouse building on Coloniale Street in Montreal. In the back of the Nima Centre—named after a poet—there were fading photocopies of newsletters and broadsheets issued by fragmented and bickering groups in Europe and North America, which nevertheless gave their publications titles like Solidarity and Unity. Moustachioed men hunched over ashtrays and leafed through them, swearing at the long Montreal winter. Inside their coat pockets, they kept their fists clenched. There was still talk of organizing, sending word back to Iran, protesting in front of the embassy. These were men who once directed marches, risked their lives for a better society, escaped prison with fingers missing, had friends hunted down and assassinated. Who could tell them it was all over? Who dared say it was all for nothing?

Clean-shaven, energetic and a non-smoker, Ahmad stood out. He too had been tortured in prison. He too escaped. It took two arrests and one imprisonment for him to decide to leave in 1984. The night Ahmad took off, for the border of Pakistan, he carried nothing but his architecture license and a roll of blueprints, which he’d secretly obtained from a friend, for a project near the border. He used these as cover, showing them to every soldier and guard as he fled through the countryside, up the mountains and over the border.

Five years on, having smuggled himself from Karachi to Montreal, he was still holding on to that tube of blueprints, as though they contained the outline of his own future. From the way he described them, it seemed that they had somehow kept him alive. Unbroken, he was determined to make a new life and was fighting to have his architecture license recognized in Canada, even as he drove a cab to make ends meet.

Why, I asked, did he wait so long to leave Iran?

“We had made the revolution,” he said, “and we thought we had to stick by it. It took us a long time to admit that the only rational option was to run.”

He described how hard they had struggled to understand the situation. Was this a bourgeois regime or a petit-bourgeois regime? A reactionary transition or a revolutionary moment? Were they to accept the lumpenproletariat as a revolutionary force? How about the religious proletariat? Every week, some group or other would attempt a new socio-historical analysis, and before the end of the week it would completely fall apart—first the analysis, then the group.

“It got to a point,” Ahmad told me, “that ‘History,’ ‘Progress,’ ‘Society’—all the big concepts of the 20th century—fell apart.”

Without a forward march, or a framework for understanding the world, individual survival became his only concern.

The sound of those concepts crashing to the ground—like statues pulled down in public squares, “cast, hollow and unsupported”, as Osip Mandelstam once wrote—is still ringing, and not just in Iran. No one can pretend anymore to know where History is headed, or design what Society ought to look like. No one can earnestly imagine humanity as a kind of fellowship, or propose for it a greater sense of purpose in the world. So for now, the only remaining ethos, as Ahmad pointed out, seems to be survival. There are other names for it—names ranging from “the free market” to “the selfish gene”—but that’s what it comes down to. Bare survival.

When last I saw Ahmad, the ex-architect and revolutionary was a draughtsman on payroll, his hair grey and thinning, back curled over a desk and an ashtray. He was touching up a redesign of a mall entrance for his corporate bosses. What the Islamic regime had not managed to break in him seemed to have been broken by a solitary and inconclusive career path.

For a moment, in the round patch of light slanting across the draughts of his blueprints, I saw the wheels of the other Ahmad’s overturned moped, still spinning aimlessly—over his head, and over ours.