Illustrations by Min Gyo Chung.

Illustrations by Min Gyo Chung.

Home Truths

In the Yukon, those with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder rarely find the care they need. Rhiannon Russell on a deadly lack of support.

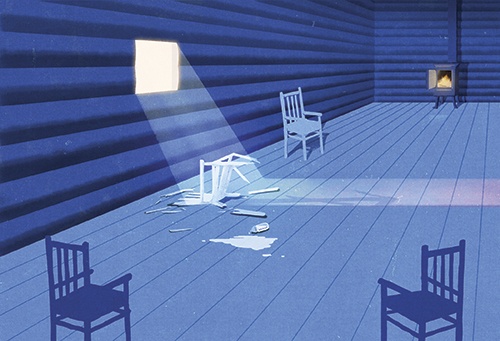

THERE IS AN AGING CABIN sitting on the outskirts of a town hours north of Whitehorse. The one-room building, surrounded by weeds and overgrown grass, is technically condemned. But there are signs of life: a ratty couch sags on the front porch; a black flag, emblazoned with a skull and crossbones, hangs in the window. Inside there is no running water, no bathroom and no electricity. In the winter, the temperature can drop to thirty-five below. This is where Eddie Brooks* calls home.

As a child, Brooks lived in group housing. Since then, he has bounced in and out of jail, prompting one judge to call him a nuisance offender. Now twenty-nine, he has racked up more than thirty convictions, for things such as assault, theft and resisting arrest. He struggles with anger management and alcoholism, which is common among those with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), a condition Brooks was diagnosed with early in his life. He is estranged from his family.

Brooks is not around when I drop by one Sunday afternoon. The front door is padlocked shut and he doesn’t have a phone. But his support worker, Wenda Bradley, says he is eager to see me.

Bradley worries about Brooks. In the past, she has arranged short-term hotel accommodations for him when he was released from the Whitehorse Correctional Centre but he always returns to the cabin, sometimes hitching a ride with staff at his First Nation. “It’s the only place there is for him,” says Bradley, executive director of the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Society Yukon (FASSY). “I can’t take him home. It is a struggle, because you know that if you were just available to him, things probably wouldn’t go wrong.”

Today, Brooks is on a court-ordered curfew, part of his probation for assaulting another man when he was drunk. For a while, he and Bradley had a system going: she would text him an hour before curfew and remind him that it was time to head home. That worked until he lost his phone. Brooks was then arrested once again, charged with violating his probation by breaching his curfew and drinking alcohol. “I think he’ll just go in and out of the system until either he does something drastic that keeps him in the system or someone comes up with an option,” Bradley tells me.

In the Yukon, Brooks’ options are lacking. Advocates say that supportive housing is the single best thing that society can do for those with FASD. Across the territory, though, this type of support is limited, contributing to a cycle of homelessness, criminal activity, untreated mental health issues and addictions.

FASD IS THE UMBRELLA TERM for a range of physical and cognitive disabilities caused by maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy. It covers everything from fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) to alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder and birth defects.

FASD is irreparable brain damage to a developing fetus. It affects people in different ways depending on when in utero they were exposed to alcohol and in what quantity. Physically, people with FAS may be small, with minute eyes, a thin upper lip and flattened mid-face. But many with the disability have no physical signs. They often, however, have behavioural ones. Impulsivity, hyperactivity, difficulty understanding the consequences of actions, poor memory, reduced motor skills, lack of impulse control and learning difficulties are all characteristics of the syndrome. Those with FASD struggle in academic and social settings. For children, this can mean acting out violently, failing grades and being manipulated and ostracized by peers. When they grow up, there can be more serious repercussions: difficulties finding and maintaining employment and housing, mental health issues and alcoholism.

Many adults with FASD have comprehension, maturity and social skills on par with those of a child—half have an IQ of less than seventy. However, this isn’t always apparent to those around them. People with FASD have good verbal communication skills and can parrot back what’s said to them, though they may not actually understand the meaning.

There is no data on FASD prevalence in Canada but FASSY Founder Judy Pakozdy believes that 250 people with the disability live in Whitehorse alone. A Public Health Agency of Canada estimate puts the rate at roughly 1 percent of the population, or nine births per one thousand, but those numbers are thought to be higher in isolated northern communities—a 1985 survey in the Yukon estimated the rate of FAS in aboriginal children was forty-six per one thousand.

Yet, as a 2005 article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal states, it’s a common misconception that FAS is linked to ethno-cultural background. Risk factors for prenatal alcohol exposure include lower education level in women, lower socioeconomic status, inadequate nutrition and poor access to pre- and post-natal care. A five-year study of mothers of children with FAS found they came from diverse racial and economic backgrounds and typically had mental health issues, faced social isolation and experienced severe sexual abuse as children. Because of their symptoms, many with FASD require a high level of support and structure, either from family members or support workers, in order to complete day-to-day activities. They may need help finding a place to live, getting up on time in the mornings, cleaning, cooking and paying bills. However, they don’t often have it. “By the time they get to adults they are often alienated or have exhausted their caregivers, so they are out on their own,” Dr. Sterling Clarren explained at a 2008 FASD conference in Whitehorse.

Because of this high level of need, a typical house or apartment often won’t do. What many require is supportive housing: an affordable space that offers services to help them live more stable lives. But there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Supportive housing may mean a group home. It may mean living with a helper. Or it could mean having a support worker drop by every few days or once a week to help with specific tasks. Matching the type of support to the person can make all the difference. “Often we tell people that they’ve got to get their lives together before they can find some sort of suitable housing. But quite often, housing itself is the intervention that’s really needed,” says Dr. Amy Salmon, executive director of the Canada FASD Research Network.

IN 2010, ROBIN SAM was found not criminally responsible (NCR) for aggravated assault. The judge cited in part the “cognitive deterioration” he experienced as a result of likely prenatal exposure to alcohol. He spent six months on remand at the jail in Whitehorse and eventually pleaded guilty. Because of the NCR finding, Sam had a treatment team tasked with ensuring he was properly counselled and supported. He did well for about three years after his release: he was living in his home community of Pelly Crossing, taking his anti-seizure medication and working for the Selkirk First Nation, tending to the fires that heat government buildings in the winter. But somewhere along the way, things started to fall apart. Sam stopped taking his medication and though he told his support team, they never alerted the board tasked with monitoring those found NCR. At a check-in with the board in January 2014, Sam was reportedly disoriented, frightened, moaning and rocking back and forth. He left the meeting and, three days later, was found dead in the snow beside a busy thoroughfare in Whitehorse. In the twenty-six-below weather, Sam was wearing a black hoodie, camo pants and his right shoe.

When support systems are absent, many people with FASD wind up on the streets and engaging in criminal behaviour. Most of FASSY’s thirty-seven clients have been involved in the criminal justice system, either as victims or offenders. Jail can be a revolving door; because of their brain injury, many with FASD can’t learn from their mistakes, leading to repeat offences. Typically, the crimes are alcohol-fuelled and done in an attempt to feed addictions.

One Pelly Crossing man with severe FASD managed to avoid run-ins with the law as he was growing up in his grandparents’ home. But when his grandfather died, his grandmother moved into a care facility. Without structure and stability, the man, who has the mental capacity of an eight-year-old, started to get into trouble. He racked up about fifty convictions by the time he was thirty-five, including some for sexual assault. He now lives at a supportive group home in Whitehorse specifically for people with FASD. Since moving in, he’s had no further involvement with the justice system.

Robert McLaughlin,* another repeat offender, told an FAS assessment team that he didn’t mind being in jail: he feels safe there, the rules are simple and his days are structured. Both his parents were taken to residential schools as children, subjected to physical and sexual abuse and later struggled with alcoholism. His mother drank while pregnant with all four of her children. When sentencing McLaughlin for armed robbery in 2011, a judge referred to a psychological assessment that found the then-twenty-six-year-old did not have the capacity to live independently. If he doesn’t get the necessary support, he’ll reoffend, the judge said, adding that McLaughlin’s probation officer, FASSY, Yukon’s Health and Social Services, his First Nation and his family must prepare a treatment plan before his release from jail. That never happened. But at first, things were looking up: McLaughlin returned to his home community and completed a training program for heavy equipment operation. But when his relationship with his son’s mother ended in 2013, he started drinking heavily and committed another robbery, sending him back to jail. In April, McLaughlin was arrested again. He is now facing a string of new charges: robbery, assaulting a police officer and resisting arrest.

A report on the 2008 FASD conference in Whitehorse states that people working in the courts need to better understand those with the condition and a stronger effort is required to stop the cycle of incarceration. “The justice system [should not be] used as a substitute for appropriate social services and supports for some of the most vulnerable citizens,” argues attendee Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, British Columbia’s representative for children and youth.

A RAINBOW OF PAINTED HANDPRINTS greets visitors to Options for Independence (OFI) in Whitehorse, the names of its fourteen residents written underneath each one. I am here to see two of those residents: Teddy Jackson and Martina O’Brien.

The husband and wife were evicted from a previous OFI home in May 2005 due to their violent behaviour towards staff and other residents. The territorial government relocated them to a subsidized house in a Whitehorse subdivision where support workers dropped in regularly, but Jackson and O’Brien became hermits, hoarding televisions, DVDs and VCRs that they acquired at garage sales and pawn shops. They barricaded the front door to keep support staff from getting in and threw tantrums when the mail carrier arrived without their social assistance cheques. Broken windows went unfixed. Piles of junk grew. Their home became a safety hazard. The government eventually moved them back downtown into a duplex with support workers from the Options for Independence Society dropping by daily or every other day to help them clean and drive them to their jobs: Jackson’s at Walmart and O’Brien’s at an organization for people with disabilities. But the couple’s living situation did not improve. Jackson and O’Brien had raging fights and verbally abused the staff, who quit regularly. The couple has four children under the age of thirteen, but all of them were taken out of their custody right after birth.

A staff worker at OFI calls up to Jackson’s one-bedroom suite and the man who comes down greets me with a big grin. At thirty-eight, Jackson is short and wiry. His skinny wrists peek through when he pushes up the sleeves of his black Jack Skellington hoodie that’s at least two sizes too big. He remembers the day he moved into his current apartment at the new OFI complex in March 2014. The door had a sign with his name on it. He felt like he was home. “Finally I got a place for me and Martina,” he says. “It’s a lot easier than staying out on the street. I like it here.”

OFI’s new residence, run by the non-profit Options for Independence Society, opened last year with funding from federal and territorial governments. Also known by its First Nations name Dun Kenji Ku, which means People’s Place, OFI offers those with FASD a safe, secure and supported space to call home at a cost of up to $1,200 per month. It is lauded as a pioneer housing project by FASD workers and advocates. Staff are on the premises day and night to ensure Jackson, O’Brien and other residents wake up on time for medical appointments, eat, shower and take their prescribed medications. They help them with grocery shopping, drive them to the pool to swim and intervene if a crisis arises. The staff try to see residents on a daily basis and if they haven’t seen someone for a day or two, they will knock on the door to check in.

But OFI is a home. Residents can come and go as they please. Each has a key to the front door. “I think the level of privacy and freedom, and individual choice and autonomy, residents have here is what makes it not an institutional environment,” says Colette Acheson, an OFI board member and the executive director of the Yukon Association for Community Living. Acheson says that this differs from other types of facilities; she worked at a group home in Alberta where meals were at set times every day. “You’d all eat macaroni and cheese if that was on the menu for tonight, whether you like it or not,” she says.

OFI also acts as a buffer between the residents and the police. Building Manager Sam Mutiwekuziwa says if a resident gets drunk and belligerent, calling the RCMP is a last resort. Support workers will try to defuse situations instead of escalating them. But sometimes calling police is a necessity. Usually, the RCMP will put the resident in the drunk tank overnight. Charges are rarely laid. The resident returns home the next day, sober. “No hard feelings, no grudges,” says Mutiwekuziwa. He is proud that OFI has reduced the involvement of emergency responders in the lives of the people who live there. With two workers on shift at all times, residents also have someone to speak with whenever they need.

Mutiwekuziwa says that Jackson and O’Brien have become stable since moving into the building. He thinks the change comes down to creating a more tailored form of support for them; staff realized they had to give the couple a little more autonomy, which made Jackson and O’Brien less stressed. They still have their bad days, but they happen less often. Fortunately, neither struggles with alcoholism or criminal activity. Jackson plays soccer for the Yukon’s Special Olympics team and has a part-time job cleaning up garbage along the waterfront. Staff even arrange for the couple’s children to come together with their respective foster parents for visits.

The building is not OFI’s first experiment with FASD housing. A sixplex opened more than ten years ago, offering, at first, only part-time support to residents. “So many of them [people with FASD] were falling by the wayside: dying, freezing in the back of pickup trucks in the winter, stuff like that,” says FASSY’s Pakozdy. “We knew that they needed somewhere to live as adults.” But it still wasn’t enough. When the new, larger OFI residence opened featuring day-and-night support, the sixplex shut down and the residents all moved in. An admissions committee made up of OFI board members and Health and Social Services selected another eight people. Prospective residents had to be adults, either with diagnosed or suspected FASD, and have a minimal criminal record.

When the building opened, twenty-seven people applied for the eight available spots. “That’s quite a disparity,” Mutiwekuziwa says. “We knew that we were going to leave out people who would need accommodations.” And since FASD is a lifelong disability, the building’s current waiting list of fifteen names is not budging. At this point, the Yukon Housing Corporation and the Department of Health and Social Services have no firm plans for future FASD residences. None currently exist in the Yukon’s small communities and the government’s supported-living program, which sees workers assist people who have disabilities with basic life tasks, isn’t offered outside of Whitehorse. If two more group homes like OFI were to open in the territory today, FASSY’s Bradley says that they would immediately be full.

Having a range of housing options for people with FASD is essential, because the needs of those with FASD vary from person to person. A therapeutic-roommate model has seen success in Alberta; someone shares an apartment with a person who has FASD and, in exchange for helping them plan their schedule and learn basic life skills, pays reduced rent. Another option, similar to a foster home, aims to keep children with their FASD-afflicted parents. These arrangements, called proctor homes, see the parent and his or her children move in with another family in the community. The original residents are taught about FASD in advance and trained in parenting, as well as processing and behavioural issues. The host family receives payment for their efforts and assists the mother or father in caring for their children and themselves. “People are parenting by being shown and some people’s challenges are such that they need to be shown on a daily basis and their children need to benefit from the safety that that will provide,” says Suzie Kuerschner, a FASD consultant who has worked across North America.

A now-extinct three-year program in Victoria, British Columbia, put new mothers with FASD into homes with their babies along with an adult or family filling the role of foster parent. It was very successful, Dr. Amy Salmon recalls. Most of the women were able to keep custody of their children. But then the funding ran out.

FASSY FOUNDER JUDY PAKOZDY met Matthew when he was one. It was February 1980 and she had flown from Whitehorse to his foster parents’ house in Yellowknife. She remembers his thick black hair and dark eyes. “[He was a] gorgeous little kid,” she says, recalling how he scooted and bounced around the floor. “Happy as shit.”

Matthew had been diagnosed with FAS at birth. So had his seven siblings. Pakozdy, a pediatric nurse, decided to adopt him. With her education and training, she thought she could cure him. She brought him home to raise him as a single mother and that was the start of what she describes as “a very horrible life” both for her and Matthew. “People want to believe they can make it better, and you can’t fix brain damage,” she says. “It takes a lot of work for you to realize how hard it is for them to figure out the world.”

I meet Pakozdy, now seventy-three, in Carcross, a picturesque village an hour south of Whitehorse. She used to be a my-way-or-the-highway type of person. But that didn’t work with Matthew. He didn’t walk until he was seventeen months—a blessing that Pakozdy didn’t realize at the time. After that, he was always on the go: running out of the house and disappearing. He was hyper and impulsive. Matthew had a passion for singing and dancing, so Pakozdy entered him in up to ten dance classes a week starting in elementary school. It gave her a break. After dropping him off, she would lie down in the school’s hallway and sleep for an hour. It also allowed Matthew to burn off some of his excess energy. “It worked for both of us,” she says with a laugh.

But Matthew’s teen years were rough. He had angry outbursts, kicked holes in the walls and slammed doors so hard they broke off their hinges. He twice broke a phone over Pakozdy’s head when she was trying to call for help. She still has scars on her arms from attacks. Whenever Matthew was frustrated or scared, or when he realized he had hurt his mom, he would take off on his bike. Sometimes he would go to a nearby cemetery, halfway up the side of the mountain in their neighbourhood, and visit the graves of people he knew. But most of the time Pakozdy had no idea where Matthew went. She would spend hours driving around, searching. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” she says. “I didn’t understand what his behaviours were from.” One night, after a particularly bad fight, she called his social worker and told her to pick up Matthew. The adoption was over, she said. The social worker just laughed. “It was that night that we sort of hit the wall and I said to him, ‘Nobody’s going to help us here. We’re lost, and we’re going to kill each other or we’re going to have to figure it out ourselves,’” Pakozdy says.

In high school, Matthew joined a performing arts program that Pakozdy credits with saving his life. He didn’t have many friends—the other kids would go off and eat lunch together without him—but that didn’t seem to bother him. When a concerned Pakozdy asked what he did on his own, he replied, “Mum, as soon as they go, I turn on my boombox and I dance!” At nineteen, Matthew was accepted into the Canadian College of Performing Arts in Victoria, BC. Pakozdy helped him get set up in Victoria with a support worker. He still lives there to this day.

When I call Matthew, he greets me warmly. He’s immediately likeable, bubbly and chatty. Now thirty-five, he works part-time at an aboriginal housing society and is training to become a Zumba instructor. He adopted Maggie, a boxer dog that he takes for walks along the beaches every morning, and goes to yoga classes on the weekends. Matthew lives in a townhouse with a full-time support worker. Three other support staff, women he calls his “angels,” are on-call to help him with groceries, taxes, going to the gym and cooking. “I think that if I didn’t move out of the Yukon, I wouldn’t have gotten as much support as I’ve gotten here,” he says. “Because of that, I’ve grown immensely.”

Matthew was in his twenties before he fully grasped what having FAS meant. When he was a child, he didn’t understand why he was being scolded, why he was held back a grade when all his classmates advanced. As a young adult, he struggled with understanding why it was so difficult to maintain relationships and jobs. “It’s a very exhausting life,” Matthew says. “I can’t just switch it off tomorrow and be like, ‘I’m normal! Awesome, cool, great! I can live a great life now.’ I am living a great life, I just have to work harder every day with what I’m doing.”

Matthew, with his development and abilities, is a miracle, Pakozdy says. She credits the full-time, live-in support—paid for by the BC government—as being crucial to his success. Whenever he has a crisis, there is someone there to help. If Matthew were to live in close quarters with people higher on the FASD spectrum than him, Pakozdy thinks that he wouldn’t do well.

Matthew’s case isn’t the typical story of someone with FASD. Pakozdy was there fighting for him at the pivotal moments of his life: founding FASSY, speaking up at conferences, arguing with teachers. And it paid off. Matthew now has a proper support network, she says. He has a future.

IN THE YUKON, Matthew’s options would be limited. There is the OFI residence, government housing, or private housing with assistance from either FASSY or the Department of Health and Social Services’ supported independent living (SIL) workers. There are no proctor homes or therapeutic-roommate programs in the territory.

FASSY has seventeen people on its waiting list for support. And while the Yukon government has eight SIL workers who assist people with disabilities, the Yukon Anti-Poverty Coalition’s 2011 report found that this doesn’t meet the demand. It called on the government to hire more of these workers.

While OFI is a unique concept—it has received many visitors from FASD agencies across the country looking into its model—everyone I speak with says that it just isn’t enough. Pakozdy calls it a drop in the bucket: “If we don’t address it, more and more will die. Or they’ll go to jail.”

Yet Pakozdy is optimistic that the Yukon government will increase housing options after seeing OFI’s success, and expects another group home will open in Whitehorse in the future. She also hopes for housing in Dawson City and Haines Junction, two of the Yukon’s larger communities. But those living in rural areas will still struggle to access help. Services such as FASSY and SIL workers are more easily accessible in Whitehorse, often leaving affected people in the more isolated communities without adequate support.

People like Eddie Brooks.

It takes me three months to finally connect with him. I stick a note under his front door as I drive through his town one day, and by this point, he’s gotten a cellphone and texts me that night. We exchange messages but whenever I try to talk with him live there is an issue: he has to work, his phone is dying or running out of minutes, he drops off when trying to arrange a time.

I text him one Monday and ask how his weekend was. There is no response. On Wednesday morning, at my job as a newspaper court reporter in Whitehorse, I see his name on the docket again. He’s back in custody, facing new charges of breaching his probation and possessing drugs. When I am finally able to meet Brooks face to face, it’s in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre visiting room.

He greets me politely with a handshake, a black skull tattoo on his left forearm. We chat about jail. He hates it. He spends his time watching movies on the TV in his cell, playing cards with other inmates and attending a men’s group for alcohol addiction.

I ask Brooks about his cabin. “It’s not much,” he says sheepishly. He used to live with his dad but “I flipped out on him and got the cops called on me ... so I took off.” The cabin was empty and abandoned so Brooks moved in.

When I inquire about OFI, whether he thinks it could be a good environment for him, he seems unimpressed. “I’ve been through a group home all my fucking life and I don’t want to get into that shit again,” he says.

So, I say, if he could live anywhere, where would it be?

Brooks would stay in the town north of Whitehorse. He’s got family and friends there. It’s home. “But in an up- to-date house. Just a regular house. A good house. Livable and comfortable.”

I nod and tell him that it doesn’t seem like too much to ask for.

*Name has been changed.