Photograph by Eva Holland.

Photograph by Eva Holland.

The Forgotten Internment

When World War II threatened a remote chain of islands off the Alaskan coast, the indigenous Aleut people were displaced from their homes.

All of the survivors remember the trees. The towering hemlocks and the Sitka spruce; the scrubby shore pines and the leafy alders. "I used to look at them in school books," a woman recalled, seventy-one years after she first saw them. She'd found the trees interesting, in the books. But she felt trapped once she stood beneath their branches.

She had come—they had all come—from their treeless islands, against their will, to this rainy slice of dense, damp forest, wedged between mountains and ocean. The Second World War had stormed the Aleutians, a far-flung string of islands off Alaska’s southwestern coast. Japanese bombs had fallen on Dutch Harbor, and Japanese troops occupied the westernmost islands in the chain. And so the United States government had brought their native occupants, the Aleuts, here, to a handful of makeshift camps in the coastal rainforest of the Alaskan panhandle, to wait out the inferno. The trees, more than anything else, represented the strangeness and terror of their sudden relocation.

The evacuation was prompted partly by a sense of paternal benevolence and responsibility but was conditioned by racist attitudes. It would result in three years of suffering and the death of more than a tenth of the Aleuts in the camps. Afterwards, life on the islands would never quite revert back to its previous stability: alcoholism would take hold and some villages would never be repopulated. It would be decades before the haunted survivors told their stories.

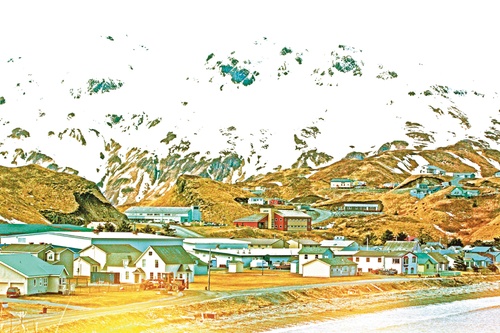

ON THE SOUTHWESTERN COAST of Alaska, a long peninsula stretches out into the vast Pacific Ocean and forms the southern boundary of the Bering Sea. Off its tip, an arc of islands runs further west yet—its westernmost outpost, Attu, lies just over a thousand kilometres from Japan. The remote, volcanic Aleutian Islands have been home to the Aleuts (or the Unangan—meaning “the people”—as many now call themselves) for thousands of years. The Aleutian Islands are bald humps that rise dramatically out of the pacific in a scattered chain around 2,000 kilometres long: treeless, with volcanic peaks that top out nearly 3,000 metres above sea level, they look like rolling alpine meadows that descend abruptly into the ocean. For centuries, the Aleuts’ daily activities revolved around the water: they fished and hunted in baidarkas, lean traditional kayaks most often made from the hides of sea lions. The ocean provided them with an abundance of whales, seals, salmon, halibut and shellfish; the islands also attracted an annual migration of millions of birds. Even today, bald eagles lounge on lampposts and roam the streets of Unalaska, the Aleutians’ largest town, common as gulls.

Unlike many neighbouring indigenous groups in Siberia and mainland Alaska, the Aleuts remained isolated until the arrival of the first Russian explorers in 1741. The discovery of the islands’ rich sea otter population prompted a mad rush for furs and, eventually, a bloody Russian conquest and colonization. A decimated Aleut population, reduced by as much as 80 or 90 percent, was solidly converted to Russian Orthodoxy by the time the Alaskan territory was sold to the United States for $7.2 million in 1867. The church became the centre of Aleut life.

The people, who had long since adopted Russian surnames, placed gold-leaf icons and relics in their churches and attended school in Russian and Aleut—an Orthodox priest had created an alphabet for their native language early in the nineteenth century. (The United States would eventually place restrictions on the use of both Russian and Aleut in the islands, and Methodist missionaries would arrive hoping to re-convert the converts, with limited success.) They lived a kind of hybrid life: seeking subsistence from the sea while readily adopting modern conveniences like plumbing, electric light and range stoves, despite their isolation.

UNDER AMERICAN RULE, the several hundred remaining Aleut people were classed as “wards” of the state. Residents of the islands St. George and St. Paul—north of the main Aleutian chain, where the rich seal hunt took place—were overseen by the Fish and Wildlife Service. The rest of the Aleut communities fell under the purview of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs and its subsidiary, the Alaska Indian Service. When war loomed with Japan in the 1930s, the Aleuts’ fate was in the hands of an array of overlapping government departments.

The bureaucracy was tangled even further in 1940 and 1941, when the US military, seeing the Aleutians as both a possible enemy target and a potential launching point for an American attack on Japan, initiated a military buildup in the islands. Dutch Harbor—the military and marine facility adjacent to the civilian town of Unalaska—was the hub of the new activity. Soldiers and labourers flooded in from outside, property values rose and liquor flowed. On December 2, 1941, just days before the attack on Pearl Harbor, frustrated federal officials handed civilian administration of the town over to the military authorities.

On December 7, hundreds of Japanese fighter and bomber planes struck in Hawaii. By the next morning, four US battleships sat at the bottom of Pearl Harbor and more than 2,000 Americans were dead. The United States was at war and the Japanese enemy, military strategists knew, would be eyeballing the Aleutians.

With the area now a potential war zone, various civilian and military players hemmed and hawed over the possibility of removing the Aleuts from their islands. The confusion is documented in intricate detail by Dean Kohlhoff in his book, When the Wind Was a River: Aleut Evacuation in World War II. If there were serious casualties among Aleut civilians, it would leave administrators open to criticism, of course, and it would be easier for the military to operate without a population of “wards” underfoot. But a mass civilian evacuation was a daunting logistical prospect and no one knew how far the war might spread. With so many different government entities having a hand in the management of the Aleuts, no one agency was inclined to take the lead on a possible relocation.

“As a consequence,” Kohlhoff wrote, “no chief planner was designated to determine whether evacuation was necessary. If it were, there was nobody to decide which Aleuts were in greater danger and should be evacuated first. Nobody was appointed to prepare relocation facilities.” By the time the bombs began falling on Dutch Harbor, on June 3, 1942, no logistics for a relocation had been developed.

THE BLACKOUT RULES imposed in the lead-up to the first attack on the islands form Harriet Hope’s earliest memories. The youngest child of an Aleut mother and a white father, Hope was five, going on six. “If there was a speck of light, you got yelled at,” she recalls, sitting at the dining room table in her small apartment in the Unalaska seniors’ centre. She remembers the sirens, too, that sent her family scurrying to crude dugouts near the creek, unsure if, this time, it was just another drill.

From her window, today, Hope can see the embankment where she and her family took shelter. “That’s where we went,” she said, leading me to the glass and pointing. The grassy slope loomed larger in her childhood memory than it looked now to her adult eye. The recalled smell of fresh-dug earth is still vivid, she said. When the Japanese planes came, she remembered bouncing from the house to the dugout and up into the hills outside town, sticking close to her family while the smell of smoke hung in the air and a fuel cache down by the bombed-out docks burned and burned.

The attack on Dutch Harbor lasted for two days. Then, on June 7, over 1,300 kilometres away at the far end of the Aleutian chain, the Japanese invasion of Attu and Kiska began. On Attu, the lone Bureau of Indian Affairs bureaucrat was executed and the forty-two Aleut residents were rounded up; they would eventually be shipped to Japan, as prisoners of war, where more than half of them would die of starvation and tuberculosis before the end of the fighting. There were no civilians on Kiska, just a ten-man weather-monitoring team from the US Navy—they, too, were captured and sent to Japan.

The invasion triggered the chaotic removal of all the Aleut civilians from the islands. On June 12, a naval commander ordered the immediate evacuation of Atka, the next-most-westerly Aleut settlement, 875 kilometres east of Attu. Once its residents had retreated to the hills, they watched as a military crew burned the village to the ground to prevent its use by the invaders. Then the Atkans were ordered to board a military ship and, without further explanation, their long voyage east began.

Over the next month, the remaining nine Aleut settlements were emptied and their buildings, instead of being burned, were occupied for military use. Residents received little to no warning of their departure and no information about where they were going or how long they would be gone. Some were allowed to bring a single suitcase each; others carried nothing at all.

Sergius (Sergie) Krukoff, then a ten-year-old boy from the village of Nikolski, recalled being shipped to Unalaska on a terrifying nighttime voyage. “They put us on the barge,” he told me. “that day the wind was blowing, no lights, everything was dark on the barge. During the war they didn’t have no lights on those boats at night, eh? Because the Japanese would see you.” His clearest memory of his arrival in Unalaska is seeing the fiery hulk of a ship lying on the night-dark beach, still burning from the Japanese bombs. “Then they put us on the ship and they took off again. We didn’t know where they were taking us. At least they were feeding us, that was the main thing.” He spent seven days on board the SS Columbia with 159 other Aleuts, the collected residents of six far-flung villages. The voyage was punctuated by warning sirens and drills, Krukoff recalled, and a looming fear of the Japanese enemy.

Hope, her mother and three of her siblings sailed with 106 other Aleuts from Unalaska. The settlement was the only one with a substantial white population, and those residents—including Hope’s father, the postmaster—were not a part of the evacuation. Hope remembered seeing him standing on the beach in front of their house, “waving frantically” as his family receded towards the horizon. Over the coming weeks and months, Hope told me, her father would seek answers about his wife and children. “Trying and trying, calling everybody, writing to Washington, DC, trying to find out—nobody would tell anybody what the plan was. It was like being part of a huge secret.”

Andronik P. Kashevaroff and Ella Kashevarof, now a married couple in their eighties, were fourteen and fifteen when they were evacuated from their homes on St. George in the Pribilof Islands.

The couple carries hard memories from the trip. Today, they split their time between St. George and their daughter’s house in Anchorage, on the mainland. I met them there, and listened while they took turns, with the easy comfort of decades spent together, telling me about their war years.

“That boat was loaded up,” said Kashevaroff. “Everything was just crowded. Crowded.”

“They put us in that, what you call that in a ship? Open area?” Kashevarof asked.

“Hatch. Cargo hatch,” he replied.

“Hatch. Even old sick people from St. George, they put them in there. Very draughty.”

“Cold.” Kashevaroff again.

“Cold,” his wife agreed.

“I guess there was no more room on this ship, no more bunks,” he offered.

“No privacy, nothing. Just like animals,” she said.

Kashevaroff looked up from his memories then, looked right at me, and spoke firmly.

“She’s right. My wife is right. We were treated like animals.”

CONDITIONS WERE NO BETTER when the Aleuts arrived at the hastily-located internment camps. Meals were basic; medical supplies were limited and medical staff largely absent; sanitation was nonexistent. Tuberculosis, the flu, measles and pneumonia thrived. One site, Ward Lake, would see an 18 percent rate of fatality among its internees. Of the 831 Aleuts relocated to Southeast Alaska, eighty-five would die in the camps.

The Pribilovian Aleuts were taken to two camps on opposing sides of Funter Bay, near the state capital of Juneau—the people from St. Paul went to an abandoned cannery, and those from St. George to a one-time gold mine. The residents of Atka were sent to Killisnoo, a defunct herring factory a short sail south of Funter Bay.

For the bunkhouses, there were honey buckets. For a group of nearly two hundred people, there was one outhouse on the beach that relied on the surf to clear the human waste away. Drinking water was the colour of tea. The bunkhouses were built above the tidal waters of the bay and the Aleuts could hear the waves rolling in and out below them.

Aleuts who were able to find work in town were allowed to do so, in part to relieve the camps’ overcrowding. Young Kashevaroff made his way to Juneau for much of the first year of the internment. His parents, unwilling to sit and rot in the camp, found jobs there, and rental housing that was far superior to the bunkhouse at Funter Bay. Kashevaroff got a job at a café, and then—in an ironic turn—at the governor’s mansion, mowing the lawn, vacuuming and doing other household tasks.

“Before evacuation we didn’t have any liquor store or bars,” Kashevaroff told me. “But when we got to Juneau you start seeing signs—open liquor, open liquor. And bottles in the liquor store, all in the windows. there’s where people started getting liquor from.”

“More and more people started drinking?” his daughter, Bonnie, asked.

“Yeah,” said Ella Kashevarof. “They learned.”

In September 1942, Kashevarof and some of the other young girls were taken to the Wrangell Institute, a native boarding school further south. There, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and was moved again, to a Ketchikan hospital for six months of treatment. She recovered from the illness, but her family was afraid to send her back to Wrangell for her sophomore year. “My dad said ‘No, you’re not going back, you’re going to get sick again.’ So I didn’t go back to high school.” She would wait out the remainder of the internment in Funter Bay with her family.

While the Pribilovians settled in at Funter Bay, the rest of the Aleuts—the residents of Unalaska and the more easterly Aleutian villages—were shipped to the Wrangell Institute. Some filled the dorms, while the overflow lived in tents for the summer on the boarding school’s grounds. As Sergie Krukoff recalled, “Only time we go into the building is when we’re going to have breakfast, lunch or dinner, or bathroom. Other than that, after you get done with what you’re supposed to do in the building, you have to go back to your tent.” Then he shrugged, fatalistic. “It was okay.”

By the time the 1942 fall semester had begun the Aleuts had been moved once again: the Unalaskans to a burned-down cannery at Burnett Inlet and the collected residents of six villages to a former federal work camp at Ward Lake. Krukoff remembered the villagers sleeping together on the floor in a large mess hall after their arrival. They ate their meals there, too. there was a makeshift church—nothing like the grand Russian Orthodox cathedral down the street from his home in Unalaska today, he pointed out. “But we put a few icons up, candles.”

He remembered being afraid of the grizzly bears that are commonplace in Southeast Alaska—there are none in the Aleutian chain—and missing the sound and feel of the wind that he’d grown so used to in the islands. He remembered a swimming pool near the camp. “We weren’t allowed to go there. White people only.” And he remembered the daily shuttle buses that would take the Aleuts into nearby Ketchikan: for work, for those who had found jobs in town, or to see a movie, or to buy some liquor. That was the one problem with the jobs and the money to be found in town, he said. The Ward Lake camp was home to Aleuts from six different villages, some with different traditions and dialects. “When they start feeling their drinks, they don’t like each other, and the fights start,” he said. “I used to hide under the building and watch people fighting.”

Mostly, Krukoff recalled playing with the other children in the strange, looming forest around the camp. “We played hide-and-go-seek, that was a good thing to do in trees,” he told me. “When we started playing we’d forget about the bears.” But he was always aware of Ward Lake’s grim realities. “The Father and the choir would go out in those trees before they buried people, singing dead people songs.”

THERE WERE VALID REASONS for evacuating the Aleuts. The Japanese could keep coming east, after all, and the military would prefer to fight them without risk of massive civilian collateral damage. But there was more to the decision than pure pragmatism—or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that military practicalities might not have been sufficient motivation to forcibly remove a population of white US citizens from their homes. As Dean Kohlhoff pointed out in his book, the Aleuts were evacuated after the attack on Dutch Harbor had already passed. The Japanese would never again push east of Kiska. And the non-Aleut residents had been permitted to stay, despite the possible danger. “Racial discrimination,” not safety, Kohlhoff wrote, was “an underlying motive in the convoluted Aleut removal,” something the government would make perfectly clear before the war was over.

In the spring of 1943, Andronik Kashevaroff was called back from Juneau to Funter Bay to gather with the rest of the Pribilovians. The annual government seal hunt in the Pribilof Islands was a million-dollar operation, and the men of St. Paul and St. George were needed to pull it off—though many of the hunters were not yet “men” at all. “I was just a kid. Fourteen,” Kashevaroff said. “We were in the war zone.” The internees balked at returning for the spring hunt. They had been told that their jarring relocation and internment had been a necessity, for their own safety. How was it safe for them to return home to hunt, but not to live at home with their families? To the American government, the profits of the seal hunt outweighed the potential danger.

The Fish and Wildlife Service—of whom the Pribilovians remained legal wards—declared that any Aleut who refused to return for the seal hunt when called upon would be barred from ever returning home after the war. “Disobedient Aleuts,” a superintendent declared, would permanently lose “all privileges as an island resident.” The seal harvest went ahead as planned.

THE US MILITARY and its Canadian allies had retaken Attu by the end of May 1943, and Kiska by August. But it wasn’t until the spring of 1944 that the surviving residents of St. Paul and St. George were allowed to return home from Funter Bay. A year later, in April 1945, the residents of Unalaska, Atka and the rest of the Aleutian villages followed. At home, many found their houses ransacked by the now-departed soldiers and civilian contractors, their possessions scattered and destroyed. On Atka, where the village had been burned during the evacuation, they came home to no houses at all.

Three groups of internees—the residents of Makushin, Biorka and Kashega— were never permitted to reclaim their small villages. The remaining handful of Aleuts from Attu, who’d survived the years in Japan and finally made it back to Alaska in december 1945, were likewise barred from returning to their island. The cost of restoring the damaged and destroyed settlements was too great, the government said.

For decades after the end of the war, the evacuation and internment were rarely spoken about. “It was buried,” Harriet Hope recalled. “You don’t talk about it. You don’t whine, you don’t complain. It must be the right thing because the government ordered us to do it that way. that was my feeling, anyway.” But nobody had forgotten. And in the 1960s and 1970s, as a handful of new Aleut political organizations grew and gathered strength, so too did the idea of seeking redress and reparations.

In 1980, US president Jimmy Carter signed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians Act; it was intended to address the Japanese-American internment of the same era, but political allies of the Aleuts were able to get its mandate amended to include the Aleutian evacuation and internment, too. In 1981, the remaining survivors of the camps began to share their stories. Some spoke in person at hearings in Anchorage, Unalaska and St. Paul; others completed written depositions. In all, nearly two hundred testimonies were collected.

There is a grim, spare poetry to the depositions:

By what means were you taken from your village?

“War.”

Which members of your family were taken with you?

“Mother. Father. Sister. Brother.”

How much notice did they give you before you left home?

“None.”

What were you allowed to take with you?

“Clothing in a pillow sack.”

List all personal property you had to leave behind.

“House with everything in it.”

How were the quarters to which you were taken?

“Crowded, cold, damp.”

List to the best of your knowledge anyone who died while you were at the camp and where they were buried.

“My brother died at Juneau, and was buried there. My father at Killisnoo.”

List any other facts about your stay at the camp and your return home and after you got home.

“We were happy to come home, but we came home to nothing.”

What was destroyed or missing?

“My house and everything in it.”

What would you like to have done in your community as a memorial to those who have died since the evacuation?

“Pray for them. Always.”

“I THINK ABOUT IT ONCE IN A WHILE,” Andronik Kashevaroff told me that morning at his daughter’s kitchen table in the suburbs of Anchorage.

“Me too,” said Ella Kashevarof. “We talk about it.”

“We talk to each other, we say, ‘Remember, that’s how it was.’”

“It changes you,” Kashevarof said.

“It changes you,” her husband echoed.

“Back home it wasn’t like that. Quiet life we had before World War II. And we were thinking how people could treat each other like that, you know?” Sometimes, Kashevaroff said, his memories of Funter Bay rise up unbidden. “It just comes to you like that. How would you say it? It just comes to you, and you start thinking like that.”

Talking, his wife said, “helps some. It’s good to take it out of your system and all that.”

“If you tell the truth, it’s very important,” he said. “You gotta speak it out.”

On Unalaska, Sergie Krukoff, too, finds his memories of the internment surfacing unexpectedly. He’s a small, brown-eyed man with a buzz cut and a small patch of white whiskers on his chin, and both his legs have been amputated above the knee. When I met him, he wore bifocals and a pair of plastic headphones connected to a hearing aid and rolled around his small house in a wheelchair.

He traces a changed, and shrinking, Aleut culture to the internment years. “Things that [Aleuts] used to be doing, Aleut games they used to have, they don’t do it anymore. People that used to do them, they’re all gone. they died. But we didn’t learn enough.”

“Before the war, everybody used to talk Aleut. Down in Southeast that’s when people started talking English, and now ...” He trailed off. “I went to the Aleut school in Nikolski, that’s why I never forget my own language. I still talk Aleut, if I meet somebody I know that can talk with me.”

There are fewer and fewer native Aleut speakers, though, and fewer and fewer internment survivors—perhaps two dozen, at most, scattered across the islands and the mainland. Patty Lekanoff-Gregory, the grown child of one Unalaskan survivor, had told me that every year at the Memorial day ceremony there, they honour the remaining internees: at the 2012 ceremony there had been eleven left, and at 2013’s, a couple of weeks after my visit, there would be only nine.

AT THE SENIORS' CENTRE in Unalaska, I had ingratiated myself by volunteering at the lunch counter. I’d served up cheeseburgers, chicken fajitas, frozen peas and corn. Later, I’d played board games with a handful of the residents. I had met Eva, another internment survivor, who had laughed and grinned when a staffer told her our shared name, but whose face had folded into a closemouthed frown when I told her I wanted to talk about the internment. I had met Harriet Hope there, too, and Sergie Krukoff, who ate lunch at the centre sometimes although he still lived on his own.

But I had also heard muttering and resentment out of earshot of the Aleut elders. They were “keeping the hate alive,” I overheard one white Unalaskan say. One elderly white resident of the centre, after hearing what I was there to write about, grumbled, “At least they weren’t fighting, like my two sons were.”

In fact, many of the Aleuts’ grown sons were fighting, even as their parents and siblings languished in government camps. It’s true that next to the horrors and fatal harvest of the entire Second World War, with its scorched continents and millions killed, the Aleut internment had been a tragedy on a tiny scale. But it had been a tragedy nonetheless. It was ironic that, here in this isolated place, a few people were tired of a debacle about which most of the world had yet to hear so much as a whisper.

I’d heard traces of anger from the survivors I’d spoken to—anger at the government that had mistreated them mixed with defiance and wounded pride. Mostly, though, I’d heard sadness. More than seven decades after they’d been taken from their islands, the longing they’d felt in the camps was still keen in each of them.

“I missed all the beaches, all the sea water, all the sea lions and the seals,” Sergie Krukoff told me on the afternoon I went to see him. He paused, staring out his kitchen window at the treeless hills covered in dry winter grass, the pacific Ocean stretching away forever. “The air is different in the Aleutians, too, than down there. You don’t get much air down there. In Southeast, you stay in the trees.”