Run for Your Lives!

Science-fictionist Robert Sawyer, the brainchild behind ABC's hit TV show Flashforward, can't wait for the future.

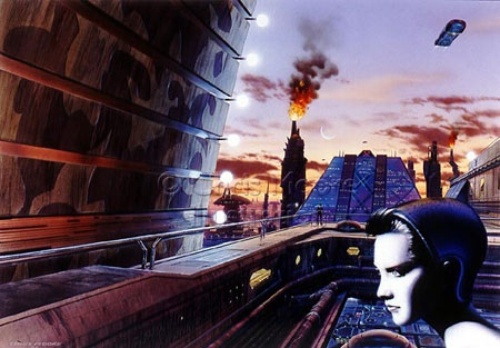

Computers that try to wipe out their human masters. Experiments that go horribly awry. Robots that run amok. Gleaming dystopias where individuality is outlawed. For a genre so preoccupied with technology and the future, it’s a little strange that science fiction’s default message has almost always been “Run for your lives!”

Canadian sci-fi author Robert J. Sawyer calls these “scare stories” and hopes that future-fear is a thing of the past. “Originally science fiction was about cautionary tales,” he says. “The problem was that it dissipated its moral authority in this area by decrying everything that was coming down the pike. And if you do that, if you’re always the guy who says, ‘Wait a minute, genetic engineering is going to be bad, AI is going to be bad, space travel, etc.,’ you’re the boy who cried wolf.” According to Sawyer, the only writer still crying wolf for a living is Michael Crichton (Jurassic Park, Andromeda Strain, Prey). “You pick the topic,” Sawyer says, “and things will go wrong, people will die. That’s Crichton’s message, that’s his mantra.”

As Sawyer sees it, the future is inevitable, so we better get used to it instead. Accordingly, Rollback, his seventeenth book, is more about adapting to the future than fleeing from it. In the novel, an elderly couple in Toronto in 2048 find themselves at the forefront of massive shifts in earthly reality. Don and his wife Sarah are each given a “rollback”—a procedure through which a person’s body gets reverse-aged by sixty years. There is lot of surgery and tinkering with DNA. An alien civilization has been communicating with Earth, and Sarah, the researcher who originally broke the alien code, needs to still be around when the next message arrives, somewhere around 2085. The procedure works for Don, but not for Sarah. So while he’s out flirting with co-eds, she sits at home and awaits the inevitable.

Sawyer’s previous novel, Mindscan, was also set forty years ahead in Toronto. In that one, a young man transfers his consciousness to an artificial body and lives to seriously regret his decision. Though Sawyer sees the two books as companions, he says it’s no surprise that Rollback is much less dark in tone. Being made much younger would simply be easier to get used to than being given a robot body. “There’s very little enthusiasm for the artificial-body perspective,” Sawyer admits. “Even from people who use walkers or who can’t chew their own food anymore.” Sawyer, for his part, can’t wait until rollbacks are a reality: “We still have all kind of problems—artistic problems, social-justice problems—that no one has been able to work out, because nobody has had a century to work on them.”

Though Sawyer firmly believes technology can be a force for good, he admits it can be abused. And not just by mad scientists or paranoid governments. He likens Margaret Atwood’s LongPen (the device with which a big-name author can meet readers and sign books half a world away without ever leaving home), for instance, to “the way people in biohazard labs deal with dangerous materials,” calling it “repulsive as a notion and demeaning to the audience” as well as “arrogant in the extreme.” Sawyer is very old-school about keeping in touch with his fans. “This idea that, as your stature grows, you owe less and less to your readership is totally wrong,” he says. “Your stature grew because of your readership.”

The other thing Sawyer believes in as a force for social good is pop culture. “As a creator of that stuff myself, I have a vested interest in believing it is not ephemeral, but will last.” His novels are littered with references to Star Trek and Seinfeld, and he admits to being something of an “evangelist” for the Pamela Anderson bookstore-set comedy Stacked. Citing All in the Family as evidence, Sawyer even goes so far as to half-jokingly suggest that “the sitcom was the principal American invention of the twentieth century and the principal engine for change in the last half of the century.”

In other words, dystopian visions are fine, but it’s hard to resist progress when it comes with a laugh track.

This piece originally appeared in issue 24 "Poolside Fiction" of Maisonneuve.