Pa’s Book List

An upcoming film based on Mordecai Richler’s Barney’s Version has stirred up new interest in the Montreal writer’s novels. His son tells us about the one book he never wrote.

My father made a point of not discussing his work with his children, so it was only natural that as I grew older I began to keep an eye out for whatever clues nevertheless came my way. Once, when I was living in London and he was on a visit there, I accompanied him to the second-hand theatre bookshops of London’s West End, on the lookout for books about tap dancing and vaudeville. I was keen merely to be with him, to learn a bit more about the London in which he had first made his mark, so I didn’t make much of our excursion at the time. His political travelogue This Year in Jerusalem had recently been published, and I had thought—no, truer to say that I had hoped—that out of that book’s pursuit of his childhood friends to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv would come a novel at least partly set in Israel. (How much I would still like to know what he would have made of al-Qaeda and the present Middle Eastern mess.) But as it turned out, the book that he was researching was the novel that started out as Barney Like the Player Piano, before my father took my mother’s suggestion and renamed it Barney’s Version.

I was no more astute about the next book, the one that didn’t happen—and that might have been ready by now—but there were signs. In October 2000, the year before he died, I stayed with my father in the Eastern Townships for Thanksgiving. Upstairs was where he worked, his table set before the windows overlooking the lake and the entire floor strewn with piles of newspaper clippings that he retained mostly for his National Post column. Apart from the fax, an instrument of mischief for him, my father disliked technology and his table was evidence of this. He wrote on a manual typewriter for most of his life and, when he did finally graduate to an electric one, there was nothing he could do to avoid spilling coffee, tea and cigarillo ash on it. He kept an indelible marker handy to rewrite the letters on the keys where his furious typing had worn out the decals. When, during his working day, my father did descend from his office, it was to fetch some more tea with lemon or to chat in low, confidential tones with my mother. On that particular weekend, I had my own column to write and was doing so at the dining room table when he passed behind my chair on his way to the kitchen. I was writing on an Apple laptop with which the National Post had supplied me.

“Where did you get that?” he asked. Covetously.

“The Post gave it to me,” I said.

“You mean they paid for it?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Why?”

“I need it for my work.”

“Oh, you do, do you?”

My father, amused, strode to the telephone and immediately called Ken Whyte, who was his friend and, as the Post’s editor-in-chief, his employer.

“I’d like a computer, Ken,” he said. “I need it for my work—and I want one that’s bigger and better than Noah’s.”

It seemed a fair bet that the new novel had computers in it.

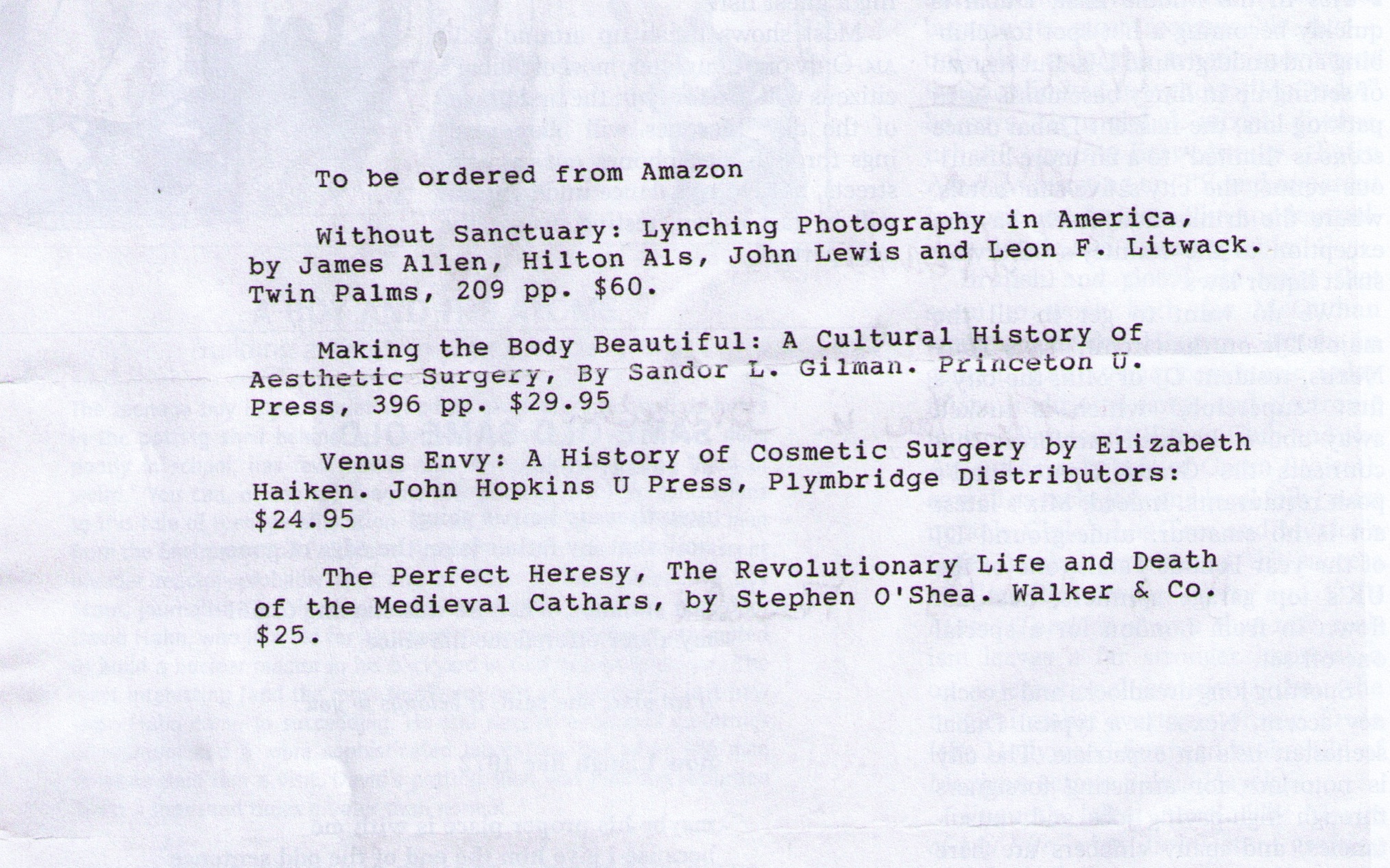

My father, a patriarchal figure, was especially pleased when his children ran errands for him, and a few months later he handed me the book list opposite “to be ordered from Amazon.” But he became ill soon afterwards, and I never did get around to doing his shopping for him, so the list has become a memento—a cherished one, a final and enticing clue that is no more than a fragment, really. In Vancouver a few months ago, I showed it to my friend, the novelist Michael Turner. He laughed tenderly and said, “But Noah, can’t you see? It’s a poem. It should be called ‘Errand.’”

Studying the terse list, I wonder what my father would have made of The Swan, the reality television show in which women publicly subject themselves to the plastic surgeon’s knife, or how he would have reacted to news that doctors are hard at work planning the transplant of an entire face. I know of a woman who got a nose job to match the decor in her new house and talked about the reasons for her “enhancement” openly. I wonder if he anticipated that teenagers would demand liposuction, nose jobs and breast enlargements (or reductions) as graduation gifts, and that the odd mom—one a New York writer, no less—would die for the sake of a nip and a tuck. What a subject plastic surgery would have made for him!

I consider the clippings I have kept myself: of Dolly the cloned sheep, and of the baseball legend Ted Williams, whose frozen corpse was the object of a legal battle between the .400 hitter’s squabbling children, one of whom—the son—saw money in it. I know how much my father would have liked that particular story, with its nearly Biblical aspect. Sure, he loved baseball, but as a writer I know that he relished even more the idea that children were freeloaders, connivers—ingrates out to squander the inheritance and probably carriers of herpes besides. Take another look at Barney’s Version, Joshua Then and Now, Solomon Gursky Was Here or The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz if you are in doubt. In his fiction, there are no easy times between fathers and sons.

So, a couple of books about plastic surgery, easy enough, but a history of the Cathars, and a book about the lynching of negroes in America? Just what kind of plot was the satirist in him embarking on? Transformation figured, certainly, but what else? I remember—I was a little boy then—a photograph he once showed me of grinning white Southerners standing beneath the charred corpse of a black man hanging from a tree. Young Jews, he instructed me, were at the vanguard of American blacks’ fight for civil rights. That mattered to him. And I recall a funny story he once told, of the novelist Edna O’Brien, who had undergone a facelift by then, approaching him and his American publisher, Robert Gottlieb, at a launch party in New York. “Edna,” said Gottlieb, “I remember you when you were our age!”

Walter Kirn, an American novelist whom my father once helped along, once complained in the New York Times that in these fast-changing times it is impossible for novelists to keep pace with events in the news. He was wrong.

(Originally published in Issue 11, October/November 2004, "The Underground Issue.")