Why Afghanistan is Canada's Next Korea

Pundits like to compare the current war in Afghanistan to America's involvement in Vietnam. But Canada's participation in the Korean war is a much more instructive precedent.

They’re at it again. Those American pundits whose memories stretch only about four decades back just can’t help themselves. They’re calling Afghanistan the next Vietnam.

Let’s evaluate the claim that has recently been made by some of the most venerable American media, including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Newsweek, among others. Like Vietnam, Afghanistan has been called un-winnable, despite massive infusions of troops. It’s a war of not just guns and roadside bombs, but also hearts and minds. Troops often can’t distinguish friend from foe, villager from insurgent. It’s asymmetrical guerrilla warfare. And opposition grows as combat losses climb higher.

Because of Canada’s long-term commitment to Afghanistan, the comparison has spilled north of the border. It seems we might be involved in our first Vietnam.

But let’s pause for a minute. Is this metaphor even useful for Canadians? We have 2,500 troops stationed in a very deadly part of Afghanistan, but that deployment pales in comparison to the hundreds of thousands of Americans—millions, taken as a wartime total—who served at the same time in Vietnam. Also, Canada has a volunteer military. Young men aren’t scrambling to stay in university for fear of falling victim to conscription.

No. There is another conflict lurking that, while comparatively different in several crucial respects, taught Canada a lot more about unwinnable wars than Vietnam.

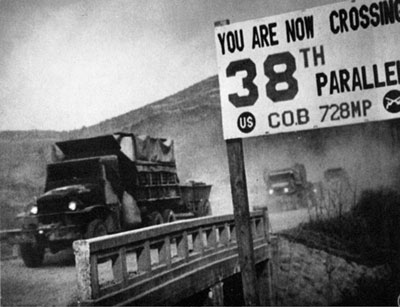

That war was fought on the Korean peninsula for three years during the 1950s. Indeed, Afghanistan isn’t Canada’s first Vietnam. It’s our second Korea.

United Nations troops withdraw from Pyongyang in 1950.

When Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent announced to the country on June 30, 1950 that he was considering a commitment of troops to the Korean peninsula, he said that “any participation by Canada in carrying out the foregoing resolution ... would not be participation in war against any state.” Indeed, the North Korean aggressors represented not their country, but an idea—communism—without any discernable home.

Eight years ago, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien told Canadians that we were part of a coalition of countries “that will act on a broad front” to snuff out terrorists. The primary Canadian theatre became Afghanistan, but not a single member of that coalition declared war on any other state. The totalitarian communism of the fifties and the terrorism of today might be apples and oranges, but they’re not exactly incomparable.

When he wrote an editorial that appeared in Maclean’s on Aug 1, 1950—just over a year after the Korean conflict erupted—Pierre Berton might as well have been describing the troubles Canada has had in Afghanistan for nearly a decade. Try a simple exercise while reading Berton’s words: replace “Korea” and “Korean” with “Afghanistan” and “Afghan”.

"The great lesson of the new decade is already clear: that the ends of military expediency are not enough, that you can’t burn away an idea with gasoline jelly but can only destroy it with a better idea. But this lesson hasn’t been put into practice.

[...]

"The other thing we must understand is that we all share some of the responsibility for what happened to the Korean people and their land. No matter who is to blame, it is we who must rebuild this wretched country, for victory will rest in the end with the side that gains the trust of the people.

"I believe this is the only practical aim we can follow in Korea if we are to come out of this business with our heads up and out ideals unsullied. The fact that it is also the moral course is perhaps an added argument in its favour. If we succeed with it we may yet make 'our way of life' seem worthwhile to the people who’ve had it inflicted on them for the past twelve months."

A few months later, the Maclean’s editorial board dampened Berton’s criticism of the war by encouraging all Canadians to stay the course in Asia – a message familiar to our troubling times.

"We’ve got a lot to do yet, all right. We could probably do it faster and better. But maybe we would do it faster and better if we threw away the crying towels for a while, stopped running each other down, and talked a little more about our solid and demonstrable accomplishments."

Of course, for all of the similarities—both among the punditry and on the ground—between Afghanistan and Korea, many differences remain. The terms of conflict were far different, as were the motivations to fight, the enemies, and the primary objectives.

Berton’s words are no less eerie, though. And as flawed as these historical comparisons may be, they remain instructive. Navigate over to Google and search for “forgotten war.” Take note of the first conflict that pops up. The Korean experience deserves better than to be largely ignored and replaced by false comparisons to a war in Vietnam that Canada never fought.