US Miltary Psychics

The incredible tale of how the CIA and American military spent $20 million trying to read people's minds.

Spies and psychics. They are as different as chocolate and peanut butter, and conspiracy theorists love them both. Throw them together, however, into the same story, and you've got a whole new level of fun and insanity—Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup on a millennial, almost Biblical scale.

So when word got out in 1995 that US military intelligence had been funding efforts to read people's minds for more than twenty years, the strange news inspired all sorts of excitement and derision—particularly when some of these same psychics expressed their belief in UFOs, time travel and alien-human hybrids.

One of the first military mentalists to disclose details of the program was David Morehouse. In his 1996 book Psychic Warrior, he recounts how, as a soldier, he started to have strange visions and out-of-body experiences after a stray bullet hit his helmet during a training exercise. Instead of getting psychiatric treatment, Morehouse, a decorated Ranger and airborne captain, was enrolled in the military’s highly secretive Stargate program.

Stargate had begun at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the early 1970s, in conjunction with a couple of laser scientists from the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), a body affiliated with Stanford University that did a lot of research for the U.S. government. One of the SRI scientists, Hal Puthoff, had already been dabbling in parapsychology when he was approached by CIA agents looking for a lab that could handle “a quiet, low-profile, classified investigation” outside normal academic lines.

According to Puthoff, the boys from Langley believed that the Russkies might be getting ahead in psychic experiments and felt that the CIA, too, needed to get involved—if only to figure out if the Soviets were capable of mind-controlling American generals.

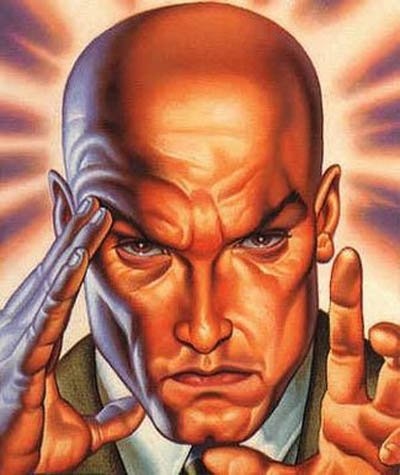

Puthoff, a high-level Scientologist, claimed that he could “remotely view” things that he couldn’t physically see—such as information on a building directory inside a locked building. The boys at Langley grew interested and, in 1972, the CIA started funding Puthoff and his “empaths” (often fellow Scientologists).

These were heady, psychedelic times. The previous year, a US Army intelligence official, quoting an astrologer, had warned that “there is great danger that within the next 10 years the Soviets will be able to steal our top secrets by using out-of-body spies.” Soviet efforts at mind-reading would later be largely discredited as hoaxes, but fears of a psychic cold war had a receptive audience in the fringes of the US national security establishment. Stargate possessed a veneer of science as well as the possibility of gaining formidable advantage over the enemy.

The military’s foray into crystal-ballism was also part of a broader attempt by US spies and solders to reinvent themselves in the dog days after Vietnam. Within the CIA, there had always been tension between factions accustomed to more hard-edged tactics (such as the Phoenix program, which tortured and assassinated suspected Vietnamese peasant leaders) and those staff who favoured softer techniques—such as dusting Fidel Castro’s shoes with poisonous thallium to make his beard fall off. Now, in the earlier 1970s, the kooky coalition seemed to gain the upper edge.

One of the gurus of this rethink was Jim Channon, an army lieutenant-colonel assigned to study ways of creating a more “spiritual” army. According to Jon Ronson in The Men Who Stare at Goats, Channon attended a retreat at the Esalen Institute for the Advancement of Human Potential in Big Sur. Led by mentor Michael Murphy, a founder of the New Age movement, Channon engaged there in Reichian rebirthing, primal arm wrestling (regular arm wrestling combined with guttural screaming) and naked hot-tub encounter sessions. When he emerged, Channon wrote a confidential report in 1979 that started: “The U.S. army doesn’t really have any serious alternative than to be wonderful.”

Channon’s report proposed the creation of a First Earth Battalion of Zen-master super soldiers with telepathic powers. These “warrior monks” would carry ginseng regulators in their uniforms, divining tools and a loudspeaker to play indigenous music and words. They would also give their enemies “an automatic hug” and carry lambs into hostile countries, a symbol of their peaceful intent. They would learn how to fast, sense plant auras, pass through walls and “stop using mindless clichés.” “It is America’s role to lead the world to paradise,” he wrote.

(Channon’s idea of using loud music to confuse the enemy was tested out a few years later on Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega. In 2003, in Iraq, US Army soldiers forced detainees to listen to children’s songs like “I Love You” from Barney and Friends. The technique continues to be used on al-Qaeda prisoners today—some of them, according to Ronson, locked blindfolded in burning hot metal shipping containers, forced into crouching positions and surrounded by barbed wire while the music plays loudly non-stop for days.)

Far from being ridiculed, Channon’s report deeply moved a group of senior army officers, some brought nearly to tears, writes Ronson, because they held so many pent-up emotions from Vietnam. Channon’s report also would serve as a vision for Stargate.

Mind-reading by psychics was, in a sense, a logical extension of earlier and more invasive mind-control experiments that had been going on since World War Two. The MKULTRA project, started in 1953, attempted to emulate mind-control techniques used on U.S. prisoners by the Soviets, Chinese and North Koreans during the Korean War. Under the MKULTRA aegis, pregnant women were blasted with radiation, US army soldiers were dosed with LSD to study panic, US Navy sailors were exposed to sub-aural frequency blasts to erase memory, and a group of Oregon prison inmates had their testicles irradiated—invariably without full knowledge or consent by the subjects. In all, more than 150 individually funded research sub-projects—most of which, due to deliberately destroyed records, we know nothing about—existed within MKULTRA and related CIA programs.

Soon after being founded, the Stargate remote viewing program was cancelled by the CIA and ended up in the hands of the US military. The transfer was prompted by the 1975 Watergate scandal and ensuing Congressional investigation of the CIA, which scuttled many of its more controversial programs (including MKULTRA).

Many at the CIA were happy to see Stargate go. According to The Wizards of Langley: Inside the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, one CIA man tells author Jeffrey Richelson that the official who had approved the program had been “out of his mind.” As a means of intelligence, he felt, Stargate was “useless” and “absolute bullshit.”

Indeed, those early experiments had led to mixed results for spying purposes, Richelson reports. The psychics had some accurate visions, but a very large percentage of what they envisioned was vague or plain wrong. In one operation, the early program’s leading psychic, Pat Price, was given coordinates of a Soviet military base in Kazakhstan, which Air Force intel thought could be a centre for particle-beam research. In four sessions spanning four days, Price gave what an evaluator judged to be “an almost perfect description of someone’s first look at the Operations Area” of the facility—low one-storey buildings partially dug into the ground, with a large crane. But other specifics given by Price—a 500-foot antenna, an outdoor pool, a nearby airstrip—were completely inaccurate.

Puthoff later touted the experiment as a success by pointing to the description of the large crane. But CIA officials didn’t agree, saying it amounted to lucky guessing. When Puthoff published some of his unclassified results in the journal Nature in 1974, an accompanying editorial comment called the paper “weak in design and presentation” and “disconcertingly vague” on details about the research methodology. A consistent problem was a lack of controls to ensure there had been no fraud.

The psychic research was a “dumb exercise” that produced “lots of laughing,” according to a senior CIA scientist quoted by Richelson, but it was justified because of the psychic research gap with the Soviets. When the Washington Post reported on CIA support for paranormal research in 1977, Richelson reports CIA director Stansfield Turner acknowledged the agency had had a man gifted with “visio-perception” of places he had never seen—a reference to Pat Price—but, Turner said with a smile, the man had died two years earlier, “and we haven’t heard from him since.”

Stargate’s new master, the US Air Force and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), quietly chipped in funds to keep the experiments going in the mid-1970s and eventually set up its own in-house psychic spying unit, funded by the US Army Intelligence and Security Command. Stargate’s headquarters was a run-down block of buildings at the Fort Meade Army base in Maryland.

By the 1980s, remote viewers had participated in dozens of intelligence-finding missions. Military sessions usually involved five to ten viewers with months of training all focusing on the same target in several sessions in order to make up for the limited accuracy of each viewer. The focus of viewing attempts included foreign buildings, Soviet submarines, Americans held hostage in Iran during the crisis of 1979-80, and in 1981, Brigadier General James Dozier, who had recently been kidnapped in Italy. The unit was praised by President Jimmy Carter for finding a downed Soviet bomber in Africa in 1979 after other spies had failed. Other missions of the psychic unit, according to a 1995 story in the Washington Post, include attempts to locate plutonium in North Korea and Muammar Gaddafi before the US raid on Libya in 1986.

Viewers also apparently tried their hand at some spacier stuff. One psychic took to trying to find the Loch Ness monster when there wasn’t any military work to do. (He determined that Nessie was actually a dinosaur’s ghost.) Another claimed to have killed a goat and his pet hamster by staring at them for days on end. And according to Ronson, a general in the program kept trying to walk through walls.

But members of the program tended to belie the stereotyped image of flaky New Agers. One psychic, Paul Smith, was a young US Army intelligence officer, Arab linguist and a devout Mormon. Analytical and clipped in both his writing and personal manner, Smith had no previous interest in extrasensory perception. As he writes in Reading the Enemy’s Mind: Inside Star Gate, America’s Psychic Espionage Program, Smith was recruited into Stargate in 1983 in part because of his skepticism about remote viewing. The program apparently didn’t want the true believers. Early research had also uncovered something surprising: “remote viewing” (a fancy military term for clairvoyance, or sending your “mind’s eye” to see things far away) wasn’t the exclusive domain of a few gifted psychics. Anybody could learn how to do it.

Although initially dubious, Smith says over the next seven years he became one of the army’s premier “remote viewers” and the main author of its extrasensory training manual. He would later serve as a tactical intelligence officer in the 101st Airborne Division in Operation Desert Storm/Shield. (David Morehouse, also a Mormon, entered the program in 1988 and trained under Smith.)

“My success rate was around 28 percent,” said one spy, Joe McMoneagle, to the Daily Mail newspaper this past January. “That may not sound very good, but we were brought in to deal with the hopeless cases. Our information was then cross-checked with any other available intelligence to build up an overall picture.” McMoneagle’s work eventually earned him the Legion of Merit, America’s highest military non-combat medal.

By one tally, of eighty-one projects between 1979 and 1982, twenty-one produced positive results, six were mixed, another six were terminated or not completed, and twelve were unsuccessful. The remaining thirty-eight received no evaluation or the results were not disclosed, according to Smith in Reading the Enemy’s Mind.

Even investigative journalist Jack Anderson, one of the first reporters to expose Stargate in a Washington Post column as a misuse of government funds, became a believer in the program’s value. “In concept if not always in execution, it was worth taxpayers’ dollars,” he wrote in the foreword to Smith’s book.

But many in the military remained skeptical. Fundamentalist Christians in the Army considered Stargate the Devil’s work. Nor was Stargate a well-supported program: lack of funds for renovations meant staff relied on scrap furniture to furbish much of their office. When one senator toured the program at Fort Meade, he apparently asked “where all the winos were” as he ascended the rickety steps.

In 1995, the program’s enemies finally won. In the throes of downsizing after the fall of the Iron Curtain, the DIA decided to kill Stargate. But remote viewing had a few friends in Congress, who pressed the CIA to take back the program it had started 20 years earlier. Urged on by supporters like Senator Claiborne Pell—sometimes referred to as “The Senator from Outer Space”—Congress mandated the CIA to review the usefulness of the 20-year psychic program, which had cost $20 million. The CIA, unhappy at the prospect of welcoming home the controversial mentalists, contracted out the study to the nonprofit American Institutes of Research (AIR), which in turn brought in two outside experts, statistician Jessica Utts and psychology professor Ray Hyman.

As a visiting scientist in the SRI program in the 1980s, Utts was a true believer in remote viewing, while Hyman was a longstanding debunker of all things paranormal, and a founding member of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. They had butted heads over remote viewing before and this study would ultimately only reinforce their positions.

Utts reviewed 26,000 remote viewing trials done in 154 experiments at SRI. Her conclusion: “The statistical results were so overwhelming that results that extreme or more so would occur only about once in every 10 to the 20th such instances if chance alone is the explanation… Obviously some explanation other than chance must be found.”

Utts also studied 445 other trials in six more recent remote viewing experiments overseen by an internationally reputed panel of scientists (including a Nobel winner for physics) at Science Applications International Corporation. She claims to have found statistically significant results supporting psychic phenomena in four of the six experiments and calls the evidence for remote viewing “a lot stronger than for many effects we accept in everyday life. It’s on par with the effect of aspirin in preventing heart attacks.”

Hyman was less charitable to Stargate than Utts. He admitted that the case for psychic functioning seemed better than ever, and conceded that the data was puzzling—“I do not have a ready explanation for these observed effects”—but remained unconvinced, primarily because “it is impossible in principle to say that any particular experiment or experimental series is completely free from possible flaws… especially [ones] that have not yet been discovered.”

English psychologist Richard Wiseman summed up the problem nicely in a recent article in the Daily Mail: “If I said that there is a red car outside my house, you would probably believe me. But if I said that a UFO had just landed, you’d probably want a lot more evidence. Because remote viewing is such an outlandish claim that will revolutionize the world, we need overwhelming evidence before we draw any conclusions. Right now we don’t have that evidence.”

Hyman also noted a practical issue: remote viewers were said to be accurate about 20 percent of the time, but this wasn’t good enough for intel purposes. “Without any way to tell which statements of the views are reliable and which are not, the use of this information may make matters worse rather than better.”

The final report submitted by AIR to the CIA was damning and recommended against pursuing the program. Remote viewing had “failed to produce the concrete, specific information valued in intelligence reporting,” it said. The CIA pulled the plug in 1995.

But far from dying a quiet death, remote viewing gained a new life. Shutting down Stargate meant that formerly employed military psychics could now go public with their knowledge of the program itself—at length and in best-selling books—and set up private practices to continue their experiments.

Paul Smith and David Morehouse have both started private remote viewing training businesses. Remote Viewing Instructional Services, Inc. in Austin, Texas, founded by Smith, offers a 50-hour Basic Remote Viewing Course ($2,000) that includes a lecture from Hal Puthoff, the guy who helped kick off the whole thing back in the seventies.

In San Diego and San Marcos (north of San Diego), David Morehouse Productions offers a series of classes, from two to five days in length ($495 to $1,290). Classes are co-taught by Morehouse’s wife, Patty, and fellow psychic Jason Appleby. Students include police officers, border guards and medical professionals interested in becoming more perceptive about people they deal with on the job. Practising their techniques “heightens your intuition almost immediately. Once you do it more, you start to notice it more in a waking state too, learning to trust your gut more,” Appleby said.

What about using remote viewing for evil—cheating at cards or figuring out a bank’s layout? Appleby says some students start off wanting to use it to make money, but quickly drop the notion because remote viewing has significant limitations and is hard work.

Besides, Appleby said, students are quickly awakened to a spiritual side of remote viewing. “There’s something really profound about looking at the paper record of a session, having proof that there is more than just the physical body. People spend their entire lives in different faiths looking for just a glimpse of something like that, and here it is. It’s really something extraordinary. I think it’s the most profound story of history.”

(Reprinted from Issue 28, Summer 2008)