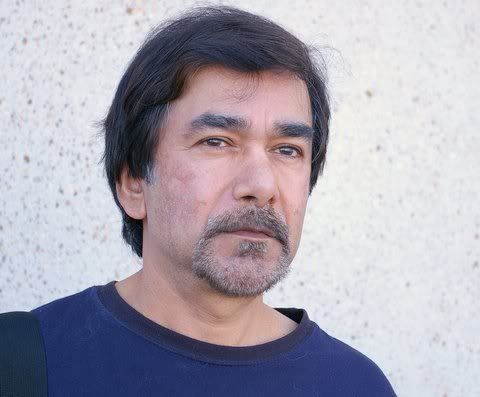

Interview With Rabindranath Maharaj

The Ontario novelist and short story writer discusses his childhood love of comic books and the inspiration for his new novel.

Novelist Rabindranath Maharaj was born in Trinidad, but immigrated to Canada in the 1990s after completing his second Masters degree – this one from the University of New Brunswick, in creative writing. His seven books of fiction -- including the highly acclaimed The Interloper (1995) Homer in Flight (1997), The Lagahoo’s Apprentice (2001), and A Perfect Pledge (2006)-- have been shortlisted for the Chapters/Books in Canada First Novel Award, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize.

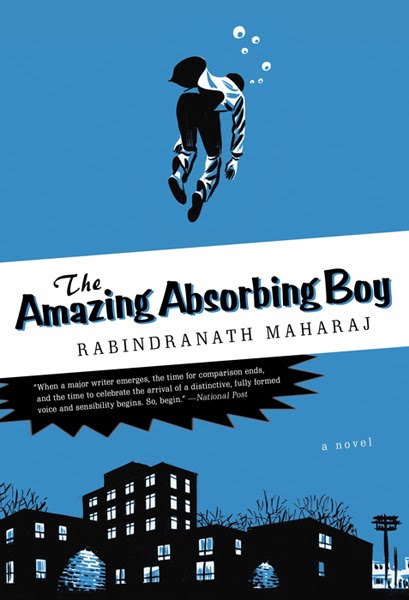

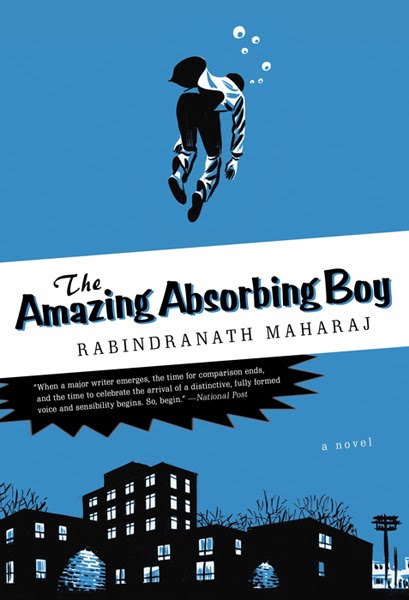

His new novel is The Amazing Absorbing Boy (Knopf Canada). It follows the adventures of 17-year-old Samuel, who leaves his village in Trinidad after his mother dies, and flies to Toronto to live with the father he’s never met. Rather than the parent with whom he’d dared to imagine reuniting, Samuel instead discovers a sullen, near-absent man, living in a place called Regent Park.

More about Rabindranath Maharaj and his books can be found at rmaharaj.wordpress.com.

Read an interview with Michael Cho, who designed the cover to The Amazing Absorbing Boy.

_______________________________________________________________________

Ingrid Ruthig: The epigram for The Amazing Absorbing Boy —“Gulp! It’s too late. He’s beginning to change”—mirrors comic-book style, but more importantly establishes the foundation and atmosphere for the story. This idea of transition strikes me as the novel’s key element, one that resonates on many levels. Given our current light-speed era, did you want to make a broader comment on the uncertainty, anxiety, and excitement that accompany big change?

Ingrid Ruthig: The epigram for The Amazing Absorbing Boy —“Gulp! It’s too late. He’s beginning to change”—mirrors comic-book style, but more importantly establishes the foundation and atmosphere for the story. This idea of transition strikes me as the novel’s key element, one that resonates on many levels. Given our current light-speed era, did you want to make a broader comment on the uncertainty, anxiety, and excitement that accompany big change?

Rabindranath Maharaj: My original title for the novel was The Age of Improvisation. My editor, Diane Martin, felt it was too dry and academic, and I agreed completely. The title alluded to the notion that this period would be defined by the complete refashioning of ourselves. I believe I was thinking then about the way technology was reshaping our interactions with each other, the ease of travel, the debates around religion and atheism, new notion of identities, etc. I felt that when historians and idlers looked back at our age, they would find it impossible to attach some meaningful label because everything had been so fleeting and transitory. Or maybe they would say it was the age of improvisation. Who knows? In the novel, I tried to keep most of this in the background. (Except for the chapter describing Danton Madrigal, a madman who fantasizes about sabotaging all these high-speed trains and computers, etc.)

IR: As a boy growing up in Trinidad, Samuel was an avid reader of comic books. In Toronto he uses his knowledge of them to buoy himself up, to see the familiar in the unfamiliar, and to view his new life as an adventure. Is he really as innocent as he seems though? If not, then why is he so often silent in the face of gossipy tales like those told by his gas station co-worker Paul, or the rantings of Danton Madrigal?

RM: He is really quite innocent. Or, at least, innocent and naive in the sense that he sees everything through the prism of his comic books. Certainly, some of this innocence falls away as the story progresses, but even then, he wants to believe the stories he’s been told by Paul and Dr. Bat and others. By immersing himself in the fantastic world of these characters, he is immunizing himself from his other life, the "real" one at Regent Park with his hostile father. In Chapter Five, he says, “One rainy night as I was walking home… I felt that all their (Paul’s and Dr. Bat’s) strange stories had pushed away my worries about my father’s mean behaviour. For a few hours every day I was immune.” IR: They also seem to insulate him from painful memories of his mother. Was documenting ‘the immigrant experience’ from a different angle one of your aims? Or did you want to reach even further, and examine the ways in which people find themselves ‘orphaned’ and how they cope with that? In other words, was the story a means of achieving a wider, fresher look at who we all are, and how we absorb and adapt to our surroundings?

IR: They also seem to insulate him from painful memories of his mother. Was documenting ‘the immigrant experience’ from a different angle one of your aims? Or did you want to reach even further, and examine the ways in which people find themselves ‘orphaned’ and how they cope with that? In other words, was the story a means of achieving a wider, fresher look at who we all are, and how we absorb and adapt to our surroundings?

RM: I know reviewers and many readers focus on the immigrant experience in novels like these. Fair enough. However, when I began the novel I also had in mind the type of story I enjoyed as a boy, one in which a young person, thrust into a strange place, tries to apprehend the unfamiliarity by coming up with magical interpretations and references. I felt it was entirely possible that a young foreigner might try to understand a big city in this manner.

IR: Samuel’s father, who sends for him yet doesn’t welcome him, remains a mystery. He’s been in the city awhile, and it’s clear that he’s a miserable man. However we are only able to sketch an idea of the rest. Why did you leave him like this?

RM: I would like to say that the father’s enigmatic character began when I was a high school teacher in Pickering. There, I would encounter students with some Caribbean connection. When asked about their fathers, many of these students were vague, ashamed, and even hostile. It took a while before I realized that their fathers were mostly absent figures in their lives. However, the more deliberate reason for setting Samuel’s father this way was because of my memories of the more fascinating comic-book villains. There was always a sense of mystery about the realistic villains, and their diabolical dealings were sometimes offset by moments of unexpected (and jokey) generosity. Toward the end of the book, Samuel says of his father, “He was like the Spectre or the Shadow or one of these comic-book characters who had no friends or family and slipped in and out of dimensions to change into either hero or villain according to the crisis they faced.” He had to remain in the shadow, an elusive figure that Samuel could also “recreate.” A part of Samuel’s fantasy world was pretending his father had some secret identity.

IR: Samuel’s father seems to have failed on all levels. Was his ultimate failure his inability to change?

RM: Yes, definitely. In referring to the father, Uncle Boysie says, “A dreamer with no dreams is just a madman.” Not to get too Oprah-ish, but in a sense this novel is about the power of the imagination. Samuel was able to construct this magical city and to transform his experiences into adventures; his father, lacking this perspective, saw only obstacles in his path.

IR: The coffee-shop fellows with whom Samuel becomes friendly are particularly interesting, because they give voice to those who have been in this country awhile, or were born here and have nowhere else to call “home.” How did you see them?

RM: For the purposes of this novel, I saw them through the eyes of Samuel. He was fascinated by the way they looked down on recent immigrants and on teenagers, and their anxiety about any kind of change. However, he concludes that they are no different from old folks elsewhere, and he actually compares them to the old fishermen in a pub somewhere in Mayaro, sipping rum and talking about “the good old days.”

RM: For the purposes of this novel, I saw them through the eyes of Samuel. He was fascinated by the way they looked down on recent immigrants and on teenagers, and their anxiety about any kind of change. However, he concludes that they are no different from old folks elsewhere, and he actually compares them to the old fishermen in a pub somewhere in Mayaro, sipping rum and talking about “the good old days.”

IR: It’s natural and understandable for a person from elsewhere to want to connect in their new home with what’s familiar, if there is anything. But in doing so, have they made it difficult for themselves to move forward?

RM: It really depends on the extent of this connection. If nostalgia creates an idealized and false representation of their old homes, then it’s probably counterproductive. But if they are able to make connections and minimize their anxiety about being perpetual outsiders, it can be beneficial both to themselves and to their new homelands. No one, in my view, would want to completely cast off the forces that shaped him or her.

IR: The episodic nature of the novel stems from Samuel’s various attempts to fit in, earn money, and go to school, as well as from the fleeting comings and goings of people in his life. “I never saw him again” is a recurring line, and not just with Samuel. Is this a way of illustrating how any life is built on a collection of these seemingly unimportant meetings and disappearances?

RM: Especially for a young boy in a big city. When I was the Writer in Residence at the Toronto Reference Library in 2006, I noticed there were all these groups walking about in Toronto. They all seemed disconnected from each other. I wanted to give a sense of this in the novel. But there was another reason, and once more, I will return to the type of story I once enjoyed. There, the heroes were wanderers who encountered a host of characters they would never meet again. Each taught the hero something about his (they were usually male) journey, his life, his destination, and his purpose. Some of these books had a fable-like quality; once I decided on the comic-book angle to The Amazing Absorbing Boy, I realized it would work well here.

IR: Despite his Uncle Boysie’s instruction to prepare a description of “a regular Canadian”, Samuel can’t figure out what to tell him, except that it “was someone who fussed all the time.” From one standpoint, Samuel might already seem pretty “Cyanadian”—he’s quiet, polite, rule-abiding. When his uncle wants to visit a strip club with him, Samuel says he can’t go in because he’s not old enough. What is it about Samuel that has helped him to change this much already?

RM: Because of the special circumstances of his early life in Mayaro—fatherless, an only child, with a sick mother, etc.—Samuel was always polite and rule-abiding. In Chapter One, he mentioned that his friends called him a “housey-bird” because he remained at home to help his mother. Later in the novel, he mentions that his relatively solitary life in Mayaro had prepared him for Canada. In any case, I am not sure that “quiet, polite, and rule-abiding” would apply to all Canadians. Maybe people of a particular generation, like the old-timers in the coffee shop.

IR: Your writing often reveals a mischievous streak. To Samuel, people resemble Christopher Plummer or Lee Van Cleef, and do comical things, as with the old “teeth-doctor” Mothski, who pries open Samuel’s mouth to inspect his teeth. Many character names are deliciously Dickensian with a twist of modern comic book—my favourites are Mr. Bunglevalley, Dr. Bat, and Captain Hindustani. Do you find particular pleasure in inventing names and mannerisms? In what way do they themselves serve the story?

RM: Samuel’s nicknaming of these characters is a way of recreating the city, of refashioning the characters, of negotiating his journey through his terms. There is an air of unreality about these characters, which suits Samuel’s purpose and my own narrative intention.

In a broader sense, my inclination towards these eccentric characters is associated, I believe, with growing up in Trinidad. There, everyone has a nickname, and these nicknames are frank, telling, cruel, and funny. Maybe for this reason I enjoyed this tendency in books by Dickens.

IR: Do you think that there is an audience for books like The Amazing Absorbing Boy in Canada?

RM: I really don’t know. It’s likely that particular types of books possess a built-in constituency: people who read these books because there’s some type of cultural affinity with the subject matter, or they can identify with the writer in some manner, and so on. While the reviews for the book have been generally very favourable, one or two expressed a bit of tiredness, as in, “Oh no! Not another immigrant novel.” I cannot say whether this is representative of some portion of the wider society. I hope it’s not.

RM: I really don’t know. It’s likely that particular types of books possess a built-in constituency: people who read these books because there’s some type of cultural affinity with the subject matter, or they can identify with the writer in some manner, and so on. While the reviews for the book have been generally very favourable, one or two expressed a bit of tiredness, as in, “Oh no! Not another immigrant novel.” I cannot say whether this is representative of some portion of the wider society. I hope it’s not.

IR: That said, over the course of seven books, you have traversed the territory of the immigrant’s past and present. What have you absorbed that you haven’t written about yet? Figuratively speaking, where would you like to travel with your next book?

RM: It’s hard to say. I never plan out these things. I begin a book in an instinctive manner, and I allow the themes to define themselves in the first couple of chapters. Once I realize where the book is heading, I may go back to the beginning and modify portions, or rewrite everything. I have an idea for a story that revolves around an interview conducted by an earnest journalist. His subject is a religious nut. I suppose this book may be about the manner in which we are defined by the media, and the intersection of public and private lives. We will see.

Ingrid Ruthig is a writer, editor, and visual artist living in Ajax. For more information visit ingridruthig.wordpress.com.