Montreal: The Olympic Legacy

Back in 2003, when Vancouver was putting together its bid for the 2010 Winter Games, Dick Pound -- a member of the International Olympic Committee -- defended the legacy of the 1976 Montreal Summer Olympics in Maisonneuve.

The Olympic Games are the stuff of both legend and fact. The legend that surrounds Canadian hosting of the Games, especially those in Montreal, is that they were ruinously expensive and a drain on the resources of the community and the country as a whole. Twenty-seven years after Montreal was the host city for the 1976 Olympics, the legends need to be exploded and fact substituted for fiction and media exaggeration.

The idea to host the Games in Montreal was the brainchild and dream of the visionary mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, who believed Montreal was a city that deserved to be on the world, not just the national, stage. It was he who attracted the first major World Exposition, Expo '67, to Montreal as the showcase event of Canada's centennial celebration. The year before Expo '67, he launched a bid for the 1972 Olympics, only to be beaten by Munich, as the International Olympic Committee was unwilling to hold two successive Games in North America. Undaunted, Drapeau persisted for 1976, beating out two other cities, Hamilton and Toronto, as the Canadian choice. In a brilliant campaign, he triumphed, to the surprise of the world, over two better-known cities from the superpowers of the day, Moscow and Los Angeles. Moscow was trying to open the Soviet Union to the world and Los Angeles hoped to celebrate the two hundredth anniversary of the US Declaration of Independence. Adroit campaigning allowed Drapeau to sneak up through the middle of the Cold War powers to win the prize. The superpowers had to wait their respective turns, with Moscow in 1980 and Los Angeles four years later.

Translating the dream into reality proved to be more than Drapeau had anticipated. The rest of Canada thought that Montreal had had its day in the sun with Expo '67, one of the most successful world fairs in history. No federal funding was to be provided for the Games. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the federal government of the day, a Quebec-based minority Liberal government, was wary of showing favouritism. Even access to normal government programs was difficult. The idea of separate Olympic funding was unthinkable. Between the awarding of the Games in 1970 and 1973, a stalemate occurred. Even the idea of accessing non-tax base revenues through a special Olympic lottery, which required federal legislation, was stonewalled. Adding to these problems was a worldwide inflation trend, which caused every single major infrastructure project, including the James Bay hydroelectric construction, to run way over budget. The federal dithering reduced the time available for the Olympic project from six years to three.

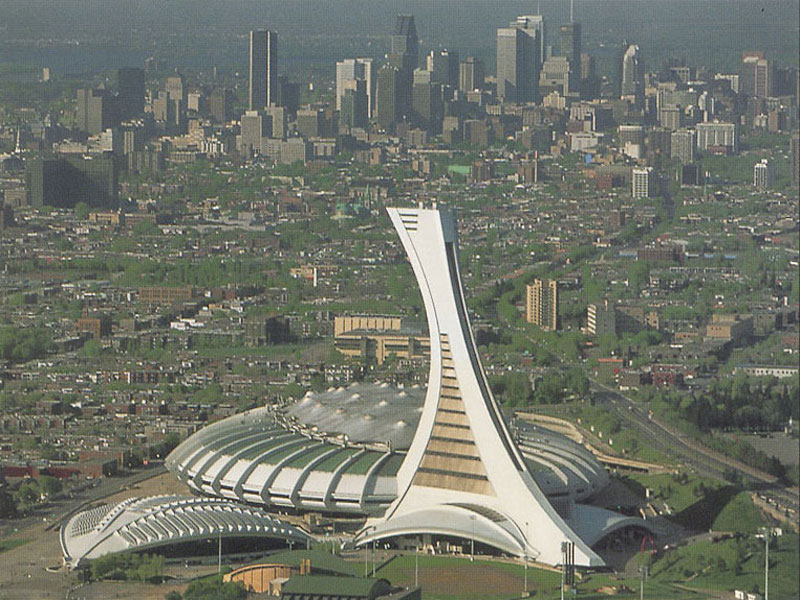

Montreal, under Drapeau's iron control, made its own mistakes. It had not made Olympic peace with its labour unions. Drapeau, in search of lasting monuments to make Montreal a world capital, chose a stadium design that was artistically magnificent, but unsuited to anything but major track-and-field, or possibly football, competitions. The elliptical design was expensive and the covering roof was not well suited to the climatic conditions of Montreal. When combined with the enormous inflation, these factors would make the Olympic stadium by far the most expensive in North America. Nor, to be fair, was the Olympic project particularly well managed by the city of Montreal, so much so that the Quebec government was finally obliged to intervene and take it over, to ensure that the facilities were completed in time for the Games.

From a public perspective, however, the most serious error made by Drapeau was to not separate the Olympic-specific costs from the basic infrastructure improvements, such as roads and the extension of the superb metro system, that Montreal needed with or without the Olympics. The result was that the public, spurred on by the media, who appeared to wilfully misunderstand the difference between the Olympic construction and the long-term infrastructure investment, was led to the belief that all such costs were Olympic costs. To this day, a significant number of Montrealers still believe that the Olympics "cost" $1.3 billion, even though the vast majority of the infrastructure is still in use more than a quarter-century later.

The fact, not the myth, of the matter is that Drapeau, often castigated for his statement that the Montreal Olympics could no more incur a deficit than a man could have a baby, was right. The Olympic lottery sanctioned by the federal government had a singular feature that made it a cash cow that could easily have paid not only for the real Olympic costs, but also for all the infrastructure. Its prize was $1 million. The tickets cost $10 and it was by far the most successful lottery in Canadian history. Had it continued for a few years, its proceeds would have covered all of the investment in infrastructure. But the federal government changed with the election of the Progressive Conservatives under Joe Clark and, in 1979, the federal government turned all the lotteries over to the provinces. The cash cow dried up. Montreal was left dangling.

The Games themselves had made an operating profit far in excess, on a per capita basis, of the celebrated Los Angeles profit eight years later. This profit was used to pay for several of the Olympic installations. The balance of the infra- structure was financed by borrowings. Financing of this nature is a technique regularly used by governments of all levels, as well as businesses and, indeed, individuals. When I bought my first house, I did not have enough money to pay the purchase price, so I borrowed money for the purpose, using the security of the property to acquire a mortgage. Of course, I incurred an interest expense, but, in the meantime, I lived in the house. Montreal borrowed money for its infrastructure, but had the use of it in the meantime as well. These were not Olympic "costs," but investments in the future of a growing and exciting city. These investments would eventually have been made. The Olympics brought the advantages to us sooner.

Montreal staged magnificent Games, saving the institution from the terror that had afflicted Munich only four years earlier. We should be proud of our city, of its role in Olympic history and of the vision of a mayor who believed, rightly, that we should play on the world stage.

Since 1976, the economics of the Olympic Games have changed dramatically and the possible drains on host cities are almost non-existent. Some examples: the worldwide fees for television rights for the Montreal Games were $35 million. By the time of Atlanta, only twenty years later, they had reached $935 million and for Beijing in 2008, they will approach almost $2 billion. Sponsorship revenues have grown from a net of $8 million in 1976 to almost $1 billion. The Winter Games revenues are not far off those figures, even as a smaller event with only seven sports compared to the twenty-eight for the Summer Games. These revenues can even be used to help offset the infrastructure investment in facilities. If today's host cities cannot fund all aspects of the operating costs from outside revenues, television, sponsorship, licensing and ticket sales, well, they are just not doing it right.

Vancouver's bid for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games will be voted on in early July. It is a superb bid and will provide a unique injection of funds and community involvement that can do wonders for the city and for a province that is struggling economically. During the recession of the mid-1980s, the Olympic projects in Calgary were almost the only new activity in the region and Calgary made a surplus of well over $100 million and has been left with a wonderful legacy of training and competition facilities that would never have existed without the Games. The Games put Calgary and Western Canadian hospitality on the world map in much the same way that the 1976 Games did for Montreal. Vancouver, and Canada, should seize the opportunity with all the enthusiasm it can muster. The prize is well worth the struggle.

Despite the many issues that always surround the Games, such as cost, politics, size and the use of performance-enhancing substances, the Olympics remain the foremost sports event in the world and continue to inspire young athletes and the world public. Everyone, everywhere, wants each Games to be a success. In some ways, they are a microcosm of the world: if the Games can work, then maybe, just maybe, so can the world at large. For athletes, today as in the past, the thought is irresistible that someday they may represent their country at the Olympic Games and (if everything goes perfectly) become an Olympic champion. There is no experience in the world that can compare with marching into the Olympic Stadium at the opening ceremony as part of your country's Olympic team, surrounded by the finest athletes in the world. Just to have been good enough to get there is an intoxicating life experience that has no equal.

(From Issue 3, Spring 2003)