Alex Chilton (1950-2010)

A look back at the rock star, cult figure and king of slovenly cool.

ROCK STAR and ne’er-do-well Alex Chilton, who died on March 17th, 2010 of a suspected heart attack, gave good non-interviews, which is to say he knew how to wriggle free of a line of questioning like almost no one outside of elected office. “[F]or you to write about me would be the best way for me to begin to have something against you,” he told Mojo on one occasion. “I have to rest my voice,” he told Rolling Stone on another (after a show, as he brandished, of all things, a cigarette, which might’ve been meant to double as a makeshift middle-finger).

In these, our Heisenbergian times -- when the sheer observation of an event, it’s accepted, can’t help but change the event -- a thwarted journalist will know enough to make her failure to land a story a part of the story itself. Gay Talese’s account of a near-meeting with an ailing Frank Sinatra is one such early classic of this sort of amateur astronomy, in which the close call with the shooting star is regarded as better than nothing and duly logged. Encounters with the Memphis-born Chilton (including those in which he actually answers questions) are probably better described as close calls.

Perhaps Chilton, who could lay claim to the authorship of some five or six legitimate pop standards, sensed that he should safeguard his legacy by not exhausting their meanings in conversation with tape recorders. Or perhaps he had little to say about these standards, which it was perfectly in his rights to feel weren’t worth getting worked up about. Or perhaps he had an advanced understanding of the showman’s injunction to always leave an audience wanting more: give them nothing much in the first place. Some of Chilton’s live performances -- in their withholding of just about anything a paying customer might actually want to hear -- could resemble a kind of performance art. And Chilton himself could resemble a kind of performance artist, hermetically sealed-off from his patrons who must be content with their mumbled asides to one another because the artist, preoccupied with his fretwork and other noodlings, has turned away -- turned inward – as if protesting an abstract, unspecified injustice. (Chilton has been compared to Melville’s legal-copyist Bartleby, a performance artist in his own right. Bartleby, students of American lit will recall, refuses to work -- “I would prefer not to”, he calmly repeats – and, like some avant-garde exhibit, stands stock-still in the middle of his workplace.)

Chilton could resemble such an artist and still draw the crowd he drew because of the two or three pivotal contributions he’d once managed: the production of early tracks for the Cramps; the cutting of the aforementioned five or six standards, including especially “Bangkok” (1978), a postcard’s worth of travel writing (or an excuse for a lascivious pun) set to two-plus minutes of scrappy music, with Chilton on guitar and, double-tracked, some other Chilton working the drum-kit; and, finally, the recording of Chilton’s own solo long-player, Like Flies on Sherbert (1980), which an astute minority (with flawless taste, I might add) rates among the very best of our rock and roll.

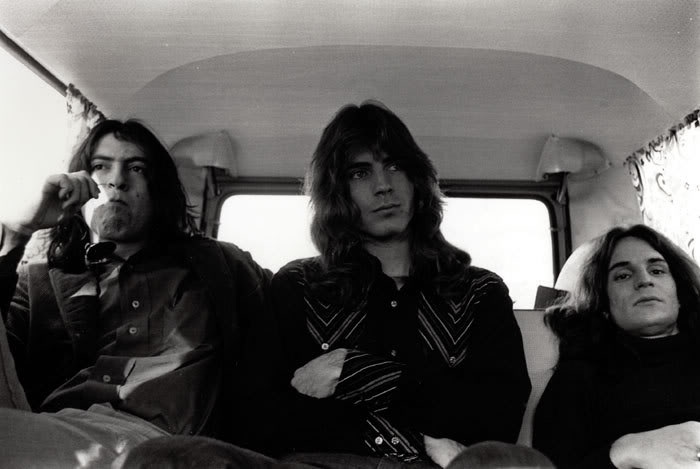

Chilton was born in Memphis and, as a teenager, enjoyed an early success -- his whole fifteen minutes of allotted fame -- with a boy band of the 1960s called the Box Tops. (Even then, Chilton appeared to be drawn to the lascivious pun.) He drifted in and out of bands, a songwriting partnership, eventually making his way to New York, where he got “Bangkok” onto tape. (The B-side, a cover of an old chestnut by the Seeds, was every bit the A-side’s equal.) He was the authentic punk: a punk by necessity. As one critic clarified, “The fact that pictures of him in New York from this period make him look like Richard Hell was simply down to the fact that he couldn’t afford to buy clothes or shoes.”

In 1980, he released -- I want to say "unleashed" -- Like Flies on Sherbert. Nobody bought the thing at the time, and by that I mean that transhistorical and well-placed Nobody who was present to purchase the first album by the Velvet Underground, the first edition of Howl, the first issue of transition, etc. Sherbert certainly didn’t sound promising, at least for the opening few bars of lead-off track “Boogie Shoes,” on which Chilton’s band sounds hard-pressed to rouse itself and Chilton, whom someone has foolishly entrusted with the vocals, comes in prematurely on the wrong beat. The false start is left in but then it doesn’t matter; the track has won you over, if not made you aware of, that perverse part of yourself which enjoys a pile up (and, anyway, you find you rather prefer the redundancy; later, same song, Chilton will hold the plosive ‘p’ of the lyric “I want to do it til I can’t get it up” a farty microsecond too long, like a saxophonist exceeding his instrument’s natural limits).

Sherbert -- like Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), that era’s other great work of detumescence -- is all about exhaustion: rockets at the ends of their arcs; fuselage at its most flaccid; big stars imploding. Songs are started and scrapped abruptly; Chilton isn’t always near the required mic; guitars are slashed at arbitrarily; and primitive electronics are prone to gurgle, die. (It’s a record in the passive voice.) The music, a blend of covers and originals (the covers befouled by sheer proximity) fairly lurches through its genres: refried R&B, breakneck rockabilly, torched country, punk schlock, and girlgroup bubblegum -- all in the Lynchian mode (which had yet to be worked out, formally).

Producer and pianist Jim Dickinson, of the Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses”, presided over the sessions, some of which were held in no less a Memphis landmark than the Sam C. Phillips International Studio –- although it’s hard to think of sessions which sound less reverential toward the supposedly hollowed ground they inhabit; the Studio might as well be some asshole’s garage for all the love it’s accorded. In surviving B&W footage of the sessions, a hooded man (a figure out of snuff films) beats the strings of a double bass with a drum stick. Chilton’s eyeballs can be observed to bulge as he affects a comic, Transylvanian accent. Others caper about, into range of the camera, Bacchanalian-like. It’s the footage that’s shot by those carefree types who still feel safe in their excesses; the footage that’s later found by the authorities in horror movies.

To the chagrin of his fans -- a long-suffering lot -- Chilton didn’t pursue the Sherbert sound too much further; in the 1980s and 90s, he reinvented himself as a washer of dishes (if legend has it right) and interpreter of standards (the kind not written by Chilton himself). But if he seemed to be phoning in his live performances, then he was also communicating, as Andy Warhol did, from a calculated distance (Warhol, you might recall, loved the phone). And if Chilton, the interpreter, seemed to be defacing the Great American Songbook, then he could also be said to be annotating it, scribbling in its margins. (His take on something called “The Oogum Boogum Song,” from the 1999 covers album Loose Shoes and Tight Pussy, restores a dusty classic to its rightful gleam.) Like Peter Buck (guitarist for REM and, more significantly, professional music nerd) and the Cramps (who’ve done their share of restoration themselves), Chilton is an archivist of the already-decided-against: dusty classics, yes, but also the songs Oedipa Maas, from another Pynchon novel, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), finds herself listening to: “songs in the lower stretches of the Top 200, that would never become popular, whose melodies and lyrics would perish as if they had never been sung.” Chilton taught a generation of hipsters how to acquire their acquired tastes; and if they couldn’t always make sense of his -- he had a penchant for such stuff as “Volare” -- then they missed what might have been a point of his career: taste makes no sense (or cents; Chilton’s investment in the meanderings of his taste was not a lucrative one).

In his later years, and among his more nonsensical career moves, he unearthed a cache of obscure songs which he co-wrote in the early ‘70s with someone named Chris Bell. (Chilton and Bell briefly co-helmed a band or something.) Chilton began to perform these songs again and even cut a new album with an improvised line-up, including surviving members of the original arrangement and some choice ringers. Fans of Sherbert couldn’t appreciate Chilton’s renewed interest in these obviously minor songs, dashed off in his twenties, if not adolescence. But then Chilton often seemed to have a perverse understanding of his own historical importance. (Indeed, he’d have us remember the minor works at the expense of his actual achievements.) Funnily enough, Fox’s sitcom-cum-Bildungsroman That ‘70s Show employed one of these minor songs, “In the Street,” over its opening credits. The song must’ve struck the creative minds behind the show as sufficiently naïve, but at least they had taste enough not to use the original version of “In the Street”, commissioning instead a superior cover by Cheap Trick.

Critics who must come up with something to write about a cult figure like Chilton will list the far more successful artists on whom the cult figure (against good sense, all odds, the marketplace) left a clear impression. Chilton, we’re informed over and over, inspired the likes of Buck as well as the Replacements, Teenage Fanclub, the Bangles, This Mortal Coil, Jeff Buckley, etc. His is a respectable list of protégés, but it’s smaller than some want to admit and always about the same in composition, give or take. (No one who values her time would bother to undertake a list of those entities influenced by, say, a Bob Dylan; like the sun’s, Dylan’s influence over whole hemispheres of peoples is merely assumed.) Chilton, too, is often credited with patenting an energy drink called ‘powerpop,’ from which others made the fortune which Chilton should’ve.

Chilton’s real and lasting influence has been on the aforementioned hipster. Chilton’s music is the sort of fetish item the “flawless taste” is expected to cite. It’s part of the curriculum, and to have come to an understanding as to why one should opt for an Alex Chilton over, e.g., a James Taylor is to have achieved the hipster’s equivalent of the Bachelor of Arts: the bare minimum required to make one’s way in the rarefied world of the record store and the soon-to-be-gentrified neighbourhood. Hipsters owe him not a little for their sense of slovenly cool and ought to pay his estate the appropriate royalties. They might start by buying another copy of Sherbert, this one for an unenlightened loved one. Or, even better, they might buy one of the rarely bought late albums. Of course, we don’t owe it to Chilton to blindly remember the music which he would like remembered. Indeed, in the long run, it’s probably best we remember the music that matters to us -- the “Bangkoks” and Sherberts -- in the interest of other sides of stories.

Jason Guriel is author, most recently, of Pure Product, a poetry collection, and the recipient of the 2009 Editors Prize for Reviewing from Poetry. His work is forthcoming in Poetry and Parnassus. He lives in Toronto.