Negotiating Negative Peace: The Good Cause at the CCA

A Montreal museum's latest show highlights the importance of building in war-torn areas.

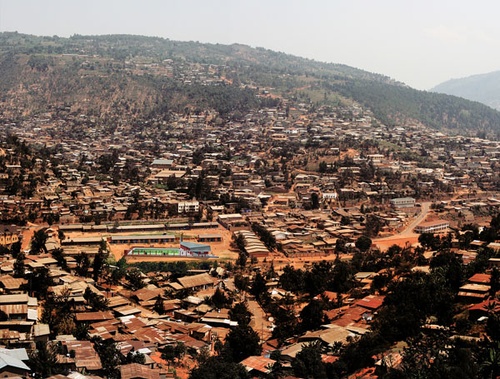

View of Kimisagara and the proposed football sports centre, Kigali, Rwanda—one of six projects documented in the CCA's The Good Cause. (Concept: Architecture for Humanity / Killian Doherty.)

War, unlike peace, does not need keeping. It sprawls, it fills, it strips, it razes. Even after the fighting forces have made their exit, it can still take years—even decades—for a war-ravaged region to regain stability. The fact that the post-war void, or so-called "negative peace," can be as corrosive as war itself is a central focus of The Good Cause: Architecture of Peace, the newest exhibit at Montreal's Canadian Centre for Architecture.

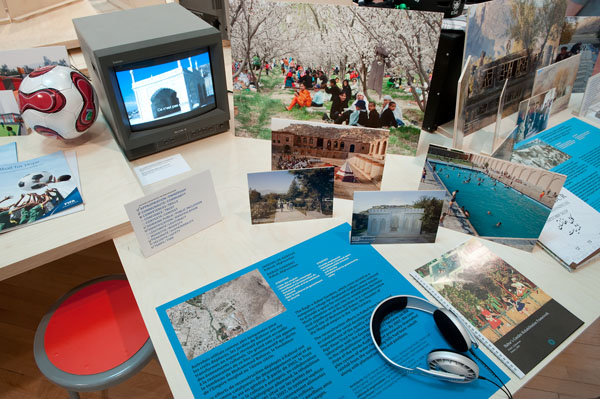

The Good Cause acts as a sort of peaceable counterpoint to the CCA's primary exhibit, Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War. While the latter spans several spacious, interconnecting rooms, containing enough artifacts and reading material to occupy the conscientious museum-goer for a full afternoon, The Good Cause is contained in a single, octagonal room smaller than an average high school classroom. Don't let its smaller stature fool you, though: the show, which is presented by the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam, is light on physical artifacts but heavy on ideas.

Architecture in Uniform sheds light on the roles of civilians and industry in war—specifically the most brutal and deadly conflict the world has ever known, World War II. The Good Cause broadens that discussion and lays bare the facts of war and peace, using giant maps that chart both wars and peacekeeping missions since the 1940s. (Unsurprisingly, the number of wars dwarfs the number of UN- and NATO-led interventions.) When collected, the estimated casualties for each conflict—8,000 here, 20,000 there, and those are just the small skirmishes—are staggering to consider.

An installation view of The Good Cause at the CCA.

The Good Cause focuses on architectural projects used to combat negative peace, the in-between time when the area used as a battlefield remains militarized and the destruction visited on the landscape has yet to be fixed. This exhibit demonstrates how both the physical barriers constructed to protect peacekeepers and constant ongoing tension can negatively affect a population's collective psyche, especially that of its youth. The Good Cause celebrates projects which were initiated to ease tensions and give locals space in which they could rebuild their sense of community—a skate park in Kabul, a soccer pitch in Kigali, Rwanda—using a combination of video, photographs, artifacts and reading material. The six projects exhibited here are also graded according to a list of criteria with regard to their effectiveness: to what degree they involve the populace, for example, or whether they reflect local culture.

For those of us living in North America—a segment of the exhibit's maps conspicuously free of wars or peacekeeping interventions, from the twentieth century onward—it can be easy to overlook the complexities of maintaining peace and restoring a sense of wholeness to a place ravaged by combat. The Good Cause acts as a reminder that, in war-torn areas, architecture and urban planning are more than something simply to be walked upon or driven through; they can be powerful forces for positive change.

The Good Cause: Architecture of Peace is on display at the Canadian Centre for Architecture until September 4.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Exploring Outer Space Through Architecture

—Journeys at the CCA: The Architecture of Migration

—The Architecture of War at the CCA

Subscribe — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook