RiPod

Apple co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs has died at fifty-six.

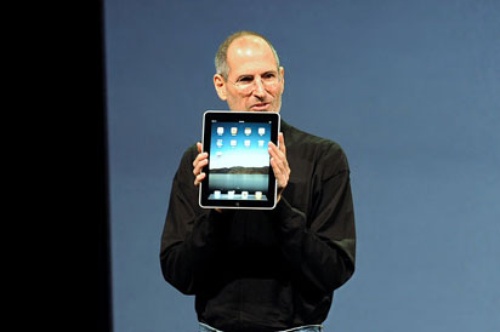

Photograph by Matt Buchanan.

I grew up with Macintosh computers, back when they were still called Macintoshes; it seems quaint and old-fashioned, now, that they were named after a fruit. The first Apple computer I used was a desktop, with a black-and-white screen that was taller than it was wide, like a sheet of paper. It's the only one of its kind I've ever seen. Apple always seemed like the black sheep, I guess. I'm not sure why my father chose that computer over the multitude of PCs on the market back in the nineties, but for a decade and a half, the majority of my family's computers—the newest and nicest ones—were always Macs.

As an outcrop and a consequence of this, the first computer I ever got, the first one that was mine, all mine—not mine-when-I-needed-it-for-school, not mine-when-my-parents-were-out, not mine-when-my-sister-was-busy—was an iMac G3, blueberry-coloured, a slight, few-years-late update on the original one. It was bulbous but it was beautiful, and it didn't have that shitty hockey-puck mouse that the first iMacs came with.

I'm only on my second desktop since then—a white G5, the one with the huge chin—but I also have a year-old MacBook Pro, and an iPod touch, which is my third iPod, and in a few weeks I'm going to purchase my first iPhone, the 4S. The start of my relationship with Apple, like the start of every relationship, was an accident. It owed everything to happenstance. But it hasn't lasted this long by accident.

Though he was never famous in his own right—wasn't in the tabloids or the gossip blogs like he was a real celebrity—Steve Jobs was a celebrity. Maybe not quite on Bill Gate's level, but he was a step up from Sergey and What-His-Name at Google, and more important than Mark Zuckerberg. (Yes, those are the only tech people I know.)

Steve was a singular figure. No one in North American culture, I think, has spent so many years getting filthy rich in or around the spotlight, without failing, without having any dirt thrown on him, without ever making a misstep. Kanye was rude to Taylor Swift. Britney shaved her head. Tom Cruise was a crazy, gay Scientologist. Mark and the Google guys wanted to usher in a post-privacy era. Even Bill made those commercials with Jerry Seinfeld. But Steve was kind of perfect, an untouchable golden boy, a—since the Cube, at least—Midas figure.

You don't need to look any further than the fierce anti-New York Yankees streak in our culture to know that people get tired of that kind of success fast, but Steve Jobs had a secret advantage that doesn't really exist in the sports world: no matter how successful Apple became, it would remain the underdog. The company's PC market share was always going to be a small fraction of the whole, so no matter how well its laptops and iPods and iPhones and iPads did, no matter how long its winning streak continued, Apple could always be painted as the upstarts.

It was a dishonest narrative, of course. Apple is actually the future of technology, while desktop PCs are almost-relics; they are slow-moving dinosaurs; early, unfinished versions of future iPads and iPhones. But for a decade and a half, Apple was the underdog, and so it was hard to begrudge the winning streak, even as it became one of the richest corporations in the world.

Jobs was a man whose success—no matter how many innovative, stylish ads Apple released—was forever corporate, the kind of man railed against at the Occupy Wall Street protests that he did not outlive. But he was a continually successful man in a corporate world peopled with people who succeeded only by percentages; he was a strange, fiftysomething phenom.

No matter how well Jobs did, he was always doing it under the shadow of Microsoft. He may have been a sanitized, capitalist robot whose every move was calculated, who was ruthless and scheming and endlessly working toward improving Apple's stock-market performance, who seemingly refused to give to charity—publicly, at least—but he was a man who put the Platonic ideals of quality and concept and aesthetics before anything else—before the boardroom, before the focus group, before the comment sections. His vision was the kind of thing that people dream of when they say "benevolent dictator," and it's not often that we see those.

Leave it to Steve Jobs, the eternal showman, to die the day after the iPhone 4S launch, prolonging the Apple conversation another couple of days and making it all the harder to be critical about the company. It's easy to joke about this stuff, to be nonchalant and clever, and to make light of how much we seem to invest in new technology. But Steve Jobs was a man for whom that technology was a part of life; a part of life we weren't going to avoid, no matter how jaded we pretended to be. We owe him for taking that part of life seriously—for refusing to compromise on the future.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org: