We Will Not Leave This Place

Everyone in Fernie, British Columbia knows the town is cursed. Why do we stay close to home, even in the face of endless tragedy?

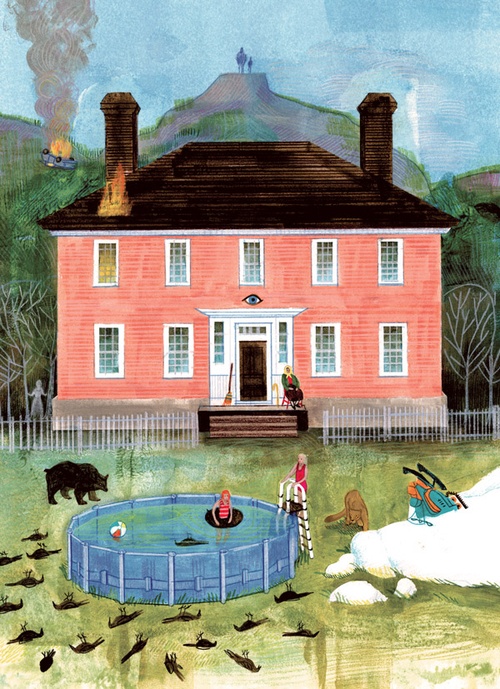

Illustration by Genevieve Simms.

We were the only people in town who had a pool, as far as I knew. It wasn’t special, just a faux-gesture of superiority, something that helped us pretend to pretend to be better than the town or the people in it. A meta-lark. My mother liked the pool, thought it matched the house, which we systemically misused. On the outside, it was a pretty, Georgian-style colonial structure, adjacent to the Fernie Museum; on the inside, it was a TV-for-every-room, shag-carpeted disaster. Together, the house and the pool projected to passers-by that we were on solid footing. We weren’t, but no matter—like so many things in our lives, the house and the pool were much better in the telling than in reality.

When I finally revealed the pool to my friend Nicole, I distinctly remember her saying, “That’s it?” Yes, that was it; an aboveground, hexagonal Canadian Tire special. Ugly and industrial-looking on the outside, and cold as Rocky Mountain hose water on the inside, because that’s what filled it.

In June, we bought the pool and started using it right away, even though the thermometer was still only topping out at fifteen, eighteen degrees. After several weeks of teeth-chattering dunks, my sister and I squealing our way through quick ins and outs, the surface sprouted brown muck that made our skin slimy. Only then did my stepdad finally invest in a filter and chlorine, which he dumped in without measuring.

By August, with the mountains around us on fire, the pool had finally reached its optimum temperature. I still strongly associate the sour smell of pool chlorine with the acrid smell of forest-fire smoke. I was thirteen. I went to summer camp for two weeks and came back tanned, first-kissed and totally over the pool. Not long after, fall descended in that quick, dark way it does at higher elevations. We forgot to cover the pool, and too soon it snowed. The mountains around us boomed with avalanches. The pool became a white top hat in the yard and then froze, developing cracks around the outside. In spring, when the thaw started, we noticed a black smudge under the pool ice; while investigating with a broomstick, my stepdad found a huge black crow, dead at the bottom. “Could have been worse,” my mom said with a macabre grin. “Could have been the neighbour’s kid in there.” We never went back in.

In the months that followed, the pool cracks widened. Late one night, the whole thing broke open, silently sending litres and litres of dead-bird water across the yard. In the morning, pieces of plastic and crow were spread across the grass. We tossed the detritus in the church dumpster across the alley, and a brown-grass crater remained where the pool had been. For weeks, we kept finding little bird bones. One came out of my dog’s throat with a heaving hack; another clogged the lawn mower irreparably.

The joke was that this kind of thing should never have happened in our Malibu mansion—the pool boy, Manuel, should have scooped out the crow right away. He would need a talking to.

A few winters back, when eight snowmobilers died in an avalanche forty kilometres from my hometown, many of their names sounded familiar. I’d never met any of them, but they might as well have been people with whom I grew up. The photos on the news were in familiar hues: the brown-green-greys of hunting apparel; the olive-skinned, red-bearded faces of men who worked at mills and mines, the kind who passed with a wave and a cloud of dust on the back roads of my childhood, who knew an uncle, worked with a cousin, dated a friend.

It was not only their lives that looked familiar, though; it was also their deaths, awful and desperate and common. Like so many happenstances in the area, this latest incident reflected a local tendency toward the hair-raising, the profane, the liminal. The worst that can happen when man and nature collide. Falling off the side of the mountain, getting crushed inside it, crashing into it. Hitting a moose so hard it bounces off your windshield and crumples the compact sedan behind you. Kicking a dead raccoon off the highway, fed up after weeks of driving past it. Kicking a black bear in the ass on a dare, running like hell. Burning your jeans jumping over a bonfire. Losing a testicle jumping off a cliff into a lake. Losing an arm under a falling truck, waiting two hours for your buddy to drive up the road and find you. Finding a dead bear in your cabin after a long winter, its monstrous body bloated from eating whole cans of beans. Rescuing your toddler from a cougar’s mouth in your own backyard. Knowing the moment it happens that your twin brother is dead, later hearing he’d fallen out of the back of a pickup truck. Being so wasted drunk that you crash your car going 140 and forget that your best friend is inside it, walking away while he burns up alone on a stretch of highway cut out of solid rock. Spending your last moments thinking about your infant son in his new hunting clothes while your lungs fill with snow.

Growing up, I did not question the place I was from. Nor did I question the extreme ways in which we all lived and died. It was only after I left that I grew fearful in retrospect, gritting my teeth as I drove through blizzards instead of laughing and singing along to the radio. Wondering about my family’s safety over there, watching hawk-eyed for deer on deerless roads, listening for news reports of avalanches. Thinking everyone I grew up with must be mad or stupid for staying.

Lately I’ve drawn perverse enjoyment from reading judgmental literature about where I’m from—articles about the dead snowmobilers, mainly (What possesses people to hurl themselves down virgin snow on heavy machines?), but other stuff, too. The Robertson book, though, was unintentional. I bought it because I recognized the mountain on the cover, in the same way I recognized the faces of the dead men; they are of a type, written in my DNA. Mt. Hosmer, the Ghostrider. I didn’t even think twice, just grabbed it off the shelf and paid.

Leslie A. Robertson’s Imagining Difference: Legend, Curse, and Spectacle in a Canadian Mining Town is a thick tome; it must be her thesis, in one of the -ologies. It’s tough to slog through, but I read it cover-to-cover, making extensive notes toward no real purpose other than curiosity, or searching for mistakes. Like a good small-town girl, I called my mother and asked about this woman, who states in her introduction that she is “the fourth generation in my mother’s line to live in Fernie.” My mom confirmed that she remembers the Robertson family, but not much else.

In her book, Robertson uses the story of the Fernie curse to show how people in the town “imagine difference,” be it cultural, racial, religious. She paints a compelling picture of the people and the place, but misses the one difference I think truly matters: the difference between the people who stay, punishing themselves, and the people who go, misunderstanding the punished.

The curse story, or the version I learned: way back before the Elk Valley was occupied by European miners, when only the Ktunaxa people lived in these hard-to-navigate mountain passes, a man named William Fernie came across an Indian band while looking for gold. The chief’s daughter was wearing big black rocks around her neck—coal. Fernie promised to marry her in exchange for information about where the coal came from. The chief told him and, of course, Fernie ran off, breaking his oath. Today, when the light is right, you can see the looming shadow of a horse and rider on the side of Mt. Hosmer. This is the chief, perpetually searching for Fernie. The maiden walks beside him.

As a result of this betrayal, the story goes, the Ktunaxa forever cursed the town of Fernie and the surrounding area to suffer floods, fires and all manner of disaster (and, lo, its hockey team was cursed to be called the Fernie Ghostriders). “After the turn of the twentieth century, residents of Fernie experienced an alarming sequence of events that drastically shaped historical consciousness into the present,” Robertson writes. “It is during this period of time that I imagine the story of the curse gained its narrative power.” She goes on to list a series of dates and events familiar to nearly every kid who grew up in the town, myself included. Floods: 1897, 1902, 1916, 1923 and 1948. Fires: 1904, 1908. Frequent mining disasters.

In the late sixties, the mayor of Fernie and the chief of the Ktunaxa smoked a peace pipe to lift the curse. No more fires, but the river broke bank more than once when I was a kid. I can still conjure sandbags and stinking basements. “The chief must be mad,” my babysitter said as the floodwaters rolled in. She laughed and moved everything in her cellar up into the living room.

My paternal great-grandparents first came to the Elk Valley in the 1930s. His name was Domenico, hers Vittoria. Domenico was lured from a troubled patch of poor Italy, along with hundreds of others, to work the Crow’s Nest Pass Company mines outside of Fernie. Like the others, he was granted “free” passage, and room and board in company houses; the cost of these amenities was subtracted from his paycheques. He arrived with his young bride-to-be, who was only fifteen at the time. They married in Fernie, and Vittoria signed the marriage certificate with an X, since she couldn’t write. She gave birth to eleven children, eight of whom lived. (The youngest would become my grandfather.) Vittoria died at thirty-eight from breast cancer; her only known relative, a brother, had died a few years earlier in one of the area’s many mine explosions. “Between 1902 and 1967, 226 men were killed in the mines at Coal Creek, Morrissey and Michel-Natal,” Robertson writes. I used to go into the graveyard with my grade-three class and make pencil tracings of the pretty miners’ graves, decorated as they were with Victorian curlicues and serifs.

At various points the coal industry flattened and revived, usually due to Japanese and Chinese interest in the stuff. There were stretches when the mines shut without warning, when the men came to work in the morning and were turned away. Then there were the days after disasters, the burying and the digging out. In there were many opportunities, and plenty of impetus, for people to leave, to go somewhere where the going was better. They rarely did.

For three decades, my family lived in Michel-Natal, twin towns that no longer exist—the province tore both down in the sixties and seventies. By then, the company-owned houses, built around the turn of the twentieth century, were in an advanced state of disrepair. At least, they were on the outside; the identical houses were coated with mining dust, which also stained sheets on the line, blackened children’s faces, mutated everyone’s cells. On the inside, though, most of the homes were immaculate, maintained by the wives while the men were away in the mines. There was no running water, even at the time the buildings were demolished. My father and his twin sister spent most of their childhoods without plumbing, racing to the backyard outhouse in every kind of weather, drawing drinking water from a pump.

By the sixties, the province had finished building nearby Sparwood, which they proposed as a more pleasant entrance to British Columbia from the Alberta side. The people who lived in Michel-Natal say they were told to move, to give up their cheap company leases in exchange for a mortgage in Sparwood. My grandfather, a butcher, took up the offer twofold, opening his shop in town and buying a house there. Others were less excited. I heard about one woman who sat in her home, the door marked for demolition, until every building around her was gone. Everyone she knew, her entire community, had left, and yet she stayed. A cadre of women, her friends and relatives, finally came from Sparwood and pulled her out. She reportedly screamed and cried in Italian the entire time, clutching a mano cornuto—old-world protection against the evil eye. I don’t remember where I heard this, but I don’t doubt that it is true.

From 2006 to 2008, I worked in a bright, airy office in Vancouver’s Gastown. My job was to recruit “citizen journalists” to a “news site” where they could post their versions of events, without anyone editing or filtering their contributions. The idea was that the news belongs to everyone; the reality was that journalists are paid for a reason.

Nonetheless, some diamonds appeared in the rough, including a former National Guard soldier who had spent nearly two months on the ground in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. I helped him edit his confessional, devastating pieces of writing for better public consumption. A few of the details eventually made it onto CNN.com, including confirmation that the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s disorganization reached manic levels in the days after the storm—that fresh water sat oxidizing in huge tanks for nearly a week after the hurricane hit, simply because officials couldn’t figure out how to get it to people without triggering a riot.

A story the soldier wrote that didn’t make it onto CNN: one day on patrol, another National Guardsman he knew rounded a corner to find a man raping a young girl. The guardsman told the man to stop, but the man refused. He put a gun to the man’s head; he still refused. Finally, the guardsman shot the man and left him there, bringing the girl back to headquarters with his unit.

One day during a boat patrol, the soldier told me, he passed a house in high water. (He also passed Sean Penn, on a boat headed in the opposite direction.) On the mouldering porch sat an elderly woman with a shotgun. By the markings on the door, the soldier could tell there was a dead body inside. He tried to get the woman to leave, but she refused. He begged, offered her food, blankets, his cellphone. She merely shook her head. “You can leave, if you want,” the woman said. “I live here.”

At one point, the soldier said, several FEMA boats sailed around, attempting to take people to buses that would bring them to paid accommodations in Baton Rouge or Houston. Many refused.

All of us in the office shook our heads in wonder at this, the desire to stay past the point of no return, to endure death, rape, hardship when nothing about your home is your home anymore. There are reasons, of course: poverty, stubbornness, sadness, madness. But these seem somehow inadequate. Mountains crush us and we keep living on them. The earth tries to drown us, it opens beneath us, it lights us on fire. Our breasts rot from the inside out, our children’s lungs grow black, and yet we don’t leave. New Orleans, Haiti, Japan. Even Fernie.

Last year, I got really into the show Treme, about post-Katrina New Orleans. It was all-too-familiar: the tight-knit community, the survival instinct, the determination to stay. The opening credits seemed, at first, to be set against oil-painted backgrounds; only by the third episode or so did I realize that these were photographs of walls, watermarked and covered in blossoms of black mould from the flood. I oohed and ahhed at the brilliance of this choice.

I tell the stories about the National Guard soldier when I speak about the show, to friends with warm homes and happy, unremarkable existences not unlike mine. We shake our heads. “Why do people live in places like this?” we ask one another, rhetorically. We do not give much thought to the fact that we are sitting on a couch in Vancouver, on top of a fault line poised to swallow us all. Tsk, tsk, we say.

In the first episode of Treme, a character called the Big Chief wanders up a filthy road. He has just returned, three months after the flood. A neighbour spots him and shakes his head. “I knew you’d come back,” the man says to him. “I knew you’d never leave,” replies the Big Chief.

The curse story I remember most: the first fire, in 1904. A family in the Elk Valley woke to their house burning around them. They somehow escaped and jumped into their well, seeking shelter. Instead, they boiled alive. For some reason I will never understand, a rather large painting of this event is on display at the Fernie Heritage Library. There is even a baby involved, a swaddled infant, clutched by a woman as she runs from the fire. I once watched an elderly Italian woman cross herself in front of it.

“Calabrian women told me about villages threatened by burning logs in the sky, or earthquakes caused by slips of faith,” writes Robertson in Imagining Difference. “Their stories are filled with faith-promoting miracles of saints whose statues are inextricably bound to the destiny of each small village.” Robertson also mentions “the miner’s mark,” a smudge of protective coal dust worn on miners’ shoulder blades and carefully avoided by wives’ soapy hands during bath time.

In 1967, a great-uncle of mine and many others like him exploded in a coalmine, which was close enough to my family’s doorstep that black dust blew through the slats and doors slammed against their panes. Marked or not, he was gone. Then the siren started. “For the wives and children of early miners,” writes Robertson, “anticipation of the dreaded emergency siren was a daily burden.”

My grandmother—my father’s mother—married a miner when her first husband, the butcher, died of a heart attack. She later succumbed to a body full of cancer, having spent her whole life in the shadow of a mountain that poisoned her. Two years ago, a friend’s stepfather died when his truck slid off the side of an open-pit mine. He’d driven around that same mine for nearly twenty-five years without incident. Held up against ends like these, the dead snowmobilers’ fates seem set in stone.

It’s the first parade in New Orleans since the storm. An eight-piece called Rebirth Brass Band is about to be paid for playing in the procession, each musician getting a little under $200 for his efforts. The bandleader protests. “Man, look around,” his employer says. “Look at this damn place!” The bandleader looks around; the shot widens so we can too. In the shadows, black splotches decorate the walls, Pollock-like. I think about the smell. “How much water y’all get up here?” the bandleader says, gently.

“Shit, you see this line over my head. Six? Six and a half?”

“Look, I feel for y’all. But less than two hundred a man? That shit ain’t right.”

In the next scene, the band makes its way through the Treme neighbourhood, waking local radio DJ/musician Davis McAlary, played with charming, manic-slacker energy by Steve Zahn. McAlary springs out of bed. He listens to the horns. “That sounds like the Rebirth,” he says.

Before the end of the show’s first season, McAlary is teaching the daughter of a local professor how to play piano. The professor, played by John Goodman, has become a celebrity of sorts, ranting on YouTube about the country’s indifference to New Orleans. Late in the season, after seeing his city rot beneath him, unable to write the novel he’s promised to his publisher, Goodman’s character commits suicide. This, in spite of a happy home life with his wife and daughter. On a Treme blog, fans debated this plot point heatedly. One commenter suggested it was bad writing: why would a man with a family simply kill himself like that? Another fan responded: if you were from New Orleans, you’d understand.

Our old house with the pool was undoubtedly haunted—lights turned on and off without warning, women walked by open doors in the night and vanished, voices rose from empty rooms. I was studying at the dining-room table one night when I heard my sister and mother come in the front door, remove their boots and prepare dinner in the kitchen. When I got up to say hello, I remembered they were at a hockey game. No one was there. Whether we believed in ghosts was not the question, as we were a household of Mulders with no Scully to convince—witnesses with no need to testify. Instead, the question was what would happen next. After the crow in the pool, other birds kept flying into our windows, dying in liquefied heaps that we eventually stopped cleaning up.

The house was built in 1908, right after the second Fernie fire. The town was rebuilt around it, this time in curse-proof brick. In the century before we owned it, the house belonged to a doctor, who operated it as home for nuns (and, supposedly, unwed mothers). A childless couple bought it after that, and lived in it until they died. When we moved in, there were still dresses and suits hanging in the closets, their collars and armpits stained yellow. When we tore out the porch to build an addition, we discovered the walls were filled with crumbling old newspaper. One page showed people lined up for assistance after the fire.

These days, the house is a bed-and-breakfast, redone in its original turn-of-the-century style. I once dropped by and asked to look around, explaining to the owners that I had lived there. I mentioned the pool. The new owners—Albertans, for Christ’s sake—closed the door in my face. I instantly hoped that the ghosts of crows, avalanches and floods would visit them in the night, and I spit on the doorknob. Like an old Italian woman in a headscarf, I cursed the already cursed—those who chose to live in this place, those who did not know which fates they were tempting. Then I walked through the backyard and out the gate. The sky was bruised and cloudy that day, so the ghostrider of Mt. Hosmer was nowhere to be seen; the mountain stared down, empty and impassive.