In This Field, This Place

One of two second-place stories from Maisonneuve’s 2012 Genre Fiction Contest. This year’s theme was science fiction.

And then there was Anna and me. Anna'd shaved her head early on, leaving behind a trail of staccato nicks that threatened the surrounding whiteness of her scalp. I still found her beautiful, even though, it was true, there wasn't much left to compare her with. S., How, Jo, Billy and Eva. They were our world now. And they too had taken on the gaunt hairlessness that Anna had. I had kept my own hair, had chosen it as my "touchstone."

We'd buried the mirrors early on, but we still walked around camp like shadows, afraid to catch our reflections in some still-there water tank, or the large sinks that waited in front of the mess hall, or the lake's dark expanse. I had argued for the importance of some form of self-reflection, some measure of accountability, some way to remember I am here, but Billy'd said of mirrors that they contaminated perception—they'd been among the biggest culprits. And that had been that. Period.

We'd agreed. We'd all wanted to agree. We'd all needed to. During one of the icebreakers our first night at Procamp—which felt like years ago now—Stanley Litmus had asked us to list four of our main attributes and Billy had said "born leader" twice. Eva had the hardest time of it. She'd been beautiful in a serious way in the beforeland, maybe even a model or an actress. During the renaming ceremony, she'd said, crying, "Everything's in a name," and Billy had said in her spitting way, "That's fucking right," and it reminded us that if there had been a safe way to peel the skin off of herself and change into a new one, Billy would have gladly done so. Unlike the rest of us, there was nothing before Procamp that she had the slightest inclination to hold onto. We'd agreed, finally, that Eva could keep her name, as long as she didn't forget its oppressive past.

At night, Anna and I clung to one another and it was then that I thought I knew what it was all for. I kept my face as close as I could to hers. I memorized it all: the green eyes and their short lashes, the slight widening of her nose a few centimeters down the bridge, the blond hairs above her lips that skipped with light. It was strange to think of how quickly that face had become embossed in me. I was worried that it would be taken away just as swiftly and I'd be left to look at what lay beyond it: the tent and the field in which the tent had been pitched, the camp beyond the field, the acres upon acres of woodland that separated this place from all of the others in the world. Isolation breeds desire. It had been one of Procamp's mantras. My mother had sent me the brochure earlier that spring with a post-it: "re: your future." It had stung, to have my own mother think me fit for Procamp. It had always seemed the stuff of a different kind of family, a different kind of woman.

After all, I'd been in the right range for IQ and Attractiveness and Fertility and Income. But you never do think you're one of them, until you're thirty-two and unpaired and stuck. That's when the compounds are no longer the stuff of parental threats to their misbehaved daughters, but a real prospect, a potential future. There'd been demographic factors working against my cohort, against me, that was true. Gender scarcity. I think that's what they called it. The pictures I'd gotten in the mail from the

Department of Reproductive Regeneration that year had seemed more like a punishment than a viable option. The algorithm had set me up with obese men twice my age, who'd already had families, who'd lost wives to breast cancer and uterine cancer and cancer of the brain. I wondered if there was something about myself I didn't know. Some undesirability that the psychological and medical tests administered when I was eighteen had revealed.

Procamp promised Falling in Love the Old-Fashioned Way and it had delivered, I suppose. Anna and I had been put on the same team for capture-the-flag. Men vs. Women, of course. (Stanley Litmus based all of our activities on survivalist principles, proven necessary for efficient heterosexual coupling.) But I'd already had a sense of something off in the men. Something repellent about them. We all had. There was the matter of their hands, which seemed like boys' hands, tapering off at the fingernails so that the tired things appeared to live in fearful retreat. And then their eyes, which lingered endlessly away from the women's, not shyly, but with palpable disinterest. They'd all been balding and wide-hipped and uncannily fair. I had been drawn immediately to the soft way Anna touched my arm, and the difficulty she had in finding the appropriate resting place for her long dirty blond hair. Just as soon as she had tucked it neatly behind her ear, she'd lift the whole heft of it and carefully place it over her left shoulder, then look around shyly to see if anyone was watching the ritual. She was used to being looked at, and so I had the urge to look down, not to stare too long.

"We've got to keep our numbers up!" had been Stanley Litmus' cheerful defence of the mandatory inseminations. Yoon-Jin, his first victim, had spent days in her bunk and we'd tried to build her a shelter by hanging sarongs and sheets around the bed, as if we were fourteen and playing Arabian princess. Anna's insemination had been particularly brutal. She hadn't wanted to say much about it in the aftermath, believing that the more words she contributed to the retelling, the more alive the thing would become. She'd been a poet before—a good one—invited to read in other countries, at their universities and in their festivals. She'd told me that four of the men had sat on her limbs, while Stanley had repeated, thrusting, that the numbers could not lie, that 100 percent success rates didn't come from playing softball with pansies!

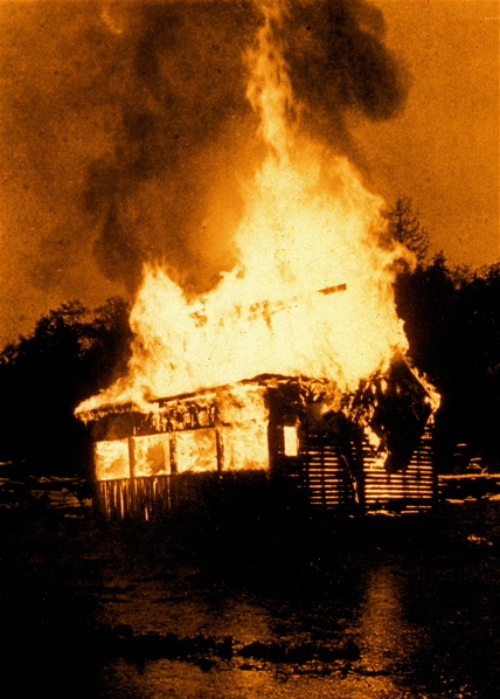

We locked Stanley up first. Then we all gathered and watched the fire consume his cabin hungrily. He'd been the easiest to trap and then throw in the fire, the one whose scream had quickly turned into the most girlish, unraveled complaint. We got to him before he'd had the chance to get to me. That was what they all kept reminding me. But I'd been on ovulation watch earlier that week, and I couldn't help but wonder why I hadn't been chosen. I knew it didn't matter anymore now that all the men were gone, now that Stanley was just the charred memory of a despot, but I couldn't help myself. Billy had insisted I throw a match on one of the men's cabins: "Your heart needs to be in this." And I had done it, hoping it would help all of it—including the doubts about my essential suitability—disappear for good. We'd all wanted for a long time to love and be loved the way we thought we ought to.

Later that first night, we'd burned Anna's hair on the bonfire and there'd been something almost too alive about the flames lapping the soft glow of the ponytail and then for a flash the hair had taken on the starched quality of straw and just as quickly had vanished into the embers. For god knows what reason, we had all found this very funny and we'd laughed quietly at first, then more loudly, relieved by the sounds we were making—their reminder that we were still here. Although, it was true, that in this field our laughs sounded tinny and sad, emerging as if from a hollow and faraway place.