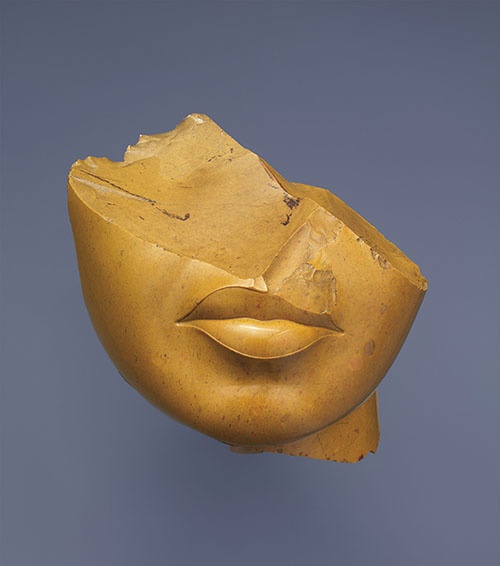

Fragment of a Queen’s Face Egypt, ca. 1353–1336 B.C. Yellow jasper

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fragment of a Queen’s Face Egypt, ca. 1353–1336 B.C. Yellow jasper

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Blue Girls of Summer

Translation of an excerpt of Les filles bleues de l’été Published by Cheval d’août éditeur, 2017, pages 13–15. Translation: Melissa Bull.

When we left, Chloé had just come out of the clinic where they lock up women who want to harm themselves. A small community chained to their fears. Not knowing better, I imagined thinly stretched women dragging their feet along a white floor. But Chloé wasn’t, as the rumour had it, crazy. She had just gotten lost for a moment. Chloé was beautiful, somewhat like a little animal, with her large, lively eyes and her dark hair. It was my idea that we live together, that we leave—she to grow with the other longues tiges, and I to watch her. I managed to reach her parents by telephone, in the village where we were born. They sent me the keys to the cottage in the mail.

Our childhood cottage. This place had seen us grow. On this earth, my friend would regain her strength. Time to make up for: with the embers of the past, stoke a fire as big as the sky.

I went to pick Chloé up. The last time I had seen her outside of the rest home was three months earlier. I thought of it again, in the car, choked up by an image: my friend as thin as the sound of rainfall, her eyes riveted to blank space, light-years away. This wasn’t my Chloé; this one was frightening. It always took a certain amount of time for my voice to reach to the depths of her distress. A short time before her hospitalization, I asked her why she hurt herself so much. Chloé wanted to shift the pain from her skull to her skin. She thought it would be easier.

I thought it wise to alert her parents. A kind of treason, but it had to be done. She didn’t hold it against me. They’d had her admitted to the clinic. Since they were away, I was the one who had to drive her there. Early last spring, I took her away from her life.

We’d crossed the city in my car until we arrived at the little building. On a pink sign planted in the lawn was the image of a woman standing in the heart of a lotus flower. A word game, leading those who came to believe that they would come out changed.

Three months without Chloé’s soft glances to accompany me in my labyrinths of cedar and love, but now, I was coming to get her. When the time came, she left the house with her bag against her chest. She squinted as if she had not seen the light for a long time, maybe ever. I could see very well that there was still trouble in her head, but I didn’t say anything. I wanted to bring her into summer.

As we pulled away, Chloé watched the clinic melt into the distance. We had months to catch up on, but we didn’t say anything to each other. Her eyes were heavy with fatigue. I took her hand. Over the telephone, her parents had explained the idea of the cottage to her, enunciating clearly, the way you speak to the dead. Chloé’s mother hesitated when it came time to say the word “disease,” which she replaced with “condition.” In the car, quietly, muffled by the music and the air conditioning, I spoke to her of our escape. I described my plan to her, and the lake shimmered beneath our eyes.

Something stirred beneath her imaginary corset.