Crude Tactics

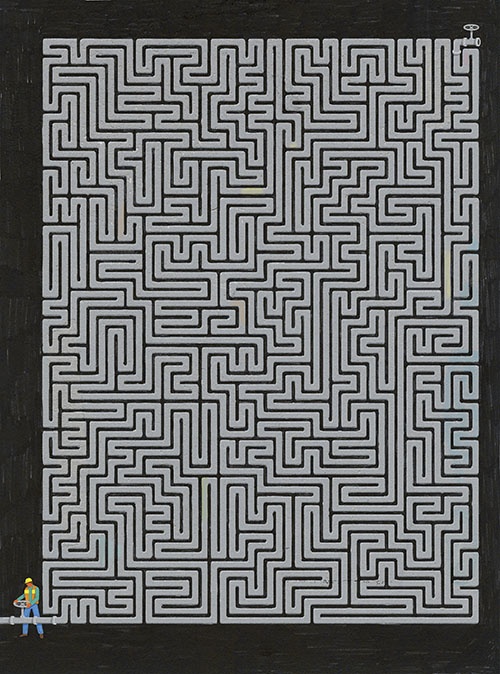

Behind the scenes of the Trans Mountain pipeline fight.

It was a cold spring morning in 2017, and thirteen bureaucrats from across the country were scheduled to gather in Ottawa. A senior among them would lead the group in an ice-breaker: “If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you want to have with you?” It was a fitting question for the $7,500 workshop, which would delve into a unique Canadian riddle: energy policy, beset with its own tough choices and zero-sum dilemmas.

At the time, the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, meant to carry crude from Alberta to the BC coast, was on its way to construction. There were few hints it would become anything more; the topic was so uncontroversial, in fact, it was eventually dropped from the workshop’s schedule. Few in that company of thirteen likely expected that in just over a year, Trans Mountain would spiral into a quagmire splitting the nation.

Today, the fight over the pipeline is not only a defining moment for Canada’s oilsands, but a potential turning point for Indigenous–Crown relations and Canada’s environmental movement, not to mention a key to political survival for two provincial NDP governments—in Alberta and BC—as well as the federal Liberals. Those high stakes are reflected in internal documents obtained by Maisonneuve under access-to-information laws, which give a behind-the-scenes peek into new government strategies, including Ottawa’s attempt to dial up its overtures towards the pipeline’s opponents. Meanwhile, environmentalists have been trying out their own innovative forms of protest. Canada has fought over pipelines before, but never like this.

In early June, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau arrived with rolled-up shirtsleeves in Sherwood Park, near Edmonton, to shake the hands of Kinder Morgan’s blueoverall-clad roughnecks. It was a classic grip-and-grin, for Trudeau’s government had just cleared a major hurdle for the Trans Mountain project. “Moving forward on this pipeline gets us to a new market,” Trudeau told reporters, echoing the sentiments of an Alberta-centred oil industry almost desperate for fresh export routes— Canada’s vast deposits of crude are largely landlocked, yet its pipeline capacity is low, meaning high transportation costs cut into profits. “We lose about $15 billion a year,” Trudeau said. The site, with its snaking pipes and sheet-metal structures on dirt ground, was a fitting venue for the photo op. It was, as the prime minister called it, “mile zero,” where the original Trans Mountain begins. Due in 2020, the expansion would twin that pipeline and nearly triple its volume, lifting prices, boosting revenue and creating jobs—all of it, Trudeau underscored, in the “national interest.”

Trudeau was squinting under the midday sun, but he could no doubt see the protestors directly in front of him, beyond Kinder Morgan’s fences. One had an upside-down maple leaf on her shirt; she wasn’t buying what he was selling. They, along with the BC government and some municipalities, oppose the pipeline, concerned about spills and Big Oil’s carbon footprint. Their goal is shared by many First Nations near or along the pipeline route, who denounce what they describe as an inadequate approval process for a project that could adversely affect their ways of life. Another protestor carried a sign featuring a clown-like portrait (ruby-red lips, sheet-white skin) of the prime minister: “Kinder Morgan Employee of the Month / Justin Crudeau.”

The saga has raged on protest grounds as much as in courts and legislature halls. In April, Kinder Morgan decided it had had enough of the opposition, suspending the project; to save Trans Mountain, the federal government bought out the pipeline shortly before Trudeau’s Edmonton trip. But the matter is far from over. Instead, it’s now simply the government’s to deal with, especially when it comes to one key issue: Indigenous rights and the federal government’s duty to consult. In 2016, Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline was effectively quashed when a judge ruled the government had not properly consulted the First Nations that could be potentially affected, an obligation under the constitution. Now, though the government has made efforts to improve, Trans Mountain has also ended up in court over the same issue. The decision, due days after this issue of Maisonneuve goes to print, threatens to kill the entire project.

Bureaucrats anticipated this roadblock. In spring 2016, Natural Resources staff quietly warned the government that Kinder Morgan’s boast of Indigenous support was not what it seemed. The company said it had agreements with First Nations along most of the Trans Mountain route, but that didn’t reflect reality, the then–deputy minister wrote in an internal briefing note. “There are a number of instances where several groups claim a traditional territory, but the proponent has only come to an agreement with one.”

When asked about the matter by Maisonneuve, Kinder Morgan reiterated previous comments that it had arrived at forty-three benefıts agreements with First Nations along the route. The government’s “Crown list,” however, includes a total of 115 Indigenous groups that need to be consulted, according to the Natural Resources briefing note. While there has long been dispute over whether each group needs to give full consent for Trans Mountain to happen, any opposition could nonetheless hurt the project. And, even before Trudeau’s government bought Trans Mountain, what hurt the pipeline could hurt them, too—if Trans Mountain tanked, it would damage the Liberals’ chances in the next federal election, likely to take place in 2019. It was against that backdrop that, in fall 2016, then–Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr caught a 6:50 a.m. flight west from Ottawa to “make progress in consultations.”

When Carr landed, he toured Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet, a busy urban waterway, but also a coastal fjord formed during the last Ice Age, whose shores several First Nations have called home for thousands of years. He was to meet the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, which had commissioned its own scathing environmental report on Trans Mountain and is among the most prominent plaintiffs in the multi-party lawsuit against the project, punching well above the weight of its population of six hundred. “It’s my life, and I won’t stop at anything to oppose it,” says Councillor Charlene Aleck, a Tsleil-Waututh spokesperson.

While Aleck says her First Nation is focused solely on stopping the pipeline, the fight also touches on some broader issues.

“It has uncovered how the government treats First Nations people,” she says. “First Nations rights over territories, land use—there are so many things that are tied into that.” How the federal government handles the matter could shape the Indigenous–Crown relationship for years to come.

Internal Natural Resources files show Carr began his meeting with Tsleil-Waututh’s chief, Maureen Thomas, by participating in a spiritual cleansing ceremony so that both would have “clean and open hearts.” After that, the pair donned blankets to ward off evil spirits, and signed an engagement protocol detailing the rules for the government’s consultation, a document over which both sides had laboured for three months. Outside the ceremony, however, Tsleil-Waututh says it dealt mostly with low-level bureaucrats, even as the federal government had promised a level-footing “nation-to-nation” relationship. It made the nation feel “like a checked box,” Aleck says. “If you were to propose to put big machinery in my backyard, but [say], ‘Only speak to my kids’—you see what I’m saying?”

Carr did, however, bring a promise of money in the text of the engagement protocol. Canada has long paid for costs Indigenous groups incur in consultations—including expenses associated with attending meetings and hiring experts—a figure previously capped at $150,000. For Tsleil-Waututh, the government planned to give more—$400,000, according to a briefing note prepared for the trip. Upping the price went against the department’s regulations, but the note said the rules had been changed so that the move could go ahead. While its authors did not specify the reasoning, they wrote the protocol would be “consistent” with the Liberal government’s endorsement of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

In changing those rules, Natural Resources more than tripled the maximum amount the government can pay, bringing it to $500,000, a move made with no announcement. At the time, the government also separately pledged more than $1 million to Tsleil-Waututh for various environmental projects, including forest restoration and a new internship. The government made similar arrangements with other nations opposing Trans Mountain, another briefing note shows.

Natural Resources spokesperson Samuelle Menard says that the funds it has dispensed to Indigenous groups are “fair and proportional” to a project’s risks, and that Tseil-Waututh’s costs reimbursement was determined based on Trans Mountain’s “close proximity” and “potentially important impacts.” The environmental funding, meant in part to create jobs and spur economic growth, would help to “facilitate informed Indigenous participation” in resource development.

But it also seems clear the government increased the funding to try to achieve its Trans Mountain goals. How quickly the government went about “upping the ante” shows how sensitive it is to the fact that has a lot to lose in this battle, says Richard Johnston, a professor of political science at the

University of British Columbia. “They wanted [Trans Mountain] to happen,” he says, “or at least, they did not want it to not happen for reasons that can be blamed on them.”

Still, not many minds were changed. Ottawa never secured a yes from Tsleil-Waututh, for example. “This is the federal government’s job, and we as First Nations shouldn’t have to be thankful,” Aleck says about the reimbursed costs. In fact, things appear to be getting tenser; while Tsleil-Waututh has long considered only legal opposition to Trans Mountain—and still does, Aleck stresses—civil disobedience may not be out of the question.

However rare it is for elected officials, two federal parliamentarians have already been arrested at Trans Mountain protests, and the sixty-six-year-old mayor of Burnaby, BC, has said he is prepared to suffer the same fate.

Despite the opposition, the government approved Trans Mountain in November 2016, and the consultations stopped—the matter was considered settled. Half a year later, however, investment bank analysts started writing clients doom-and-gloom emails about Trans Mountain’s future. The BC NDP—long in opposition to the provincial Liberals, and also opposed to Trans Mountain—was on the cusp of taking power after a watershed election.

A less-publicized problem also loomed. The Houston-based Kinder Morgan wanted to spin its Canadian subsidiary into a separate publicly traded company, in part to raise money for the $7.4 billion Trans Mountain expansion. Greenpeace environmentalists took note, and in response they used, for the very first time in Canada, an unusual tactic to sabotage the move. Combing Kinder Morgan’s mandatory disclosure papers for the initial public offering, they concluded the company had been “very deficient” in informing investors of business risks such as global efforts to combat climate change. The company was projecting oil consumption too bullishly, forecasting plentiful future profits, Greenpeace said. In an unprecedented move, the organization complained to the Alberta Securities Commission.

The commission never responded to Greenpeace’s arguments, but soon Kinder Morgan filed new disclosure papers that included the risks the organization highlighted. “It was a validation that it was a good approach,” says Alex Speers-Roesch, the head of Greenpeace’s oil campaign. When Kinder

Morgan did debut its Canada stock—just after the BC election and Greenpeace’s IPO attack—it was underwhelming, dropping to as low as $15 from an original target of at least $19 per share. The company was worth hundreds of millions less than it hoped—a “less-skewed valuation,” in Speers-Roesch’s words.

The previously unthinkable happened a few days later: what appeared to be the first delay in Trans Mountain’s schedule. In an internal memo, a top-level BC official noted that the company planned to start construction at a marine terminal in the province in August. Yet, publicly, Kinder Morgan said work would begin only in September. It’s unclear what caused that discrepancy, but the apparent delay would be the first of many. The company declined to comment on the issue.

But that briefing note wasn’t all bad news for Trans Mountain. BC public officials had watched the campaign-mode NDP leader John Horgan make promises to “use every tool in our toolbox to stop the project from going ahead.” In that same note about the apparentdelay,theauthorlaidoutalaundry list of legal obstacles that seemed likely to make Horgan’s campaign promises impossible to fulfill.

According to the briefing note, BC’s leaders needed to honour a deal the previous government had made with Kinder Morgan to “have a timely and efficient regulatory and decision making process.” Civil servants reviewing the project’s local permits “cannot slow their decision-making for any improper purpose and cannot be fettered,” the official wrote. In addition, Canada’s constitution gives the federal government jurisdiction over pipelines, and “the province would be limited in its ability to prevent the project.”

The note would have come as a blunt reminder: “This is the reality,” says Lori Williams, policy studies professor at Mount Royal University. Premier Horgan was caught in “a difficult position”; to govern, the minority NDP had struck a deal for Green Party support. But the price of that Green support was, in part, making good on its anti-Trans Mountain campaign pledge. Ironically, the pledge also caused the party to clash with its counterpart in Alberta, where support for the provincial NDP relies, in part, on the pipeline’s being built.

BC’s environment minister, George Heyman, says that only after forming government, “we learned that other than challenging the decision from the federal government to approve the project in the court— which we have done—we do not have the power to unilaterally stop the project.”

In July 2017, the same month the BC NDP officially took power, its posturing appeared to soften. BC’s attorney general, speaking on a radio show, asserted that the government wouldn’t block local permits for the pipeline. And the party’s messaging shifted: it ceased saying it would “stop” Trans Mountain, and began, instead, to say that it would simply “defend BC’s interests.”

This April, just before Kinder Morgan suspended the Trans Mountain project, internal briefing notes to Natural Resources’ Carr began to home in on public perception of the government’s energy strategy. Words rarely used in the context of government bureaucracy cropped up, among them “narrative” and “storyline.”

The federal Liberals, while backing resource development, have also made big moves to combat climate change. This reflects not just a commitment to that issue, but also the party’s long-held view that public support to build a pipeline comes from having a good environment policy. Developing oil and gas and protecting the environment “are not mutually exclusive goals,” says Menard of the Department of Natural Resources.

But the strategy wasn’t yet working well, Carr told politicians and businesspeople this April in Fort McMurray, according to meeting notes. “We’ve heard that the storyline of how oil and gas fits into Canada’s energy transition isn’t well articulated,” he said in prepared remarks to the town’s politicians and, again, to its chamber of commerce.

Though Menard says the government has sought across-board input at “a number of stakeholder engagement fora,” in the April meetings, it appeared to be focussed on those who support resource development.

Carr, who moved to a different portfolio in July, asked those he met in Fort McMurray how better to tell the Liberal story—that transitioning off fossil fuels goes hand-in-hand with developing natural resources. Then he sought advice on the same issue from the head of the big US oil producer ConocoPhillips, which takes part in a government working group. “I would welcome your feedback,” Carr said, “on how we strengthen this narrative.”

Ethan Lou’s writing has appeared in Maclean’s and the Walrus. He is a former journalist with Reuters.