Grave Decisions

A new generation of mourners wants to strip funerals back to the basics—but what are the basics?

When Rob Mark’s father-in-law died suddenly in a workplace accident, Mark and his wife were in shock. As they grieved, something else began to dawn—they were going to have to go to a funeral home, and no matter what their budget, it wouldn’t come cheap. And they were right. “It felt like I was buying a used car from a dodgy dealership,” Mark recalls.

His father-in-law had hated flowers, but the funeral director pushed flowers on them anyway. He added up the costs on paper, and the footnotes in his head—around $400 for “a flower arrangement that I could go to a florist and buy for seventy-five bucks” went on the list, and around $300 for a snack tray “I’m pretty sure you could have bought at any grocery store.” It was “such a joke,” he says. Despite choosing cremation and trying to get the most bare-bones option possible, the funeral ended up costing around $11,000.

At the same time, Mark and his wife realized there was, somewhat awkwardly, a generational split to contend with. “It was my grandfather-in-law and the older generation that wanted the open casket,” Mark says. In deference to them, they had a visitation with an open casket ahead of the cremation, further increasing costs.

Still, Mark and his wife vowed something to each other afterwards: they would try to avoid giving money to a funeral home ever again. When the next death arrived, whenever that was, they could rent an event hall themselves and get a simple cremation. Mark estimated that he could save 75 percent of the cost and a lot of stress. And the event would be nicer that way anyway, they agreed.

After all, they wouldn’t be ashamed to do a funeral on the cheap, they told each other—it was everyone else who had a problem with it.

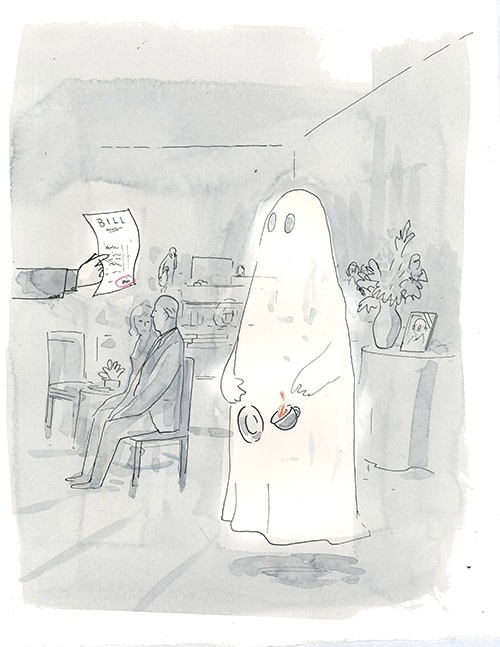

Penny-pinching millennials are blamed every day for the death of another industry, and at first glance, the funeral business seems to be one of them—killing funerals seems like child’s play in a packed schedule of ruining Hooters and not buying diamonds. While it’s true that traditional funerals are losing popularity, the explanation is a little more complicated than that; you can’t pin this one on the youth and their low-income ways—not entirely.

Remember, first, that despite the term “traditional funeral,” the funeral industry as it exists today is still relatively young. If you had died two hundred years ago, you’d likely be cleaned by your family, laid down in their parlour for a viewing, and buried in a simple casket made by your town’s cabinet-maker or carpenter.

As recently as ninety years ago, funerals like this were still common in rural communities on Cape Breton Island, for example, in my home province of Nova Scotia.

We have Abraham Lincoln to thank for birthing the North American funeral industry as we know it—or rather, we have his death to thank. The American Civil War had popularized embalming, since soldiers needed to make long journeys back to their final resting place, but Lincoln’s own embalming put the technology at the forefront of everyone’s minds. His body was taken on a two-week tour from D.C. to Illinois, with the public coming out to pay their respects and see his incredibly lifelike appearance.

Always the trendsetter (that hat! That beard!), Lincoln made embalming the hip new thing that everybody wanted for their corpse. Many other factors came into play (parlour rooms in homes had shrunk and became our modern living rooms—was the pun intended?), but one fact became clear: most families did not have the expertise or facilities to embalm in the home. Death became a job for professionals. And the funeral industry grew and gave consumers more and costlier options, until those options were the norm.

But there has always been resistance to the Cadillac Package funeral, and for those not paying attention, there were signs of a culture shift before now. One was the astronomical rise of cremations. In the 1960s, less than 6 percent of people were cremated. As of 2017, that number had risen to 70 percent. The Cremation Association of North America projects that by 2022, it’ll be 75 percent.

Still, is it all about saving cash? Eric Vandermeersch spent a decade working at a traditional funeral home in Ontario and noticed an increasing number of people calling in to price-shop in a way he wasn’t used to. They “didn’t want to spend a lot of money,” he says, but that wasn’t all: “They didn’t want a lot of services.”

Vandermeersch thinks there is indeed a cultural shift happening. But it’s among a much broader group of consumers—anybody that’s paying for funerals today, which includes many from Generation X and older. By the time millennials are paying for funerals in significant numbers (a “very, very busy” time is coming up, he says), low-cost will be the norm. And while a lot of it does come down to the Boomers’ children being more broke than they were, younger generations are also less motivated for other reasons to host a huge memorial, he says.

Older people tend to see two occasions—weddings and funerals—as “when you see everybody,” he says. These days, that’s no longer true; you don’t even have to talk to people faceto-face to know what’s happening in their lives. “If you’re plugged into the network and you’re a millennial, you sort of keep up with people without really physically keeping up with them,” says Vandermeersch, “and I think that’s really the difference.”

Religion, or a lack of it, may also factor into the shift. The Catholic Church banned cremation for centuries before deciding in 1963 to allow it for “sanitary, economic or social” reasons, and with certain conditions (including that the decision to cremate wasn’t made with “hatred of the Catholic religion” in mind). Cremation became so popular that the Vatican had to clarify in 2016 that it still discourages the option, and that Catholics are certainly not allowed to scatter the ashes or keep them at home. But there’s no putting that genie back in the urn, and with religion in general on the decline—in 2011, nearly a quarter of Canadians reported to Statistics Canada that they had no religion—those rules matter less and less, anyway.

Vandermeersch felt the tide turning nine years ago and founded his own company. Calling it Basic Funerals, he offered some stiff competition in the form of à la carte funeral services. Cremations start at $1,090 and funerals at $4,000—prices that are less than half the national averages for those services, according to a 2017 study of Canadian funerals conducted by Everest, a funeral-planning company in Texas.

Many other discount funeral companies and organizations have cropped up across Canada with names like Simple Choice Cremations, 1-800-Cremation, A Simple Cremation, and A Basic Service. There’s also DFS Memorials, a network of low-cost, independent funeral providers across the US and Canada. On its blog, powered by WordPress, it reassures customers that there’s nothing wrong with sticking to a budget: “We find the best cremation prices—so you don’t have to!”

Evangelina Coleman lost her mother last year and ended up going with a cremation at Basic Funerals, Vandermeersch’s business. Before making her final decision, she and her father went to other funeral homes near their home in Ontario and found their tendency to upsell “just yucky.” But to Coleman’s family, traditional funerals already had a number of strikes against them, expenses aside. They were so long, but, ironically, in that ocean of time, it felt like “you can’t focus on your feelings and kind of heal.”

Having seen her father-in-law go through the stress of planning a funeral for his own father, she didn’t want to prolong the pain of losing her mother. So she and a few family members simply scattered her mother’s ashes near a park where her parents often went.

Michelle Clarke, a professor in the funeral services education program at Humber College, says social media can be a double-edged sword when it comes to processing death. Nobody is more passionate than Clarke when it comes to death rites; she decided at age six to become a funeral director, making floral arrangements in her bedroom, to her parents’ confusion, and she headed for funeral school straight out of college. She watches public tragedies like the Humboldt Broncos bus crash last spring and has mixed feelings, she says; the internet is “exceptional for forcing people to be cognizant of death in our surroundings and to celebrate loss.” But it can also be “wildly detrimental when it’s used inappropriately.”

An example of inappropriate use: close friends of the bereaved will leave their condolences on a Facebook page and consider their work done. In some ways, Clarke believes this sort of behaviour contributes to a death-denying culture. Sometimes the very first person to have a face-to-face conversation with the grieving person is a funeral director, she says. That, in turn, has made it more important than ever for funeral home staff to focus on “the human side,” Clarke says.

All of this has brought up an essential question that we just haven’t given much thought to, en masse, at least not for a couple of centuries: “What is it,” Clarke asks, rhetorically, “that grieving people actually need?”

Clarke says she sometimes hear people saying they don’t want anyone crying at their funerals, and it disturbs her. “They think that ‘If I don’t have to go to the cemetery, I won’t have to grieve, so we’ll just do it this way and then nobody will cry.’ And what they’re not thinking about is, your family is still gonna cry, whether you were cremated, buried, whatever you were choosing to have,” she says. “It just means the tears happen in isolation.”

Ian MacDonald is an independent funeral planner in Halifax. Funeral planners are a relatively new concept in North America, MacDonald says. He works directly for families, helping them plan ceremonies and sift through all the options. He likens himself to a home inspector or mechanic; as an independent party, he can help people avoid emotional overspending and ensure all possibilities—not just the most expensive ones—are explored. But he does worry that in the pursuit of lower prices, something meaningful is being lost.

“People find ashes under beds, in closets, all over the place, and then they’re left with what to do with it,” says MacDonald. “How do you deal with grief? The whole idea of the funeral tradition is to help us move forward.” He says a man once told him that after picking up his father’s ashes from a funeral home, he found himself in the parking lot wondering, “‘What do I do with these? Do I put dad in the front seat, or in the trunk?’” Rather than having prepared for the emotional impact of his decision, he was “standing there outside, by the car,” MacDonald recalls, “alone.”

There is a middle ground between the generations, Clarke says. People these days are interested, more than spending a lot of money on material things, in spending on experiences—trips or concerts, for example, or live sports. Clarke teaches her students at Humber to make funerals about the experience, to create meaningful openings for catharsis. It can make people think differently about whether funerals are worth the money, especially compared to other types of spending, she says. “Look at what people are spending to go to a Leafs game right now—I’m going to drop $500 on two hours?” she says. “The long-term impact of going to a playoffs game is not the equivalent of the long-term impact of a really brilliant funeral.”

The wording sounds odd, considering the context, but Clarke has a mental list of funerals that she does consider “brilliant.” She remembers a man attending his wife’s funeral. “They ended the funeral service with him dancing with his adult daughter to the song that he and his wife danced to at their wedding.” It’s moments like these, Clarke says, that leave people crying, but also feeling reassured that things are going to be okay. If people heard that story, they would probably say, “‘Wow, that must have been really challenging for him,’” she says. “But the opposite would be true, right? Like, he would be remembering his wedding day.” The happy memory, and the reminder that he still has loving children, would be “an amazing opportunity to start healing.”

She remembers another instance where a mother died, leaving behind two children, and the funeral home decorated the room like a big garden and allowed the children to spend about a half-hour there, playing and saying goodbye to their mother. Or another time, when a child died before getting to ride the school bus, and the funeral home arranged for a school bus to be used instead of a hearse.

Funerals and remembrances don’t have to be expensive or elaborate to be meaningful, says Clarke. They don’t even need to be arranged by a funeral home. But the bereaved do need to plan something—something with meaning. And funeral homes need to be more open and inviting in order to show the true value of what they can offer. Like any other business, someone might walk in off the street simply to browse, she imagines. Or funeral homes could become more involved in the community; some have offered space for church groups to have lunches, for example. “We need to start talking about what we do,” she says.

Vandermeersch’s customers at Basic Funerals seem happy, by the metrics of our era, giving nearly universal five-star reviews on Facebook, Google and Yelp. Evangelina Coleman wrote one such review. A simple cremation followed by scattering her mother’s ashes in a park was the perfect thing to do, Coleman says. “It was really meaningful to us because... the location was special.” The simplicity made it easier to just focus on remembering and grieving.

In the end, there can be an irony to the mortification of the Gen-X or Millennial child, seemingly failing to hold proper death rites for an older relative. Sometimes, the deceased wanted that option: Coleman’s mother, for example, had asked her to spend less. “My mom and my dad had spoken about it,” at least a few times, she says. “They didn’t want anything fancy; they didn’t want to be a burden.” She says she has no regrets.

Mark says that was also partly what rankled when he got the $11,000 funeral bill. His father-in-law used to wryly say, “Just throw me off a mountain or drop me in the ocean,” Mark recalls. He was “as frugal as they come.” But Mark learned that funerals are ultimately for the living. It would be difficult to go as cheap as he wants the next time, he says, unless everyone was on board. The real accounting will be figuring out exactly what it costs to make everyone happy. “For me, it seemed like a waste of money, but I’m not everybody,” he says. “I can’t really put a price on what other people need to find closure.”