No Man Lands

Lizzie Chatham explores fictional worlds where women reign.

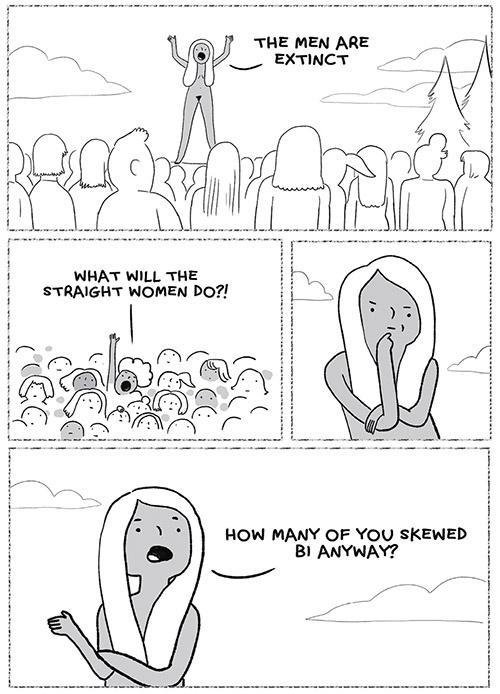

Aminder Dhaliwal sketched four words next to a drawing in March 2017, then posted it on Instagram. “THE MEN ARE EXTINCT,” she wrote. The illustration showed a naked woman, plainly a leader, standing tall on a podium and addressing an all-female crowd. It was International Women’s Day, and Dhaliwal, a Canadian artist, was announcing a new comic series. It was a dramatic way to reveal the news. Still, she wasn’t expecting the reaction.

“People assumed that the women had killed the men,” says Dhaliwal. “That was a crazy assumption,” she says, “to assume that line came from murder and bloodshed.”

To some, surely, that backlash feels less absurd by the day. For example, when a woman who credibly accuses a man of sexual assault receives death threats, while that man is rewarded with a confirmation to the United States Supreme Court, maybe it’s not so hard to imagine that women have finally sought their bloody revenge. It can even be cathartic.

When Dhaliwal’s finished graphic novel arrived this fall, however, it was clear that her imagination had led elsewhere. In Woman World—the author’s debut—it turns out that the men have simply died off from a birth defect. The remaining all-women village (appropriately called “Beyoncé’s Thighs”) looks strikingly similar to the world that women inhabit today. There are still pregnancies and periods, monogamy and the emotional blows of breakups, carpenters who build hospitals, and doctors who diagnose anxiety. But the fact that men are gone creates one significant difference: women have the power.

Fictional worlds like this—ones where women are suddenly on top—are becoming a trend of their own. Earlier this year, director Éléonore Pourriat released her first feature film, I’m Not An Easy Man, portraying a version of France where men’s and women’s social roles are reversed. And one of the biggest runaway hits of the literary world this year took this power flip a step further. In her novel The Power, Naomi Alderman imagines a world where women have developed a biological ability to release jolts of electricity from their fingers, while men have not. It slowly dawns on them what that means.

Feminist science fiction has been around for decades, but this current mini-genre offers something new, and not just because it’s finally given up niche status for mainstream popularity. Rather than inventing new worlds from scratch, these alternate universes feel very familiar—except for one thing. With their single-minded focus, however, they reveal something more mind-stretching than any sci-fi and more unsettling than any dystopia.

It is The Power that conforms most to the sci-fi label, offering a detailed premise for the world’s transformation. “Something’s happening,” Alderman writes of one character’s awakening. “The blood is pounding in her ears. A prickling feeling is spreading along her back, over her shoulders, along her collarbone. It’s saying: you can do it.” And she holds out her fingers and zaps a man from a distance. Practically speaking, when women have the ability to electrocute people at will, it makes them the more physically powerful gender—men’s greater muscular strength counts for nearly nothing.

With this small change to human DNA, everything is upended. First, girls use their electrical powers to escape from dangerous situations, and then to gain control of businesses, even religions—all the things they were seen as too weak to be entrusted with. Suddenly, boys are “dressing as girls to seem more powerful.”

I’m Not an Easy Man is more of a straight satire, going quickly to its alternate universe. Its protagonist, Damien, is a narcissistic man who is so busy catcalling two barely legal girls one day that he accidentally walks into a pole. Knocking his head, he wakes up in a different dimension, which also closely resembles today’s society—except that men are playing the roles that women traditionally occupy, and vice-versa.

Streets and buildings are named after women, and billboards show pouting, submissive men. Damien and his male friends are expected to wear whatever women tell them to, from mini-skirts to burkas. His buddies eat only salad and they nag Damien about getting married. Meanwhile, Damien is hopelessly in love with someone named Alexandra, who is strong and assertive, often dismissing his emotions with offhand declarations like “spare me the masculinist babble!”

It was through Alexandra’s character that I felt what others might have felt with Dhaliwal’s first Instagram post: catharsis. Something as simple as watching Alexandra walk away from casual hook-ups unscathed is liberating; she has never known condemnation for sleeping around. Other overt clichés usually reserved for women become so ridiculous that it’s hard not to laugh. Take one scene where Damien walks down the main street wearing sweatpants with “HOT” plastered in neon pink lettering on the rear.

But my laughter turned into an increasingly uncomfortable recognition of the violence and exploitation that runs through the film, always threatened and at times manifest. In one scene, Damien’s female boss suggests oral sex in exchange for a promotion, only to give away his projects to women and then to gaslight and eventually fire Damien when he protests. This particular scene stayed with me for weeks, not because of the abuse, but for how strange it was to see a woman violently exploit power—and for the man to be the victim. The absurdity of seeing Damien treated this way forced me to understand, in a way I usually don’t, just how normal it is to see a woman treated similarly.

The women of The Power, after a few years, are also subjecting the weaker gender—men—to devastating cruelties. They rape them, force genital mutilation on them, humiliate and torture them. What it means to be a woman changes, but the architecture of power remains the same. Take one character, Margot Cleary, the mayor of an American city, who quite literally shocks the male governor during a televised debate. Despite her fear that the momentary loss of control has cost her the election, the incident actually increases her popularity. Margot is soon elected as the new governor and recognizes that “the power to hurt is a kind of wealth.” Sound familiar?

Alderman’s novel confuses genres, with critics describing it as, at various times, science fiction, speculative fiction, satire, dystopia and even utopia. Of course, it’s hard to blame them for the confusion. After all, a universe where women control men could feel like a dystopia to some people—namely, to men. To women, that same world could look like a utopia.

Novelist Ursula K. Le Guin once said in an interview that “getting slapped with the sci-fi label” was a “kiss of death,” at least when it came to the predominantly male critics of her time. Le Guin, along with novelists like Marge Piercy, Margaret Atwood, Joanna Russ, and Octavia Butler, are now seen as pioneers for a genre that emerged alongside feminist movements in the sixties and seventies. They introduced “soft” sci-fi that explored anthropological and sociological realities, not just “hard” science. Over time that wave (of sci-fi and of feminism) retracted, until now, when many of the same conversations about women’s rights are crashing down again. But those labels are no longer a kiss of death, and the women writing in this genre are seeing more immediate success; Alderman’s novel won the prestigious Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, Dhaliwal has nearly 150,000 followers on Instagram, and Pourriat’s film is streamed internationally on Netflix.

The reason for their success is, in a single word, “Trump,” says Nicolas Longtin-Martel, a Montreal feminist scholar whose recent project involves reprinting the work of French sci-fi novelist Françoise d’Eaubonne. Longtin-Martel believes people are embracing the narrative precisely because women feel their hold on power slipping further away. Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court—and the possibility that he could go on to help overturn American women’s right to abortion—demonstrates just how quickly power can be revoked.

Still, there are other things at play; it is an odd moment for women, with fears growing just as the volume of their voices is also rising. Starting last October, millions of survivors used social media to share stories of abuse under the hashtag #MeToo. The unspoken assumption that powerful men are protected by their own set of rules seemed to begin to unravel. It was, in fact, one very public outcry against Trump’s inauguration that first inspired Dhaliwal’s comic, she says: the 2017 women’s march on Washington and others like it around the world. Dhaliwal attended the one in LA. “At that time, post-election, there was a lot of hatred,” the animator said in an interview. “It was a tense time. It was hard to turn on the TV.” At the women’s march, however, there was a “sense of community and joy and comfort,” she said, and she “walked away feeling excited.”

Social media and an increasing number of female editors have changed who gets to play critic, says Claire Saint-Esprit, an artist who works at L’Euguélionne, Montreal’s only feminist bookstore. That, in turn, has contributed to the popularity of these new works of feminist fiction. But while the sci-fi movements from the sixties and seventies were marked by a sense of progress and change, today’s seem steeped in frustration that women are continuing to fight for those same rights. It makes sense, then, that these newer works can sometimes feel less creative and less progressive than their predecessors. They only put women in power, without imagining much else.

But this zeroing-in works, just in a different way. As I read The Power and watched I’m Not an Easy Man, my own gender biases often prevented me from fully buying what was being depicted. The socially programmed part of me couldn’t help but think, for example, that women wouldn’t really execute their power so violently. If given the opportunity to rule a universe, we would of course be more compassionate and humane.

Critic Laurie Penny notes that writing feminist dystopias and utopias is particularly difficult because of just how hard it is to step outside of our own conditioning. It’s hard, she writes, “to think clearly about a better world when you’re trying to protect your soft parts from heavy boots.” Ultimately, these books and movies bring relief, most of all—the relief of seeing a rare representation of the world that women live in, that we ourselves are often blind to.

What would a matriarchal society really look like for us—how would we transform economics, city planning, community structures? It’s hard to picture it. Perhaps power-flip fiction is the necessary first step. We need to understand the world we live in before we can imagine a new one.