Families gather at a camp on Etthen Island near Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve in the East Arm of Tu Nedhé (Great Slave Lake), NWT.

Families gather at a camp on Etthen Island near Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve in the East Arm of Tu Nedhé (Great Slave Lake), NWT.

Here is Where We Shall Stay

In the Northwest Territories, Indigenous people are moving toward meaningful self-determination by resetting the past and reclaiming their cultural practices.

On the land, on the outskirts of Yellowknife, Melaw Nakehk’o holds a caribou hide in her arms. She carries it with the care and delicacy of a piece of artwork.To Nakehk’o and the many Dene hide tanners around the Northwest Territories, this is a work of art; for weeks the hide is scraped of its fur, stretched and soaked and scraped again, until it is smoked over a fire to give it a golden colour that compliments the dark green forest behind her.

“Tanning hides is a foundational Indigenous art form. It was [used for] our homes, our transportation, our clothes and, in hard times, our sustenance. It is the canvas of our visual cultural identity,” she says.“The smoke smell triggers memories of grandmothers, the sound of scraping reminds us of our aunties working together, and the beadwork and style of our moccasins represent our nations.”

The Northwest Territories is Indigenous land. Here, roughly half of the total population is of Dene, Gwich’in, Métis, Chipewyan or Inuvialuit descent. Still, the symbols of colonialism are everywhere. Walking through villages like Łutsel K’e, Fort Simpson and Behchokǫ̀ reveals stark reminders of more than one hundred years of colonization by white settlers from the south who came to extract resources from the land and spread Christianity. Churches with tall, wooden steeples are the largest buildings, and Canadian flags wave in the cool wind outside of government offices.

For generations, Indigenous people in Canada have lived under the laws and values of European settlers through forced assimilation. The Indian Residential School system, established by the federal government and instituted by the Catholic and Anglican Church, pulled Indigenous children away from their lands, families, languages and identities. The goal, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, was to bring “civilization to savage people who could never civilize themselves.”

Disease, abuse and death were realities in these schools. The recent acknowledgment of unmarked graves in Kamloops, Marieval, Kuper Island and elsewhere is proof of the systematic eradication of Indigenous people and their culture. In the community of Fort Providence, Northwest Territories, the Deh Gah Got’ı̨ę First Nation is planning to locate unmarked graves near the Sacred Heart Residential School, which closed in 1960. The church ploughed over the first cemetery, established in 1868 at the site of the original Roman Catholic mission, and turned it into a potato field in1948. Today, a memorial recognizing the dead stands as a reminder of this tragic history.

But in these same communities, residents are quietly reclaiming their connection to their heritage. In backyards, fish and meat is smoked in teepees. Children listen to Dene language classes in their schools, and Elders teach youth how to hunt and be stewards of their homelands. This is resistance to oppression. This project focuses on how Dene people in the Northwest Territories are moving toward meaningful self-determination by resetting the past. The act of reclaiming culture and identity is ongoing, and my friends here are resilient in a place where symbols and systems of colonization loom large.

We can hear colonization when Dene families pray to the Virgin Mary, but we see Indigenization when a young woman holds the hide of a caribou in her arms. In Catholicism we are Children of God, but in the Dene worldview we are One with the Land. There is a complex tension between the way of the church and the way of the ancestors. While it may be impossible to break free of the colonizers, the subtle, defiant and beautiful acts of resistance give strength to say “we are still here; here is where we shall stay.”

The title of this project is from the final story of The Book of Dene, a collection of parables from various Indigenous groups in Northern Canada. In the legend “The Two Brothers,” two boys sneak away in a canoe and get lost. They travel west, south and east, visiting many different lands and suffering tremendous hardships. Some of the people they meet ridicule and take advantage of them. After many years, they make their way to the North and are welcomed, fed and clothed by the people there. One brother says to the other,“Here is where we shall stay.” An elderly couple asks who they are and the brothers tell them about their incredible journey. It is revealed that these are the boys’ parents, and they are finally reunited as a family on their homeland.

The flag of the Tłı̨chǫ Government flies at the main camp as the season’s first snow falls. The teepees on the flag represent the four Tłı̨chǫ communities of Behchokǫ̀, Whatìi, Gamètì and Wekweètì. The sun and water symbolize a 1921 quote by Chief Monfwi: “As long as the sun rises, the river flows and the land does not move, we will not be restricted from our way of life.”

Drummers sing while Louis Zoe feeds the fire with an offering of bread and tobacco, a way to ask The Creator for safe travel and offer thanks before the day begins.

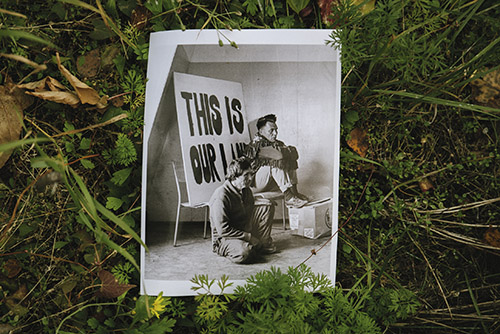

A photo of two men sitting beside a sign that reads “This is our land” during hearings of the 1974 Berger Inquiry. The discussions between Dene communities and Justice Thomas Berger assessed whether a pipeline stretching from the Arctic Ocean to Alberta would affect communities in the NWT. Berger ruled it would violate treaty rights and impact the culture and health of Indigenous communities.

Sage burns in a smudging bowl on Lila Fraser Erasmus’s dining room table. “Our traditional medicines have strong healing powers—sage, spruce tips, chaga, fireweed, rat root—all of these plants we find on the land can help us with common sicknesses [and] serious diseases. If you take something from the land, it has to be picked with good intentions or else it won’t work. This is a very spiritual process for us.”

An Anglican Church archival photo of three Dene girls near present day Behchokǫ̀, NWT.

Melaw Nakehk’o is a moosehide tanner, artist, filmmaker and mother. “Hide tanning is a revolutionary act of resistance,” she says. “We occupy our traditional land, we are adhering to our traditional teachings and honouring our relationship with the animals that sustain us. Moosehide tanning is Land Back.”

Shene Catholique-Valpy has given her daughters Sahᾴí̜ʔᾳ and Náʔël Nóríyá traditional Denesołįne names. “In residential school...they only gave [children] numbers to be called by. By reclaiming names, I am showing that we are still here.”

Gail Cyr and Besha Blondin are respected Elders in Somba K’e (Yellowknife). Here, they stand together after a ceremony recognizing missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the NWT.

Ribbons tied to a Tree of Honour pay tribute to the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the NWT. In 2019, a federal inquiry found that Indigenous women and girls were twelve times more likely to be murdered or to go missing than members of any other demographic in Canada—and sixteen times more likely to be killed or disappear than white women.

Khloe Cardinal walks among a group of friends and family gathered on a small island to honour the memory of Sam Boucher, Cammy Boucher and Jake Gully, who drowned while travelling to Łutsël K’é over thin ice on their snowmobiles in 2019. The gathering is not only a way to show respect, but to recognize the spiritual return to the land.

Chase Lockhart makes an offering of tobacco near the community of Łutsël K’é, a way to show respect to the water and pray for safe travels upon it.

The aurora borealis appears over the community of Dettah, NWT.

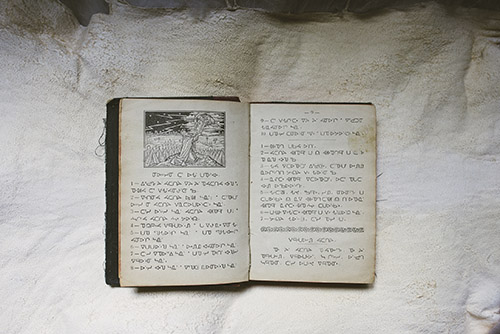

The bible of Victor Mercredi, a Métis man who lived in Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, was given to him by an Oblate in 1924. The bible was often written in syllabics—a way for settlers to translate Indigenous languages into written words. Missionaries distributed the bible to Indigenous people as they established churches and formal communities throughout Canada.

After thirty-nine years as a couple, John Doctor, sixty-five, and Pauline Zoe, fifty-eight, get married in St. Michael’s Catholic Church in the Tłı̨chǫ community of Behchokǫ̀. Doctor recently retired from the Rio Tinto-owned Diavik Diamond Mine, one of three diamond mines operating in the NWT. “We have a family, but I figured it was time to make it official. I’m glad she said yes.”

An abandoned shrine near Somba K’e (Yellowknife) close to the Trapper’s Lake Spirituality Centre. While mostly a place where teenagers come to party, people still leave offerings and prayers.

This project was created for the World Press Photo 2020 Joop Swart Masterclass.

Pat Kane is a photographer in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. He takes a documentary approach to stories about people, life and the environment in Northern Canada. His work focuses on Indigenous issues, and the relationship between land and identity. Kane is a grantee of the National Geographic Society’s Covid-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists, and an alumnus of the World Press Photo Joop SwartMasterclass. He’s a member of the photo collectives Indigenous Photograph and Boreal Collective. Kane is also the co-founder and president of the Far North Photo Festival, a platform to help elevate the work of visual storytellers across the Arctic. He acts as a mentor with Room Up Front, a program for emerging BIPOC Canadian photojournalists. Kane identifies as mixed Indigenous/settler, and is a proud Algonquin Anishinaabe member of the Timiskaming First Nation (Quebec).