Illustration by Jay Dart

Illustration by Jay Dart

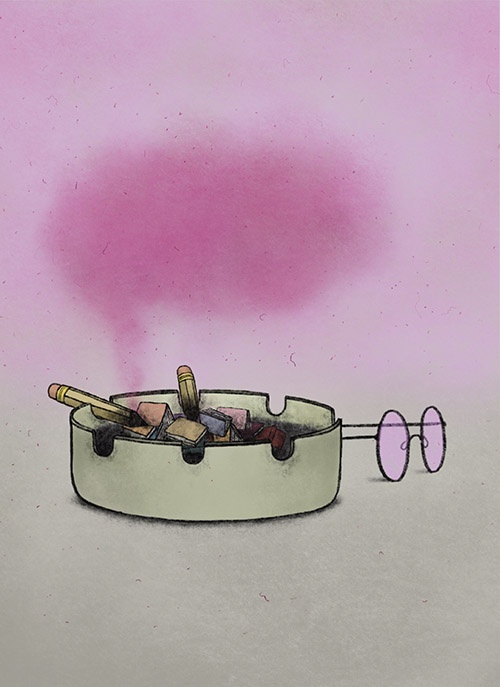

Blowing Smoke

Is Canadian literary criticism on its last breath? Emily M. Keeler assesses.

For the past six years I’ve been trying, with varying levels of success, to quit smoking. I’ve managed to stop buying cigarettes, but every smoker I know will tell you that if you light one up, I’ll appear at your side with a pleading look in my eyes. For the most part, I buy disgusting white plastic-tipped cigarillos, one or two per day. They are shameful, stinky things but so far I can’t quite give them up.

In a 1946 column in the Tribune, famous smoker George Orwell tallied up the total investment represented by his nearly five hundred volume personal library. He found he spent more per annum on Player’s tobacco than he did on books. Adjusted for inflation, his pack-a-day habit cost him £1,782, or $3,038 Canadian. As for books, he estimated a cost of £25 per year in his time and currency, an amount that would be in the neighbourhood of $1,899 in ours. My cigarillos are $2.50 a pop and I will absolutely not be doing the math on that.

For Orwell, putting the cost of smoking up against the cost of reading was salient because he—a writer and reader of essays, novels, journalism and book reviews—believed that the chief issue with literature in his day was that the general English reading public didn’t want to spend their money on books. Well, perhaps not the chief issue, but one pressing enough for him to write a newspaper column about. For my parochial Canadian purposes, pitting literature against smoking in a competition of the best use of one’s limited leisure fund is admittedly less salient.

Last year, 94 percent of Canadians spent money on books. BookNet Canada, the country’s best source of national publishing data, found that 15 percent of us spent an Orwellian $100 or more per month. In 2021, we collectively bought over 52 million books. Suffice to say, for my purposes, it might be better to align the increasingly unpopular tobacco habit with the all but disappeared landscape of Canadian book criticism.

Let’s come back from across the pond and look first below the 49th parallel. In August last year, the extremely Brooklyn-based literary journal n+1 ran an unsigned editorial on the abysmal, debased status of the contemporary book review. The general book-buying public, the editorial editorialized, is tired of hearing about only Rachel Cusk or Sally Rooney, is tired of longish themed essays that touch on new books by putting them in conversation with books by Sally Rooney or Rachel Cusk. The reading public, they went on, is being lied to in blurbs and reviews alike, as underemployed careerists and hungry grad students do freelance book criticism to curry scraps of favour in an increasingly fragmentary media and publishing ecosystem of tweets and Slack channels and bylines and book deals:

The main problem with the book review today is not that its practitioners live in New York, as some contend. It is not that the critics are in cahoots with the authors under review, embroiled in a shadow economy of social obligation and quid pro quo favor trading. The problem is not that book reviews are too mean or too nice, too long or too short, though they may be those things, too. The main problem is that the contemporary American book review is first and foremost an audition — for another job, another opportunity, another day in the content mine, hopefully with better lighting and tools, but at the very least with better pay. What kind of job or opportunity for the reviewer depends on her ambitions.

There are, n+1 contends, too few staff critics, and freelancers are paid too little money. There is a lack of consideration and curiosity, there are only wheels to be greased, spinning ever faster. As you might expect, the salvo lit up the neurons of the online republic of readers and writers, fuelling a few good hours of discussion about the role of the critic today, the problems with book reviewers and publishing, and of course the issues of kept gates and coastal elitisms. My contribution to the online discourse, looking back on a decade’s worth of bookish gigs as a reviewer and editor out on the Canadian book-and-media tundra, could be condensed into a single tweet: lol, it’s even bleaker in Canada.

And indeed, it is. The Globe and Mail, which once had its own dedicated pull-out print section for book reviews on Saturdays, now runs on average a single review per week. (One recent selection for coverage in the sole review spot: the $64.00, 800-page George III: The Life and Reign of Britain’s Most Misunderstood Monarch, a book that absolutely everyone is talking about and that surely most Canadians have special ordered in from Random House UK, as it has no Canadian publisher.) Sometimes the review is actually an interview, often with an American journalist, or a three-book roundup of mostly nonfiction books with a timely plug. The Toronto Star runs a few short book reviews each weekend, with the occasional longer review or author profile. The National Post no longer has a books section, though it did once—section editors emeriti include Jessica Johnson, who now edits the Walrus, Mark Medley, the deputy editor of the Globe’s Opinion section, and yours truly, whose tenure there coincided with a pack-a-day smoking habit.

That’s just the newspapers, of course. Maclean’s has dedicated books coverage, though not necessarily reviews so much as profiles and themed lists, in each issue. There are a handful of smaller circulation magazines with a focus on reviewing books in this country, like the Literary Review of Canada, Quill & Quire, and Canadian Notes & Queries, but they tend toward, shall we say, niche readerships and small contributor’s fees. What kind of careerist, then, could possibly make a go of reviewing books in Canada?

In another Tribune column from 1946, “Confessions of a Book Reviewer,” Orwell depicted the humble work of book criticism as harried and dirty, taking place primarily in “a cold but stuffy bed-sitting room littered with cigarette ends and half-empty cups of tea.” The column was more than a touch parodic, but it’s useful to think of how his jest that a “regular reviewer” would analyze around one hundred books per year necessitated a culture where many, many more than one hundred book reviews were published per year.

Obviously, for there to be that many book reviews there would also have to be more newspapers and magazines. When I joined the National Post in 2014, I was informed that my editorial direction over the paper’s book section would determine coverage not only in the paper whose logo emblazoned my business card but in most of the regional Postmedia properties, like the Ottawa Citizen, Calgary Herald, Vancouver Sun and Winnipeg Sun, for instance. I remember my new boss telling me I would be not only the book editor of the National Post, but essentially the national book editor.

The power I held through media consolidation merely meant that the same review of, for example, Sean Michaels’s 2014 Giller-winning novel, Us Conductors, would run in a dozen papers, whereas previously individual news rooms would assign their own critics, with diverse regional perspectives that were, ideally, tied to their readerships. It’s hard to feel the buzz-worthiness of even a big, prize-winning book if there is but a single voice buzzing. Now, Postmedia is without a national books editor and has shuttered papers in several small markets.

Late last year, Jessica Johnson wrote a cover story for the Walrus on the bleak future of Canadian journalism. Her findings were mostly dispiriting. After interviewing many present and former media workers, Johnson found that no one has the fix. For the most part, in terms of readerships, job sustainability and news service in small and medium markets, Canadian journalism has essentially already collapsed.

People at all levels of Canadian media, from upstarts and Substackers to the outgoing editor of legacy products like the Toronto Star, told Johnson that they had little in the way of good news or solutions. “Senior media executives talked to me off the record or on background because they didn’t want their personal pessimism attached to their professional titles,” she wrote. “Everyone who had left the media altogether said they were so glad to be out of this terrible business.”

Giant conglomerates like Rogers, St. Joseph’s Media, Bell and Postmedia have bought up market share in order to make entire media properties—and their employees—redundant while C-suiters did nothing but wring their manicured hands for twenty-five years as Craigslist, Google and Facebook disrupted their business models. It is, to be frank, depressing. It is also one of the major reasons complaining about the state of book reviewing in this country feels like attending a funeral dressed as a clown.

Book reviews, it must be said, have very little utility. Listicles and elimination battles like the CBC’s Canada Reads can do a lot to make consumers—i.e., readers—aware of books that are available to purchase. In Canada, over ten thousand such purchasable titles are published per year. But for readers and writers alike, such bits of promotion don’t yield the same marvels as a healthy review culture, where it’s possible for a book to both make a splash and get dragged through the mud, to land among the public with a satisfying thud rather than airy, decentralized silence. (It’s worth noting that publishers, too, rely on review culture for the enrichment and development of literature in this country, with the juries of various funding bodies adjudicating the ability of any independent press to get its books, well, reviews.)

The pleasure of a brilliant book review doesn’t lie in its ability to promote or pan; a healthy culture of book criticism has a chiefly aerobic function, in that it strengthens the public body’s ability to circulate and evaluate ideas, to appreciate and understand the literary arts as one conduit of engagement with the vastness of the world. Without meaningful investment in Canadian media, the book review is wheezing along a shrinking track, where readers like me will still chase after them, until all that’s left is shameful, stinky smoke. ✲

Among other things, Emily M. Keeler has been an editor for Flying Books, Coach House Books and the National Post, where she assigned and edited hundreds of book reviews. She lives in Toronto, where she is currently at work on a novel about being perceived.