Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Horning In

Satirical politics is a family affair for this second-gen Rhino, but does politics still have room for humour?

“Rhino Takes Brazilian Election Victory With

Aplomb,” read the 1959 New York Times

headline. A young rhinoceros named

Cacareco (which translates to “rubbish”) had

just trampled her competitors to become the top

candidate in São Paulo's municipal elections, voted

in by residents who were frustrated with soaring

inflation, crumbling infrastructure and the ruling

government’s inability to address either. “Better to

elect a rhino than an ass,” one voter remarked in

an interview with the media.

It was a message that resonated with a certain

set of politically disenfranchised Canadian

eccentrics. Four years after Cacareco’s triumph,

she became the inspiration for a Montreal party

with the dual aim of poking fun at the political

system and entertaining the voting public. In 1963,

physician and writer Jacques Ferron founded the

Rhinoceros Party of Canada, which he described

as an “intellectual guerrilla party.” The party picked

Cornelius the First, a local rhino from Granby

Zoo, as the symbolic leader, ostensibly because

of Cornelius’s and politicians’ shared qualities of

being, as the party line went, “thick-skinned, slow-moving, dim-witted, [able to] move fast as hell

when in danger, and [having] large, hairy horns

growing out of the middle of their faces.”

Humour has always been central to the Rhino

Party. Marxist in the Groucho sense, their mission,

as stated on the party website, is to “make Canadians laugh while laughing at politicians.” Over the

years, candidates have promised to repeal the law

of gravity, nationalize Tim Hortons, count the Thousand Islands to make sure Americans haven’t stolen

any, put the national debt on Visa, turn Montreal’s

St. Catherine Street into the world’s longest bowling

alley and ensure that every Canadian experience a

monthly orgasm. If they ever win, they also promise

to immediately dissolve and force a second election.

Of course, the basic credo of the party has been “a

promise to keep none of [their] promises.”

The Rhino Party’s form of absurdism has been

a consistent presence in Canadian politics for the

past sixty years. They’ve never won a single seat, but

they did receive over one hundred thousand votes

in the 1980 election, in which a professional clown

who ran for the party placed second in Montreal’s

Laurier riding, beating out the New Democrat and

Progressive Conservative candidates. In 1984, they received the fourth-largest number of votes in the

country, beating out all but the three major federal

parties. More recently, in 2019, they even managed

to steal a few votes away from People’s Party of

Canada leader Maxime Bernier, by running another

candidate named Maxime Bernier in his home

riding of Beauce, Quebec. Even if most Canadians

aren’t aware of the party’s full history, the Rhinos

have built a reputation for themselves as reliable

entertainers—and I was lucky enough to grow up

with a front-row ticket to the show. But in today’s

political landscape, when the system already feels

so much like a circus, is there still room for the

clowns to have their fun?

“Lawyer bears baby Rhino,” read the birth announcement, buried deep in the Sarnia Observer. It was

1991 and I had just entered the world with my

political allegiances pre-determined. Three years

prior, my father had paid $200 and gathered the

necessary twenty-five signatures in order to register as a first-time candidate for the Rhino Party in

our home riding of Sarnia–Lambton, Ontario. His

campaign t-shirt was emblazoned with the slogan

“We are not sheep,” reiterated on the back in Latin

and accompanied by an illustration of a sheep

encircled and crossed out, like a no-smoking sign.

I still have one, threadbare and yellowed with age,

that I wear every election. It reminds me of how I

looked up to him as a kid, not yet understanding

politics, just knowing that it seemed fun.

In a local news story from my father’s first campaign, the reporter scoured his life for a way to

frame him accurately: his stylish home (an artsy

progressive?), his oil refinery job (a blue-collar

hero?) and his side business selling canoes and

kayaks from our home’s garage (an enterprising

hustler?). None of it seems to square with the “outrageous” political ties implied by a Rhino Party

candidacy, and the reporter ultimately concludes

that “when speaking to Mr. Elliott, there is no sign

of radical behavior. He is not short a few bricks, his

elevator goes to the top floor, and both oars—or

at least paddles—are in the water. The bearded

bespectacled man is simply voicing his political

preference with tongue firmly planted in cheek.”

The baffled journalist was correct: if my father

was sincere about anything, it was the insincerity

that he found in mainstream politics—he never missed an opportunity to call out politicians who

toed party lines or relied on simple soundbites.

Over the years, my dad continued to run, and I

dutifully wore an election t-shirt to school during

his campaigns, clipped newspaper articles and

handed out lawn signs to our neighbours. I began

to understand the uniqueness of my father’s Rhino

affiliation, especially in our conservative town, and

how much it was shaping my own politics. The Rhino

ethos was appealing to an angst-ridden adolescent

like myself. My father’s campaign materials boasted

that he was the “revolutionary alternative” and

exhorted people to “stick it to the man.” He opposed

the local Christian Heritage candidate, supported

gay marriage and environmental protection, and

proposed a “two-beer” health-care system (because

everyone feels better after two beers). This was a

political education that made an impact, unlike

my unbearably dry high school civics class that

tried to cram the fundamentals of democracy into

a nine-week curriculum. Even if I couldn’t fully

explain it yet, I knew when I looked at my father,

bearded and disheveled as he stood alongside the

traditional candidates in group photos, that he was

offering an important alternative to the status quo.

My father’s first election was his best outcome: 1

percent (408) of the total votes in Sarnia–Lambton.

Nevertheless, he persisted. In a 2006 interview with

the Sarnia Observer, when asked why he continued

to run for office, my father explained that he was

using satire to show just how shallow the promises

and platitudes of the political parties could be.

The real power of the Rhino Party’s antics has

always been to reveal the absurdity inherent in

the political system. They didn’t create it, they just

stripped it of all pomp and circumstance and then

topped it with a clown nose for good measure. In

the 1988 party platform, their solution to the federal

deficit was to transfer it to a government social

services program “where it will be reduced through

a series of budget cuts.” From a certain perspective,

the very idea of a federal deficit is nonsense (money

is made up!). But also: social services programs

are dealing with massive budget cuts, in which

very tangibly real and necessary services disappear

through the magic of economic trickery. That’s how

the Rhinos work: strip all pretense away so that the

system is revealed for the scam that it is, and then

point out all the damage that the scam has wrought.

Eventually, the bureaucratic system got the best of

the Rhinos. The party temporarily dissolved in 1993

in protest of Bill C-114, passed by the Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing

with the aim of both increasing voter accessibility and the legitimacy of political parties. While the

bill introduced some measures that benefitted

voters—mail-in ballots, for example—it required

that each political party nominate candidates in

at least fifty ridings and that each candidate pay

$1,000 (which would be partially refunded by the

federal government only if the candidate won 15

percent or more of the vote—which the Rhino

Party never managed to get). If a party could not

pay the $50,000 total entry fee, then they would

be automatically removed from the electoral system. The Rhinos viewed these new requirements

as deeply unfair, preventing candidates who were

economically disadvantaged from participating

in the electoral process, and their refusal to fulfil

them led to the disappearance of the party from

the political sphere. The Rhinos weren’t alone in

condemning the political fallout of the bill; the

Globe and Mail called it “the worst violation of

Canadians’ right of free expression in years,” and

fourteen registered political parties contested the

election—a Canadian record.

In the years following, former Rhino candidates

kept the party’s spirit alive. François “Yo” Gourd,

a 1979 Rhino candidate, started Les Entartistes, a

faction of L’internationale des Anarcho-Patissiers

(International Pie Anarchists) whose raison d’être

was throwing cream pies in the faces of prominent

politicians. In Quebec, targets included Jean Charest and Stéphane Dion. “The federal government

has closed the door to protest parties, so people are

going to find other outlets,” explained former Rhino

candidate Charlie McKenzie. “Now it is with pies.”

My father, for his part, kept running as an independent candidate, calling himself a “Bonehead” as an

homage to his beloved party. After the contested

electoral requirements were struck down in 2004,

due to the guarantee of the right to be a candidate

outlined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and

Freedoms, the Rhinos stampeded back into the

political arena with two candidates in by-elections

in 2007 and seven in the 2008 federal election.

Today, electoral reform remains a key issue for

the party, and one that they approach with an

almost uncharacteristic solemnity. Elections in

Canada are decided by a first-past-the-post (FPTP)

voting system, in which the candidate with the

highest number of votes wins a seat in the House

of Commons to represent their riding. Under FPTP,

candidates can win seats with far less than a majority of the total votes, and the proportion of seats

won by each party doesn’t necessarily match the

proportion of the votes garnered. This leads to

election results that don’t reflect the popular vote,

including “majority” governments elected by less than 50 percent of voters—the last time a majority

federal government was elected by a majority of

voters in Canada was in 1984.

In 2022, to draw attention to the faults of FPTP,

the Rhino-affiliated “Longest Ballot Committee”

collected five thousand nomination signatures and

organized to put thirty-four Independent candidates on the ballot of the Mississauga–Lakeshore

by-election. Many of these candidates were from

outside of the riding and even outside of Ontario,

meant as a dig to sitting MPs and ministers who

live outside of their own ridings (which is permitted under the current Elections Act). “The voting

system we have right now in Canada was put in

place 250 years ago in rural UK,” the party said in

a Facebook post about the initiative. “It is not a

system that fits urban Canada now. This system is

creating apathy and frustration inside the population … This is a serious threat to our democracy.”

While overcrowding the list of candidates might

seem confusing or even distracting to some, the

action is a natural continuation of the Rhino Party’s

“chaotic good” political strategy.

“For us, elections are a game, so we play the game

with their rules, and we make fun of the rules,” explains Rhino Party leader (or, as he likes to flip the

word, their “dealer”) Sébastien CoRhino, who ran in

the Mississauga by-election despite living over one

thousand kilometres away in Rimouski, Quebec.

CoRhino, a musician and studio technician, has

been involved with the party since 2008, when he

ran as a candidate in Sherbrooke, Quebec while at

university. For the head of a political party, even a

satirical one, he’s refreshingly informal—his email

signature apologizes for any “missed steaks” or

“criminal offences under Canadian law”—and he

quickly takes any opportunity to distance himself

from the political establishment.

CoRhino runs the party with no staff, just a small

team of volunteers. He points out that sitting politicians aren’t going to change something that

keeps them in power, and recent history seems

to prove him right. Justin Trudeau’s 2015 promise

of electoral reform, intended to “make every vote

count,” struck a hopeful note with voters who had

become disillusioned with the FPTP system. In 2015,

the Liberals won a majority government with just

under 39 percent of the popular vote. By early 2017,

Trudeau had abandoned the promise of reform

entirely, ostensibly because of a lack of consensus

around an alternative.

Vote, we are told, every time we express cynicism with the current political situation. Be a

democratically engaged citizen. Make your voice

heard! But when the first-past-the-post system produces such disproportionate results, and

strategic voting often seems like the only sensible

option, it’s not surprising that the average citizen is

feeling cynical—or that voter turnout has decreased

6 percent, dropping to 63 percent, since 2015. In

comparison, data from the International Institute

for Democracy and Electoral Assistance shows that

for countries within the OECD with non-compulsory

voting, the highest voter turnout occurs under those

with a proportional representation system, with

Denmark (84.6 percent), Sweden (84.6 percent)

and New Zealand (87.2 percent) topping the list.

I was able to vote for the first time in the 2011

election, and I was thrilled at the prospect of finally

casting a ballot for the Rhino Party after years of

watching my father campaign. Still, the guilt of not

having voted strategically to oust my local rightwing MP nagged at me. Shouldn’t I have voted for

the candidate most likely to prevent a Conservative

win, even if they weren’t my candidate? Wasn’t I

just wasting my ballot, choosing a fringe candidate?

In her study of the effects of satirical content

on political participation, political scientist Erica

Petkov uses the term “productive cynicism” to

define “a sense of frustration with the political

status quo coupled with a desire to become engaged

nonetheless.” This conflict echoes the philosophy

of absurdism: the search to find meaning in a

meaningless world. While political satire has

often been relegated to shows, comedians and

commentators who sit outside of the system—the

Beaverton, Rick Mercer, This Hour Has 22 Minutes—

the Rhinos are committed to bringing their antics

directly into the arena. “Today, everyday people

remain frustrated with the archaic and out-of-touch

political system which our leaders have refused to

reform,” a recent post on the party website declares.

“Instead of accepting apathy and alienation, we

decided to do the opposite; and engaged directly

with our democracy to make ourselves heard.”

“When the dictators of tomorrow seriously promise

things that I clearly could have said as a joke, where

is my place in this discourse?” CoRhino’s question,

posed recently on his Facebook page, sums up

the challenge the party faces today. Trump, Ford,

Johnson et al have shown us the dark side of absurdity; the distinctly unfunny reality of what can

happen when a “joke” candidate is elected sincerely.

The role of political satire has historically been to

reveal the lunacy and ridiculousness of those in

power, but we no longer need comedians to drive

the point home—politicians do it well enough on

Twitter, for all to see.

Some lines from my father’s old speeches, which repeatedly call out the actions of “backroom power

brokers, party hacks and corporate elites,” feel eerily familiar in the midst of a populist wave across

global politics (never mind that today’s career politicians branding themselves as “outsiders” or “of the

people” bear little resemblance to the blue-collar

workers that filled the Rhino Party’s ranks in its

heyday). In 2000, as I entered the fourth grade, my

father argued in a campaign speech that Parliament

had become the “playground of the political parties”

who “consolidate their stranglehold on the political

process,” while the average Canadian grows more

and more cynical and alienated. Today’s populist

politicians specifically target this brand of voter

alienation, stoking anger and feeding upon fear in

order to gain control of the system that caused it in

the first place. Rather than seeing those alienated

Canadians as tools to gain power, only to be forgotten after an election and further disenfranchised by

a cruel and oppressive legislature, the Rhino Party

has, since the 1960s, welcomed those Canadians

into their ranks, giving them an alternative not

only on the ballot but in the entire political process.

“The enemy of humor is fear,” satirist Malcolm

Muggeridge wrote in a 1958 article for Esquire. “Fear

requires conformism. It draws people together

into a herd, whereas laughter separates them as

individuals ... In a conformist society, there is no

place for the jester. He strikes a discordant tone,

and therefore must be put down.” Reading this, I

remember my father’s original campaign shirt: “We

are not sheep.” The Rhinos aren’t trying to stoke

QAnon levels of paranoia or drive their members

to violent actions. They are trying to keep the “productive” part of Petkov’s productive cynicism alive,

to remind us that the system really is flawed. But,

more crucially, they remind us that there could be

another way—and that there are others out there

who believe in it.

The emails started landing in my inbox late last spring.

One, with a subject line marked “Membership!!!”,

informed me that Elections Canada had asked

the party to confirm that they have the requested

minimum of 250 members, an administrative

task required of all parties every three years. On

November 6, 2022, CoRhino sent a pleading follow-up to members to send in the necessary paperwork.

“Currently, we are up against the wall,” he urged us.

“If we do not have the requested forms within more

or less 10 days, the Rhinoceros Party of Canada will

be deregistered.”

It’s not easy being a fringe candidate. My father

ultimately stopped campaigning in part because he

couldn’t get paid time off work in order to run. In an op-ed during one of his campaigns, he pointed

out that when a local political campaign needs a

full-time staff of a dozen-plus people, it “illustrates

perfectly what is wrong with the state of Canadian

politics today.” That was in 1998. Today, CoRhino

tells me that he wishes he had more time outside

of the work of navigating electoral bureaucracy

to focus on long-term strategy. He’s planning

a “disorientation” weekend this summer, where

party members and candidates from across the

country will meet up to reevaluate their strategy,

rethink their platform and restructure their

internal organization. “We have sixty years behind

[us], but where do we want to Go?” he wrote to me

in an email, the capital-G seeming to emphasize

the expanse of opportunity—and uncertainty—

ahead of the party. He still believes that satire has

a necessary place in politics but that “we have to

be careful of how to do it,” acknowledging how

easily things can become distorted in today’s

political discourse. For the humour of the Rhino

Party to make an impact, it must confront, not just

contort, the damage wrought by the current power

structure, and that requires real time, organization

and effort. However, it should be noted that this

summer’s planning session will take place in

Quebec's Eastern Townships at ShazamFest, a

circus festival “where the misfits fit in!”. Old antics

die hard.

I write this from the house that my father built,

both figuratively and literally. His first candidate

registration form, from back in 1988, lists his address as “RR#2.” No street address, just a lot number

on a rural road in a tiny hamlet, where he had

recently finished constructing a modest two-bedroom. He was thirty-two, the age I turn this year. I

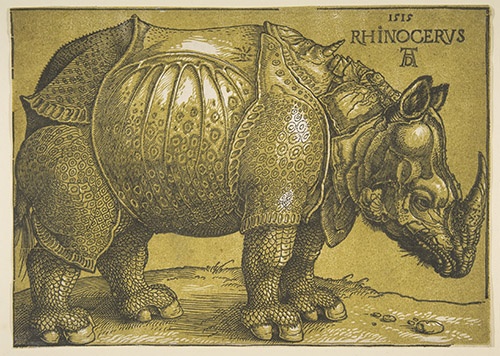

look at the framed print of Albrecht Dürer’s 1515

woodcut, The Rhinoceros, hanging on the wall, the

party’s logo and the same image I have tattooed

on my back. Nearby, I see the bookshelves stacked

with Che Guevara biographies and Far Side comics,

Shakespearean comedies and firearm manuals,

Kropotkin and Homer and No Logo and the Onion.

Would I have the interest in politics, the skepticism

for authority, or the optimism for social change

if I hadn’t been born a baby Rhino? Somehow, I

doubt it.

The party ended up receiving 260 signatures

before the November cut-off date, my own included.

The Rhinos will live—and laugh—for at least one

more election cycle, providing voters with what

my father’s merch deemed “the revolutionary

alternative.” I’ll be there with my carte membre à

vie, ready to feel the smallest flicker of optimism

as I cast my vote. ⁂

Blair Elliott is an event producer and writer based in Montreal.