Heirloom

The purchase of a loom leads to a contemplation of the fabric of identity through a legacy of Diné weaving.

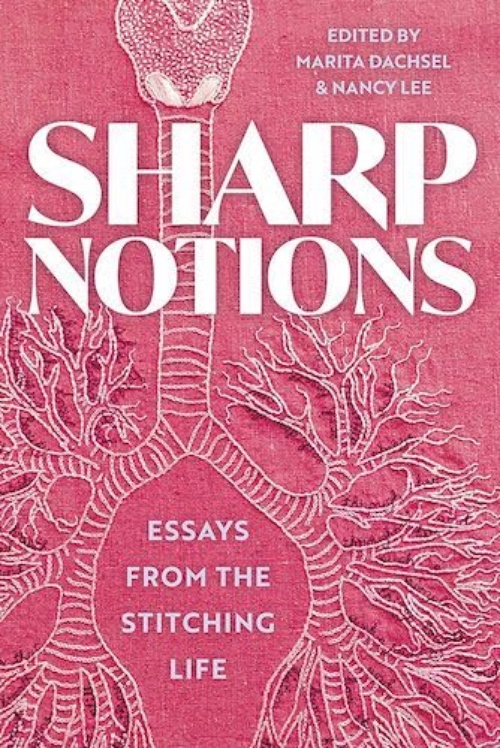

Excerpted from the essay "Heirloom" by Danielle Geller from the anthology Sharp Notions: Essays From the Stitching Life edited by Marita Dachsel and Nancy Lee (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023).

“I don’t know how the first spider in the early days of the world happened to think up this fancy idea of spinning a web, but she did, and it was clever of her, too.

—Charlotte’s Web, by E. B. White

In 2001, a nineteenth-century Navajo chief’s blanket was brought to the stage of Antiques Roadshow. The blanket’s design was simple, with thick bands of black, white and blue, but chief’s blankets were important trade items for the tribes of the plains, and then for white settlers. The yarn was hand-spun from the coarse, curly wool of Navajo-Churro sheep — a Spanish import, bred native — and the textiles were so tightly woven they were nearly waterproof. Back then, a blanket woven by a Diné (Navajo) weaver could cost a year’s wages.

The clip from the episode is still hosted on YouTube, and the blanket is called one of the show’s “Greatest Finds!”

Ted, the elderly man with the blanket, holds his hands firmly behind his back throughout the appraiser’s assessment. When the appraiser asks what he knows about the rug, he rolls his shoulders in a small shrug. “It’s probably a Navajo,” he says, “but that’s about all I know.”

“Ted, did you notice when you showed this to me that I kind of stopped breathing a little bit?” The appraiser is anxious, giddy. The blanket, he tells Ted, is a first-phase blanket, one woven for Ute chiefs. Though the blanket was likely woven between 1840 and 1860, there is little apparent damage, and though the blanket is wool, it feels like silk. The white and black stripes reflect the natural colour of the wool — if you ever find yourself close to a chief’s blanket, you can see that the black bands waver between shades of deep, dark brown—and the blue was dyed with indigo. “This is Navajo weaving in its purest form,” the appraiser claims, and then he delivers Ted the good news: on a bad day, the blanket would be worth $350,000 USD; on a good day, it could sell for around half a million.

“Gee,” Ted squeaks, pressing his hand to his chest. “I can’t believe this!” The blanket had been hanging on the back of a chair in his house. In 2016, Antiques Roadshow updated the appraisal of the blanket, increasing its maximum value to a full million. In 2021, it was updated again to a possible maximum of two million.

My mother was Diné. She was raised in Window Rock, the Navajo Nation’s capital, on the reservation. After she graduated high school, she moved with my white father to South Florida, where I was born, to escape a life of poverty, alcoholism and abuse — though the life she lived with my father was also one of poverty, alcoholism and abuse. When I was still little, my mother transferred her parental rights to my dad’s mom, with whom my sister and I moved north.

Held apart, the thread between my mother’s life and mine wore thin.

But for my college graduation, she gifted me her mother’s blanket, striped white and orange and forest green. It was the closest she ever came to sharing something from her family and her home, a people and a place she didn’t want us to know.

After she left, as I spread the blanket across my bed I noticed a blue-and-gold label in one corner that read Pendleton Woolen Mills. The discovery was a downward spiral into the commercial history of textile production and one of the great innovations of the Industrial Revolution: the power loom.

When the first-phase chief’s blanket was woven, weavers had already begun to automate textile production. The Jacquard loom, developed in the wee hours of the nineteenth century, was a machine that produced intricately designed textiles through a system of punch cards, which many historians cite as an early inspiration for modern computing. The meaning of weaver as a professional designation shifted from “person who weaves” to “person who operates machine.”

In the early history of Pendleton Mills, a Jacquard operator working for the company, Joe Rawnsley, consulted with nations throughout the Pacific Northwest to design textiles incorporating their preferred colours and motifs. One might look at this history and call it appropriation, exploitation, but Pendleton Mills attained a status of cultural significance. Because handwoven Navajo blankets and rugs are so costly in time and skill, because Navajo textiles hold significant commercial value, most Diné families can’t afford them, and Pendleton blankets are gifted at graduations and weddings instead.

I wasn’t familiar with this history until I began digging around the internet that night. And even though I discovered the Pendleton blanket had become a traditional gift, that tradition had shifted shape, I found it hard not to feel disappointed. It was as if my relationship with my mother could be defined only by loss — of family, of tradition, of knowing, of memory.

After my mother died, there were many things I resigned myself to never knowing. I would never know the Navajo language, which she hardly knew. I would never know her parents, my grandparents, who had already died. I would never know her favourite colour, her favourite song, her first kiss. I would never know how to see her home through her eyes. So I looked around for something I could know and decided I would learn how to weave.

I learned to weave from Jennie Slick, whose mother was a friend of my great-grandmother, herself a woman who weaved. I learned from Lori Begay, who taught me that weaving is a kind of inheritance. “It was given to you,” she told me, as if weaving were embodied knowledge, as if my hands and my heart were born for weaving, just as a spider is born with the art of the web.

I learned to weave in an old trading post. In the conference room of a Quality Inn. In a room at the Heard Museum, an institution dedicated to American Indian art, that was full of Diné women, young and old. I learned to weave in silence and in laughter and in the beauty betwixt and between.

Most recently, I learned to weave from Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete, two master weavers of Two Grey Hills. In K’é, the Diné kinship system, I am related to them by clan. In their class, they gave equal weight to story and craft, and as we wove, they shared family stories and origin stories, some of which they published in their book, Spider Woman’s Children. “At its core,” Barbara writes, “K’é is knowing where you come from, learning language, culture, prayer, songs, and your origin stories.”

In one of our origin stories, the Holy People came to Spider Woman’s home, a skinny sandstone spire we call Spider Rock. At their behest, Spider Woman travelled to our four sacred mountains to gather materials: from Sisnaajiní in the east, she harvested wood; from Tsoodził in the south, she harvested plants to dye her wool; from Dook’o’oosłííd in the west, she learned weaving patterns from the thunder gods; and from Dibé Nitsaa in the north, she learned ceremonial prayers and songs to bless her weaving. And then the Holy People instructed Spider Woman to share this knowledge with the people, the Diné.

In this way, weaving was given to me.

Ted, the man who brought the rug onto Antiques Roadshow, knew admittedly little about the blanket’s history. The blanket had come to his family through the foster father of his grandmother. “It was given by Kit Carson,” Ted says with a flicker of a smile, “who, uh, I’m sure everybody knows his history ... ”

To see him smile, even if the smile is given in discomfort. To see Kit Carson flicker out of the showroom as quickly as he arrived. Kit Carson, the Indian agent who led a scorched-earth campaign against the Diné. Who burned villages and farms and slaughtered entire flocks of Navajo-Churro sheep. Who led a cavalry raid into Canyon de Chelly, a sacred place, where Spider Rock towers above the canyon floor. Kit Carson, who forcibly relocated those he did not kill to an internment camp in Bosque Redondo, where weavers spun yarn not from the wool of their sheep but from upcycled materials like bayeta, a red flannel cloth salvaged from the discarded uniforms of Spanish soldiers.

Textile scholars who write about this period of Navajo weaving describe it as a time of inspiration and innovation: new designs, new colours, new techniques. Some write of the freedom of commercial yarns and the relief that weavers must have felt, unshackled from the labour of shearing, carding and spinning wool. But when one of my weaving teachers, Lynda Teller Pete, talks about this period in Navajo weaving, it is easier for me to understand.

The land in Bosque Redondo was not fit for farming or for raising sheep. A quarter of the people interred there died of exposure, starvation and disease. Diné women pleaded with commissioners to return the people to Dinéteh, but they were forced to remain until four years later, in 1868, when they were finally given permission to begin the Long Walk home. Pulling these threads together now, reality emerges: the weavers were doing their best to spin shit into gold.

The Antiques Roadshow appraiser did not take into account the blanket’s loose association with Kit Carson; if he had, the blanket’s value could have inflated by 20 percent. His rationale: the link between the blanket and Kit Carson would be difficult to prove. But on one edge of the chief’s blanket, there was an important piece of evidence for its age and provenance: a small hole repaired by a weaver with thread spun from bayeta red.

A loom is a tool, a machine. An instrument of labour and productivity. It’s an object in which form meets function. At its simplest, a loom is an anchor; at its most complex, it is a network of wires, beams and circuit boards.

Once, “loom” referred more generally to any object valued for its frequent utility; English refined that meaning to a synonym for tool. “An outligger carryeth but onely one loome to the fielde and that is a rake,” a seventeenth-century farming book reads. From this book, I discover that an outligger was a girl who followed a scytheman through the fields to gather what he cut. I like to imagine each girl had her own favourite trusty rake, and then she passed that rake on to a cherished sister or friend after finishing her own role as an outligger.

An heirloom, then, is just this: an object whose form and function you hope holds value for the ones whose lives follow yours.

When my mother gifted me her mother’s blanket, my younger sister was jealous. She had only received a baby-blue polyester shawl, which my mother said she’d worn while dancing in ceremony. I might have preferred the shawl, but the blanket became a minor resentment that burbled under the surface of my relationship with my sister. I sent her the blanket a decade later, after our mother died. I wanted the gift to be seen as a gesture of pure generosity, but in my mind the blanket had been tinged somehow by the complicated nature of its value, which I found difficult to ascertain.

When I married my Canadian husband and left my desert home, I knew I wasn’t going to find the kind of weaving I had begun to learn in Arizona. Kitchener-Waterloo, sister cities bound by a hyphen, reminded me of central Pennsylvania, a place I thought I had left behind. To combat my depression during that first long winter, I enrolled in an introductory class offered by a weaving guild that rented floor space in a local synagogue.

My husband was skeptical. He has no inherent appreciation for handmade things, and I figure that he imagined our apartment cluttered with janky scarves that neither of us would wear. But the first hand towel I brought home — even with its uneven edges, clashing colours and skipped warp threads — began to sell him on the possibility of his wife as a weaver. One quiet morning, he even joined me at the synagogue to tie dozens of threads to another weaver’s old warp.

Tedium aside, the first thing that struck me was how fast this kind of weaving could be.

In Diné weaving, a loom is dressed for one project at a time. The weft is not one thread carried back and forth by a shuttle but many threads passed through the warp by hand. My weaving teacher’s hands reminded me of my mother’s: small as the bird they might hold, but strong. Diné weavers create tight, dense textiles by beating the weft threads with broad wooden combs, which creates a breathy sound of wood on wool that, my weaving teachers tell me, makes grandmas happy to hear.

A weft count of forty to fifty threads per inch is considered high quality; a fine Two Grey Hills tapestry must exceed eighty. Daisy Taugelchee, one of the world’s famous Diné weavers, could achieve weft counts that exceeded one hundred wefts per inch or more. The hand towels I learned to make, by contrast, rarely exceeded twenty wefts per inch, and the loom itself made this work easy. In the time it took to complete a Diné rug the size of a sheet of paper, you could finish enough hand towels to gift your mother-in-law, the mentors who wrote you letters of recommendation for a tenure-track professorship and the friends you sorely miss.

Shortly after the class ended, I joined the guild, which collectively owned and maintained a collection of both table and floor looms, including one so large it was best operated by two weavers seated side by side — but the guild was much more than its machinery. Any day I went, I could find women working. Sometimes they were quiet and focused on their individual projects, but other days they worked together, helping each other dress their looms or troubleshoot a problem. I was much younger than the other women, much less experienced, an apprentice to masters of their craft.

Less than a year later, I accepted a job at a university on Vancouver Island, and shortly after arriving, I looked up the local weaving guild. Their equipment was easy and cheap to rent on their website — $25 bought you three months on a floor loom you could take home — but unlike the guild in Kitchener-Waterloo, there was no communal space to work. Instead of joining, I decided to buy my own loom.

As soon as my quest began, I received more offers than I could accommodate. It seemed like every family had a deceased mother or grandmother’s loom in storage, an heirloom gathering dust. After a university function, a colleague told me about a floor loom that had once belonged to her mother-in-law, a master weaver from the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. Her husband held on to the loom hoping to finish her last piece, but thirty years passed and he never found the time to learn how to weave. This is the tension: a loom is simultaneously tool and inheritance, but it is often more one than the other.

A few weeks later, I came across a local listing: 45-inch floor loom, bench, warping mill, accessories. The loom was described as both beautiful and custom-built by the weaver’s husband, a cabinetmaker, in consultation with weavers. The seller said it was designed to reduce fatigue and maximize both tension and speed.

When I told my husband about the listing, he agreed to come see it with me.

The loom was dressed when we arrived. The weaver, a woman named Pat, invited me to test it out, and her husband, Mike, offered my husband a seat. I was nervous to weave in front of someone I didn’t know, but she didn’t hover too close. I tapped the treadles with my feet and slid the shuttle back and forth while she told me about herself and the loom, whose name was Charlotte. She picked the name from her memory of a grade-school teacher who read a chapter from Charlotte’s Web every Friday afternoon as a way of keeping her students’ attention at the end of the week.

Pat asked me about my weaving, and I told her about the Diné weaving classes I’d taken, the time I spent in the weaving guild, then she took me upstairs and showed me a Diné Wide Ruins rug she’d bought from a roadside stall on a trip to the Southwest. She didn’t have enough cash on hand, so she and Mike had to race between cash machines, skirting withdrawal limits, to pay for the rug on time. She told me the weaver’s name, Chimbah Nez, though I had to ask her to remind me of this name when we met again.

Pat told me the only reason she was parting with the loom was because of her hip; she was no longer able to work the floor pedals. At the end of an hour, longer than I had ever spent with a seller, I asked if I could take Charlotte. Pat agreed to let me have her.

A week later, my husband and I rented a U-Haul and drove Charlotte to my office on campus.

Pat first became interested in weaving in the early 1960s, when the clothes being mass-produced were both garish and uncomfortable. I worked in a vintage clothing store throughout high school and college, and it was the textiles made during this period that I hated most. The synthetic fabrics were fragile and collected static, which crackled in my hair as I moved between racks. But there was a woman in Pat’s church choir whose clothes she loved, and when she discovered the woman wove her own fabric, Pat knew she wanted to learn how. She didn’t begin until much later, when she was in her thirties, the same age as me, when she and Mike moved house and their next-door neighbours, Gladys and Jack, just happened to be weavers. Jack offered to teach her, and Mike asked her if she would like him to build her a loom.

Charlotte was built from pale-blond oak reclaimed from a World War II-era Air Force base. When some of the base buildings were demolished, the maintenance workers took the wood home. Mike arrived well after the demolition, but when he asked around about wood for a loom, one of the workers mentioned that he had some stored in his barn. He offered a trade: Mike could have the wood for a case of beer and an old power saw.

The oak had likely been harvested in the early 1930s or ’40s, and the planks were well-seasoned, straight. The wood had been painted with Air Force blue, which Mike carefully shaved away with a hand plane, though some blue freckles remained. He ordered a few premade components, like the reeds, but he hand-milled most of the metal bits himself. “Betwixt and between, it became a single entity,” he told me. “The loom was old before it was ever made.”

After Pat and Mike moved, she hardly used the loom he had built for her. She carried the guilt even after Charlotte left her possession. When I asked her why, she seemed startled.

“Well, I haven’t thought about it,” she said, but her mind started turning. She’d found the beginning, the learning, more exciting than the doing. “I didn’t love it enough,” she said, then laughed. “No one’s ever questioned my dilettantism before!”

I admitted that I hadn’t woven as much as I meant to, that I carried some of the same guilt. And the longer I didn’t weave, the more guilty I felt.

“Some of us aren’t able to focus on just one thing,” she told me. “I’ve judged myself harshly for that.” But for her, weaving was a portal, an entry point that deepened her appreciation for the way things used to be done: how weavers imbued culture and tradition into their work and art, and how both work and art reflected life and land.

Sitting there in Pat’s garden, sharing the shade of the umbrella Mike raised for us, I felt at home. Weaving, writing, birding, gaming—all had done the same for me. “Maybe Charlotte understands,” I said. Hesitant, because it was a vulnerable thing for me to say. But Charlotte, I hoped, might be a tool shaped perfectly for a dilettante and so, might be happy with me.

Everything, Pat told me, comes ’round again.

A little over a year ago, my husband and mother-in-law and I bought an old house together. She planned to live in the downstairs suite once she retired, and my husband and I above. He claimed one of the bedrooms on the main floor for his office, and I claimed the attic, whose slanted ceilings were too low for him. The north-facing skylight filled the room with a gentle light, and I painted the walls yellow, terracotta and Navajo white. It was easy to see myself weaving in this room come winter, and I was eager to bring Charlotte home.

Shortly before the fall semester began, my husband helped me dismantle the loom in my office. We carried her, piece by piece, to my small Yaris hatchback, and then he helped me carry her up the spiral stairs and reassemble her in the middle of the attic-turned-office.

I have big plans. Huck lace curtains for the bedroom. A rag-rug runner for the kitchen. New hand towels. Since my ADHD diagnosis, I have kept intense colour-coded daily schedules, and I am better at budgeting time than I used to be. I have made an effort to structure time for not-work things — birding, gaming, writing, weaving — and I have accounted for them all in shining yellow.

In the final pages of Charlotte’s Web, Charlotte, the spider, tells Wilbur, the pig, that her time is ending. Her last project is a delicately woven sac to hold her eggs. Surprised and amazed, Wilbur reveals he didn’t know Charlotte could lay eggs, but she remains cool, casual.

“Oh, sure,” said the spider. “I’m versatile.”

“What does ‘versatile’ mean — full of eggs?” asked Wilbur.

“Certainly not,” said Charlotte. “‘Versatile’ means I can turn with ease from one thing to another. It means I don’t have to limit my activities to spinning and trapping and stunts like that.”

Heartbroken but dutiful, Wilbur cares tenderly for Charlotte’s eggs after she dies. Come spring, they hatch by the hundreds — 514, to be exact. The spiderlings climb on top of the fence, spin a single strand of web and let the wind carry them off. Wilbur, in a panic, begs them to stay, but their small voices only cry goodbye, goodbye, goodbye as they sail away. Despondent, he collapses and cries himself to sleep, but when he wakes, he’s greeted by three tiny voices, three tiny spiders weaving their webs in the doorway of the barn.

Charlotte’s daughters. The next year, Charlotte’s granddaughters. And every year, daughters, daughters, daughters weaving their webs. ⁂

Danielle Geller's first book was Dog Flowers, published in 2023 (One World). Her work has appeared in Guernica, the New Yorker and Brevity. She teaches at the University of Victoria and at the low-rez MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. She is a daughter of the Navajo Nation.