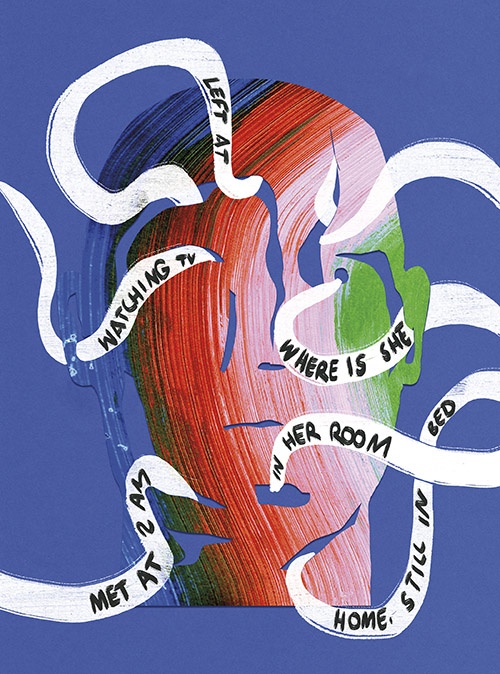

Illustration by Franziska Barczyk.

Illustration by Franziska Barczyk.

Busybody

I first became aware of my uncomeliness when I was a young man. The idea of anyone finding me attractive felt as far away a possibility as being struck down in my prime by a rare affliction (a not-unwelcome prospect). With my hunched shoulders and tendency to spit contributing to this picture of foulness, I knew that I had better uses of my time than finding a romantic partner who could overlook these faults. To add insult to injury, due to an untreatable skin condition my body was riddled with small clusters of skin tissue, making my appearance unpresentable and, frankly, sick-making.

I had one friend in the world who was not burdened by the sight of such physical infirmities, a man named Jens who was an average specimen of male beauty and confidence. I possessed nothing that he could exploit for financial or social gain, so I took his friendship to be honest and true. I had his every confidence in matters of love. I derived great satisfaction when he’d spare no detail in describing what transpired across the thin wall separating our rooms. As women would leave our shared abode in the morning, I would take pains to commit their bodies to memory, so that when Jens began his account later I could more clearly imagine his fingers gliding over their bellies or caressing their thighs.

There was no way that Jens was insensible to the power he held over me, but he did not strike me as someone who desired a pitiful reflection of his sexual prowess in another man. This made me loyal to a fault, willing to accommodate anything he thought to ask of me. When he required my assistance in monitoring the activities of a woman he was deeply interested in, I did not even consider what my moral scruples might have to say on the matter—I simply thought of how best to honour my friend while he sunk deeper into hopelessness.

Years after our various careers forced Jens and I into new living arrangements, I found myself cohabiting with several people. Over the course of a visit to these quarters from the city he had moved to, Jens fell in love with Ottiline, the most reliable of my housemates. I knew this to be the case because he did not want to share any of the intimate details of their lovemaking to me. I’d never thought of Ottiline in a sexual way before, but knowing that Jens was having his way with her made her body come alive in my eyes in a way I did not think possible.

As their romance became dramatically more serious, my lust started to fade. I no longer found myself obscurely attracted to Ottiline, even when I could hear them having sex as if I was in the room myself, such was the deathtrap-like configuration of our execrable lodgings. I was overcome by the perception that Jens was discovering a new dimension of happiness, and rejoiced that someone who had given me so much was now being rewarded in ways that I could not conceivably deliver.

Ottiline and Jens soon began to discuss marriage. Because I was aware that Jens had been speaking to other women, I knew the odds were equally favourable that he would go through with these plans as break them off. When, after a North African vacation with Jens, Ottiline came home in tears, I knew which version of events had transpired.

Ottiline viewed me with suspicion at first, but then disclosed the affair to me fully. I revealed what I could to maintain my friendship with her, but stopped short of betraying information that Jens would not want divulged. What followed were two harried months during which Ottiline and Jens lived separate lives that I was still a party to. When Jens was in town, he didn’t stay with us. I made sure not to tell Ottiline the company I was keeping, though she likely deduced his identity by the conspicuous nature of my omissions.

A few months later, during one such visit, Jens surprised me while we were drinking at Black Dice by asking me about his ex-girlfriend.

“How’s Ottiline doing? Is she seeing anyone?”

“She’s fine. She’s seeing someone new now.”

“Serious?”

“You’d have to ask her.”

“But to you—what does it look like?”

“It’s not what you had, but serious enough. They’re exclusive, as I understand it.”

We discussed the matter no further. A few hours later, I took my leave because I had work in the morning—I was a bathroom attendant at a reputable boutique hotel. Out in the street, Jens clapped my back affectionately.

“Keep an eye out for me. I’m interested to know how Ottiline is getting along with whatever-his-name-is.”

It didn’t dawn on me at the time that our friendship had evolved to include a transactional quality. Perhaps I did not want to admit to myself that this element was secretly at the heart of our association to begin with, which is not to say that it diminished its stature in my eyes—Jens was my friend and I never questioned my commitment to him.

When I got home that evening, Ottiline was with her new man Rory. They were watching a Dorothy Arzner film. I couldn’t stand Merle Oberon’s voice, so I excused myself to make an elaborate sandwich. Evidently, all my clattering around in the kitchen got on their nerves, so they went to Ottiline’s room. I didn’t know what Jens expected of me exactly, so I whipped out a notebook I found in one of my drawers and began scribbling the most obvious observations that came to mind.

I tabulated the amount of time Rory and Ottiline spent in her room, the film they had been watching (First Comes Courage), the fact that Ottiline went to use the bathroom after their lovemaking but Rory didn’t. My bed was angled so I could have a view of the kitchen if I left my door open; I saw Rory come out and rustle up a few drinks for himself, and made note of how many bottles were deposited in the sink. The following morning, I wrote down the time Rory left. I watched him catch a westbound streetcar at Claremont Street.

I faxed the entry to Jens and received no response for three-quarters of an hour. When it finally came in it read: “Good intelligence. Need more.” I didn’t respond immediately—I became interested in a news program on the television about human trafficking, and then hastened to make my way to work. All throughout my shift, I couldn’t escape a feeling of uncleanliness, like I had sullied my soul. I washed my hands seventeen times over the course of five hours. I returned home that night just as Ottiline was leaving. She told me that several faxes had come in, judging by the constant CNG tone blaring from my room. I felt especially corruptible during this interaction. The most recent fax had only six words: “Not enough chum in the water.”

Ottiline returned to the apartment with Rory in tow. They had a big row; he was pushing for more commitment from her. He wanted to know if she was still dating other men. When she would not give a definitive answer, he went into a rage and began slamming cupboards. The other housemates and I calmed him down. When we asked Ottiline what she wanted Rory to do, she said she wanted him to leave.

Rory left without causing more trouble. We all made jokes at his expense to help Ottiline come down from the contretemps. We shared a bottle of Mourvèdre, and I listened as everyone discussed their various relationship woes. Eventually Ottiline admitted that she wasn’t being fair to Rory, and that her mixed feelings over Jens were preventing her from committing to the relationship. We advised her not to give it any more thought. She seemed heartened by this.

I did not think about making new notations, despite the fact that several important impressions had dotted my mind over the course of the night. I simply gave in to the momentousness of the present with my friends. I forgot Jens’ request, and settled into the doldrums of life that are marked by periods of work and eating and sleeping.

A few weeks later, I received a call from Jens. He was irritated, judging by his tone of voice. He said that he expected more updates from me—at least four times as many.

“Rory hasn’t been over for some time,” I said defensively. “She might still be seeing him, but he hasn’t come around to the apartment.”

“Have you talked to her? How does she seem? Happy? Sad? Does she mention me?”

“You came up briefly the other day. It’s barely worth mentioning.”

“Let me be the judge of that. I’d love to get daily updates if possible.”

“I can do that. If I don’t send you anything, it just means I haven’t seen or heard anything, okay?”

“I hear you. I’ll be coming into the city next month. We’ll have a night out on the tiles.”

I began writing detailed notes about Ottiline and Rory. I was not disposed to an artistic frame of mind, and went in circles rewriting my thoughts in ways that I anticipated would please Jens. It was as if he derived pleasure from filtered access to Ottiline’s movements. I noticed that the more reports I gave, the more Jens kept away. I began experimenting with subjects that might entice him to come calling in person. I thought that if I began describing Rory in as much detail as possible, Jens would not only be overjoyed, but compelled to visit.

I catalogued Rory’s clothing and way of speaking, intimating his education and upbringing from what conversation passed between us. When Ottiline discussed Rory’s career aspirations, I was careful to commit these details to memory for later notation. Jens soon had a comprehensive understanding of the man who had supplanted him in Ottiline’s affections.

After a period of fleeting exhilaration, Jens grew tired of hearing about Rory. He asked that I devote further attention to Ottiline’s “frame of mind.” I did this with a perfunctory attitude, thinking that Jens would not be motivated to visit should I follow this course of action. The idea suddenly entered my head to fabricate a story about Ottiline, one that would not only bring this bothersome arrangement to a close, but impel Jens to crash through like a pistol shot.

I wrote to Jens in a frantic style of penmanship, detailing how it appeared to me that Ottiline was either about to break off her relationship with Rory or move in with him. I anticipated that this kind of dispatch would be provoking, and sure enough Jens called the apartment landline, something he had not done since being found out for a debauchee.

“Go ahead, Jens. You got my latest?”

“You have time to tell me about it? I understand if you’re indisposed or …?”

“It’s my day off. No one’s in the apartment except for me.”

“How can you tell that Ottiline is about to do something rash with Rory?”

“It’s not so easy to parse out for you, Jens.”

“Just work it through your mind. I don’t need proof. I just want to get a sense of what’s been happening.”

“She’s going away for winter break. Her parents are coming to pick her up this time. She’s going to ask their opinion on something.”

“What are you basing all this on? Something you overheard?”

“There was something in the flutter of her voice … it reminded me of when she told her mother that you were thinking of getting engaged. Maybe I’m reading too much into it.”

“No, no. You were right to contact me. I need to do something. I’ve been thinking about reaching out to her directly.”

The prospect of being outed as a snoop turned in my mind.

“I didn’t realize this was something you wanted to pursue.”

“You don’t know quality until you’re picking out canner from your teeth. My father used to tell me that. Maybe I’ve just grown sentimental. I miss Ottiline. I’ve come around to thinking that she was right for me in every way.”

I heard a set of keys at the door. I put my hand against the receiver as Ottiline stomped into the foyer.

“Did you hear me?” Jens continued. “What do you think? Should I write her a letter, or come down to the apartment?”

“I have to go now,” I said into the receiver. “I’m not interested in an in-person installation, but if you want to send me some literature on the matter, I’ll give it a read.”

A few weeks later, a letter addressed to Ottiline arrived. I was the first person to pick up the mail that day, and I recognized the childlike scrawl—the reticence that showed itself in all of the d’s and b’s because Jens still got confused between the two. I weighed the letter carefully in my hands, and considered throwing it out. Jens didn’t call me for some time afterward.

I considered ending my dealings with Jens on the grounds of my growing mortification. There would be little ill consequence at this juncture to end this game of busybodying. I’d have to deal with Jens’ moping and solicitousness until he forgot about me, but I would be rid of the feeling that on returning from a long day’s toil makeup assignments awaited me.

I kept Jens’ letter underneath a pothos in my room. Ottiline and Rory came to the apartment together often, their rift having ended as quickly as it started. After about a month Jens resumed contact, asking me if Ottiline had received the letter. He speculated that it was lost in the mail. I grew weary of the one-sided nature of our relationship and unplugged the fax machine. Many calls came, but whenever someone other than myself would answer, Jens would hang up.

My housemates attributed the reason for the calls to me, and I took no pains to disabuse them of the assumption. Two weeks went by before a second letter arrived, this time addressed to both Ottiline and myself. Ottiline and Rory were the only people in the apartment when I came home from work that night.

“What’s this?” Ottiline asked me.

“Let me see,” I said, trying not to let on that I was beside myself with embarrassment.

I took the letter from her and verified that it had not been opened. I turned away without saying anything more and went to my room, locking it. I ignored all of Ottiline’s entreaties and drowned the noise of her knocking with a CD of ambient whale songs Jens had given me, turning the volume to the loudest setting. I curled into a ball on my mattress. The letter felt as heavy as the hand of death.

The next morning, I called in sick to work. Once everyone had left the apartment, I destroyed the incriminating dispatch. I was about to do the same with Jens’ original letter, but could not bring myself to do it. It felt like self-violence. I placed it on Ottiline’s bed, realizing that it was the only way out of the situation.

After Ottiline returned home that night, she knocked on the door of my bedroom and asked to come in. She showed me the letter, which I scanned quickly. The words “love everlasting,” “grievous mistake” and “eternally regretful” were underlined in red. “Take me back” was repeated several times.

“How long have you known about this?” Ottiline asked, now understanding to an extent my behaviour from the night before.

“He mentioned a desire to approach you,” I said repentantly. “I didn’t want to interfere.”

“There’s a wicked sense of entitlement to all of this. To the timing of it.”

“Do you want my opinion on it?”

“Yes, but you should know that it might not factor into my decision at all.”

“I think he’s sincere. About wanting to get back with you. But sincerity can only be a consolation. It’s never the reason you get out of bed in the morning.”

“Does he know about Rory?”

“I didn’t lie about your eligibility. Should I have?”

“I just want to know where I stand.”

Ottiline walked out of my room to give the matter the deliberation it deserved. I was further struck by the unseemliness of my position. I believed that I was owed little more than the circumstances I found myself in, but another part of me—perhaps one that secretly held on to the idea that there resides within every human being some innate form of nobility—believed that I had been debasing myself with matters undeserving of my notice.

I picked up a pad of paper and a pen, and jotted down the first observation that I’d ever had about my own life. ⁂

Jean Marc Ah-Sen is the author of Grand Menteur, In the Beggarly Style of Imitation and Kilworthy Tanner. His writing has appeared in Literary Hub, Catapult, Hazlitt, Maclean’s, the Globe and Mail and elsewhere. The National Post describes his writing as “an inventive escape from the conventional.”