Jeanine Brito, Some Vivid Dream (The Artist), 2024; image courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, photo by Shark Senesac

Jeanine Brito, Some Vivid Dream (The Artist), 2024; image courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery, photo by Shark Senesac

Portrait of a Girl

Contemporary women artists are painting over the naive pictures we have about girlhood.

Last year, the pink bows took over. Themes of girlhood dominated pop culture in 2023 as Barbie broke box office records, kicking off a season of hot-pink everything. Designers took the coquette aesthetic—think dainty and feminine styles like puff sleeves, pastel colours and lace—to the runway. Beyoncé and Taylor Swift glittered up stadiums and overwhelmed the Ticketmaster website with their world tours. Think pieces declared 2023 “the Year of the Girl,” a celebration of all things feminine.

The paintings of Jeanine Brito, who grew up in Canada and is currently based in Belgium, feature the same wrinkly ribbons and gowns that have filled many women’s Pinterest boards and TikTok feeds during this latest hyperfeminine wave. But unlike pop culture’s shiny image of girlhood, which casts it as a paradisiacal period of naivety and freedom, Brito’s art is almost nightmarish. She lays bare the horrors of that stage of life, depicting lambs awaiting slaughter and blood spills on countertops. Brito believes in exploring the danger and darkness inherent in the glittering fairy tales and storybook myths we tell about girlhood. Her works expose how these narratives leave women with hollow, unrealistic images to live up to.

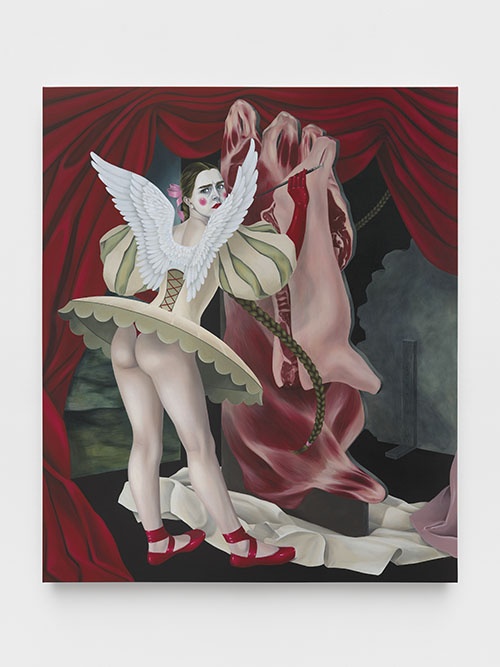

Brito’s latest solo exhibition, The Grumpy Girls, opened in New York City this spring. The show featured a collection of surreal and theatrical paintings that pull back the curtain on the performance of femininity and highlight women’s agency. In one painting, Some Vivid Dream (The Artist), a figure wearing a tutu glances over her shoulder at the viewer. Her pale ass is fully visible, a cheeky nod to the sexuality she’s claiming and displaying. The figure paints rivulets of fat onto a giant cutout of a hunk of meat. The furrows between her brows convey a sense of anger and frustration, almost as if she’s annoyed that the viewer has interrupted her work of fantasy.

The women in The Grumpy Girls’ paintings aren’t merely players on a stage—they’re creating their own production, working on an elaborate stage set while braiding hair. While many of these women are adorned with the now-ubiquitous pink bows and ballet shoes that constitute popular images of femininity, these icons are accompanied by grotesque props like a rosy steak and a glass bud vase filled with blood. The menacing images underscore just how far these grumpy girls will go to render their production repulsive to others and truthful to their own selves. They are intent on revealing an uglier, realer and bloodier version of girlhood, and reconfiguring the playacting that women do in the real world.

Brito is part of a coterie of contemporary female artists receiving accolades and praise for their complex representations of girlhood. While Brito and her contemporaries draw on the iconography of girlhood that prevails in pop culture today, their works pervert the picture-perfect portrayals that frame girlhood as an idyllic period. Instead, these artists delve deeper into the more difficult, darker reality of what it means to be a girl, exposing the pressures of catering to the male gaze and of living up to expectations of perfection. In a culture saturated with romanticized, simplistic visions of girlhood, these nuanced portrayals expose the constraints imposed by the patriarchy and make space for more expansive, authentic and challenging expressions of femininity.

Artists have used symbols like the ballet shoe and hair ribbon to conjure the image of the perfect girl for centuries. Self-styled realist artist Edgar Degas—a contemporary of nineteenth-century French impressionist greats like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir—famously depicted dancers in the Paris Opera and its ballet school, capturing the delicate tutus and poise of ballerinas on stage and behind the scenes. His paintings are celebrated by many as beautiful renditions of the sweet, innocent world that girls inhabit.

But Degas’ works belie a darker, more grotesque reality. Many of the students at the Paris Opera ballet school—who were nicknamed petits rats—came from working-class backgrounds and joined the school in hopes of escaping poverty. The opera was a cruel environment, frequented by older men who were known as the abonnés—patrons—of the ballet. The abonnés prowled in the audience and backstage, making the school a men’s club of sorts. Succeeding as a dancer often meant learning to secure the abonnés’ favour, since they held the key to resources and opportunities to advance in the school.

This dark side of girlhood lurks in several of Degas’ works. A hazy late-1800s painting features a young ballerina mid-performance and a tuxedoed man standing just offstage, his face hidden behind a yellow curtain. In another, men in suits watch from their chairs as ballerinas rehearse nearby. While Degas’ works may seem to depict the ballerinas’ freedom, the explicit inclusion of the men for whom these young women were performing tells another story. Rich, powerful men were the ones buying and displaying Degas’ work, and their interests shaped the paintings, just as the abonnés pulled the strings in the dancers’ lives. Degas himself has been accused by some art critics of being a misogynist.

The threatening omnipresence of the patriarchy that haunts Degas’ paintings is at the heart of what it means to be a girl. Girls are expected to embody a sense of innocence and fantasy. They learn to conceal what may be perceived as ugliness, whether it be poverty or the reality of gender oppression, and to mask it with ribbons and rouge. But contemporary female artists like the Calgary-born painter Anna Weyant unpack the connections between the beauties and horrors of girlhood. Weyant's works explore both girlhood’s glossy, artificial touches—dark lipstick, wide lashes—and the more macabre—a bandaged hand, broken glasses.

Weyant paints doll-faced women with the blushing cheeks and silky hair of cartoon princesses, but she also plays with humour and uses Looney Tunes references to convey more subversive messages. Her 2023 painting May I Have Your Attention, Please? features a black-eyed girl with a pointed nose, reminiscent of the Whos in Dr. Seuss’ children’s books: whimsical, benevolent creatures who aspire to spread cheer. But Weyant’s Who-ish girl, despite her wide smile and ribboned hair, is decidedly more unsettling. She’s smiling at someone or something just beyond a cream curtain, and the iris-less eyes and blackness of her pupils lend a feeling of artifice to her happiness. She exudes a manufactured delight, the kind the petits rats and other girls have likely learned to spin up on command.

Another Weyant piece, This Is a Life?, features a vase of wide-petaled daisies. Daisies could be the little girl of flowers: they’re not as romantic as roses or as funereal as lilies, but are pleasant and faintly scented, simple and innocuous. The painting's titular question floats above the daisies, the words pulled from a title card used in a 1955 Looney Tunes animated short. In that cartoon, Bugs Bunny takes the stage to wax philosophical about his idyllic childhood and subsequent life of mischief, presenting a rosy retelling that echoes the glamourized versions of girlhood in pop culture.

Weyant challenges us to look more closely at these idealized stories. Her paintings may feature emblems we recognize, but she often includes a twist that disturbs or shocks the viewer. The daisies in This Is a Life? look like they’re made of plastic, and their artificiality almost demands that the viewer look closer for confirmation. The strangely perfected fake flowers recall the lacquered smiles of Weyant’s girlish subjects. Shoved into a dismal, realistic world, the brightness of the petals seems tinged with an eeriness. This Is a Life? reveals the hollowness of the unrealistic stories women tell themselves about their childhoods, prompting us to see past the trappings of happiness and perfection.

Both May I Have Your Attention, Please? and This Is a Life? feature swathes of inky blackness that disturb with their opacity. Weyant uses this same darkness in the backgrounds of her portraits of women. Often, the subjects—a laughing blonde woman drinking wine in Loose Screw, or a pair of identical women in nightgowns in Two Eileens—may appear peaceful. But the penetrating blackness surrounding them seems to be closing in, threatening to reveal the abonné every girl knows to be waiting in the wings. Of course, there’s never just one abonné; like the consuming darkness that surrounds these women, the patriarchy is everywhere, enforcing a fantasy version of girlhood that men want to see.

As viewers, we can deny that darkness its power by confronting the feelings that paintings like Weyant’s inspire in us. Looking at her portraits of women, I’m struck by the sympathy and understanding I feel for her smiling, twisted subjects. Too many of us have already contorted ourselves in the gloom of a male-dominated world.

While artists like Brito and Weyant seek to expose the performance of idealized girlhood and femininity, others work to subvert the expectations that girls and women are held to. Mira Mariah is a Manhattan-based tattoo artist who works under the name Girl Knew York. In the summer of 2023, her solo multimedia art exhibition Girl Pain was shown at the Rockefeller Center, a multipurpose complex and tourist magnet in New York City. The exhibition played with feminine beauty standards and conveyed a sense of what Mariah calls "the off-putting” through ceramics, drawings and more. There was a mirror etched with dancing girls, and sculptures covered in Sharpie-drawn Girl Knew York tattoos. While marble statues of women have long been upheld as epitomes of beauty and femininity, Mariah’s ceramic versions are more imperfect—the linework doodles and face tattoos disrupt traditional notions of beauty.

Mariah’s identity as a disabled queer Latina woman plays an enormous role in her art. She says she sits quite comfortably with the juxtaposition of ugly and pretty that others may find unnerving; this disruption of an expected image is fundamental to the work she made for Girl Pain. One of Mariah’s paintings features a white-veiled woman smoking a cigarette and cradling a fish, challenging conventional depictions of brides as perfect and polished. In another work, a giant pink-and-white bow on the backrest of a black wheelchair turns it into a chariot of luxury.

Even while many contemporary female artists challenge patriarchal structures and ideas of beauty, the subjects they paint are often white or have lighter skin. Their pale faces are the ones most closely associated with the perfected girlhood that society wants to protect, and their beauty is valued above that of Black and brown girls—even in art that is meant to be subversive. But Mariah’s centring of women of colour and disabled women in her work puts forth a more expansive view of girlhood and who it encompasses. Her art reclaims the beauty that society often denies disabled people, people of colour and others on the margins, challenging pop culture’s sanitized and constraining portrayals of girls.

One work in Girl Pain features an image of a gold cup trophy, the kind handed out at school sporting events and spelling bees, festooned with spindly black ribbons. Etched on the trophy is the title of the piece: #1 Girl. Throughout history, women and girls have known what it means to be pitted against one another, competing for the attention of men and the favour of society. It often feels as if there can only be one girl at the top, the one who best performs the ideals of femininity.

Rather than competing, Brito, Weyant and Mariah’s work joins that of other contemporary artists trying to make room for more authentic, diverse representations of girlhood. As the art world reckons with a centuries-long tradition of prioritizing male artists, the success that these three artists are finding is telling. In making work that accurately reflects the lives of women and girls, they’re creating a market all their own.

I’ve always loved the titles of Brito’s paintings. Each evokes the juxtaposition between the darkness and light of girlhood: Gentle is the knife she wields so nicely. The Feminine Urge to Sacrifice. Passage Through Girlhood. The harshness of “knife” sits comfortably alongside the familiarity of “gentle” and “nice.” “Feminine” and “sacrifice” entwine.

The Grumpy Girls exhibit introduced a new favourite title: You Remember Too Much. In the foreground is a porcelain-skinned woman, her intense gaze fixed on something we cannot see. Above her head, her braid creates a second frame of sorts. Within this frame, eight gleaming pearls orbit a Cinderella-esque castle, complete with turrets and craggy cliffs. A wilting pink bow wrapped around the braid crowns the painting.

Looking at the work in New York City’s Nicodim Gallery, my eyes lingered on the painting within the painting, the one surrounded by that ribboned braid. The castle seemed to hold all of the braid-wearer’s secrets, keeping them safe forever. I felt the familiar pang that comes from thinking of the girlhood memories I’ve locked away for safekeeping: the pure and joyful ones, yes, but also the failures and betrayals and moments of hot shame. For so many years, I cracked my joints as Degas’ petits rats did, trying to push everything ugly and unglamorous out of the frame. I wanted only to see the glitter of manufactured perfection.

But as Brito, Weyant and Mariah’s work challenges us to see, that shellacked vision is ugly in its own way. It’s better to keep the blood, guts and darkness in sight, so that you can remember the path you’ve carved through the woods. That knowledge feels important to my survival. Without it, I’d only get further and further away from the girl I used to be—and she is a part of me still.

As adult women don hair ribbons and ballet flats, perhaps they’re doing the same reminiscing as those visiting the works of female artists who depict themes of girlhood. These women are remembering a little too much for society’s liking, recalling the complications woven into that supposedly picture-perfect stage of life. They’re making sure they won’t forget. ⁂

Julia Carpenter is an award-winning journalist living in Brooklyn, New York. Her writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Esquire and Glamour, among other publications.