Illustration by Rosalie Maheux

Illustration by Rosalie Maheux

Pegasus Mind

In the grim limp of late January, a week after I took my Sacred Oath, the other Paige Cooper released another book. The plot concerned a voluptuous border guard who shared a telepathic and erotic bond with a pegasus named Ibidem. I was, as always, both ragingly envious of the idea and mortified that someone—my dental hygienist, a friend’s student, a conversion-rate optimization consultant at work—would mistake the horse porn book for mine. It had happened before. Frequently enough, in fact, that whenever I identified myself as a writer I’d barely mutter the name of my own juvenile effort before pivoting to describe and decry the other Paige Cooper’s massive oeuvre. Most recently, I’d cast Ensnaring Strike—my go-to hook-up spell—on a halfling fingersmith after an evening of queer francophone stand-up. I took his arm in the drifting snow, invited him up for a nightcap, and found myself handing him a copy of Dragon’s Lover. “Are you sure it’s not yours?” he’d asked, glancing at the golden-hour torso on the cover before flipping through to the sex. “If it was,” I said, “I wouldn’t have to get up for work tomorrow.”

I spent a few days sulking morbidly, until I remembered that when I first moved to Montreal, I’d written a short story about a mounted policeman whose horse had talons and wings, presumably a beak. A hippogriff, gelded and masked against tear gas. Of course, I’d buried my equine fantasy in protests, strip clubs, police violence and STIs, because the policeman was modelled after an ex, and I’d had complaints to lodge with the cosmos. The gelded steed—Bucephalus?—was a confusing metaphor. Still, I’d done it first. The other Paige Cooper had copied me. Yet, according to my queries, the internet preferred her version to mine by an order of magnitude.

I complained resonantly of this injustice that weekend, when our raiding party gathered in a lamplit kitchen to drink nano IPAs and argue about who’d lose their jobs to AI first: those of us acquiring users in the click mines or those of us teaching the youth to approximate human syntax in five-paragraph essays. Our party was down to three: me, and a pair of elves—one a highborn battle wizard, and the other a sea elf urchin with Level 2 Madness who believed that she was a Chaotic Evil barbarian. I myself was a centaur paladin—knight and steed in one body—and now that I’d taken my Sacred Oath my mossy deity had imbued me with additional forest-themed healing and combat magicks such as Speak with Animals and Commune with Nature. My horse half was a splendid lavender destrier, fifteen hands tall at the withers, decked in embossed scale armour and black barding. My human half needed a haircut and didn’t wear a bra.

Our party hadn’t gotten together since our dungeon master, Greg, moved out east. Living without a campaign was easier for some of us than others. I often wondered whether Greg missed us enough to resume, but even if he was amenable, the battle wizard had Zoom fatigue and waved off every plea to meet. Meanwhile, the sea urchin had fallen in love with a human man from another party whom she claimed was a king, though when I asked him he told me he was actually a war cleric who’d found a crown in a burned-out blimp. The crown made him especially smart.

“Sue her ass!” cried the sea urchin, midway through my scroll of grievances about the other Paige Cooper. “Lawyer up!”

“Steal her identity, hack her Amazon account, take the royalties, and change her pen name to Turdy Bird,” said the battle wizard, whose fireballs all came from a spellbook called Wikifeet, which he wore on a golden chain around his neck.

“Why,” said the war cleric, “don’t you just rewrite it?”

“What?” I said.

“If you like the idea, why not write it the way you’d want it written?”

I made a considering face and changed the subject. The next day, off-camera during the biweekly down-funnel squad sync, I bought a PDF copy of Pegasus Mind for $0.99.

Their mirth quickly turned to molten heat. Lyssa gasped as Ibidem tossed her down into the straw. His tongue sought out hers and they twined together in an erotic dance. She clung to him and their bodies undulated as they kissed-—endless, long, hot kisses meant to prolong the agony of their desires.

There was barely a catch as he broke through her maidenhead.

As soon as she felt him pulse inside her, Lyssa began to come. Her body burned, feeling him come in wave after wave of delight, fueling her own bliss as nothing else ever could.

They were coming again when they heard the voices. Male voices headed in their direction. Lyssa blushed as Ibidem moved away from her. He quickly set her behind him as four guards rounded the corner and stopped short, staring.

I wondered if it was a common misapprehension that penile ejaculation is palpable in the vaginal vault. At age fifteen, redolent in virginity, I’d written something similar in Arolos Weyr—a Yahoo! listserv dedicated to role-playing in the world of Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series. I also wondered if Ibidem was still a pegasus in this scene. Perhaps I had missed a paragraph where he shapeshifted for coitus? Probably that choice—shapeshifter or full-time equine—ought to be telegraphed in the cover copy: either choice would attract an entirely different readership.

“Who owns the net-net nurture flow?” said the Senior Director of Customer Operations. “Paige? Is that organic lifecycle?”

I turned on my mic. Twelve people in the meeting and my only ally was Jean-Pierre from Go-to-Market. The hostiles from the Expansion Org outnumbered us: they’d brought two Senior Directors and an SVP. The SVP had a blurry American flag hanging on the wall behind her. My VP was out-of-office at an on-site in Zurich. This was not a surprise attack so much as a scheduled skirmish in the forever war between two irreconcilable growth strategies, both of which had stopped delivering since AI superseded our software a few months back. Numbers no longer went up, or even stayed flat, and the business had yet to decide whose fault that was. The business was confusedly examining itself, looking for the problem like a bonobo hunting down a tick while the forest burns. Still, no one wants to be the tick. To this end, the Expansion Org preferred a hideously effective tactic: publicly prosecuting the minutiae of our team’s work.

“Great question, Vicki,” I said. “Let me get back to you on that.”

I turned off my mic and Slacked my direct report Nathalie, who didn’t have to attend business LARPing meetings because she ran a team that did actual work. I typed: Who owns the net-net nurture flow?

Vicki does, said Nathalie.

I debated whether to tell Vicki privately or publicly. Privately, I decided, because I hadn’t known if it was mine, either. I opened the PDF again.

Colonel Magnus looked upon the three pegasuses that had come to the Silver Creek border station curiously. It was obvious to say that he’d never met a pegasus since he’d been born after they’d been declared extinct, so he didn’t even try to pretend he had no questions for these unusual mythological beasts that most people had believed to no longer exist.

It irritated me that the other Paige Cooper hadn’t even bothered to describe the colours of the pegasuses. Palomino? Blood bay? The options were stunningly rich. Soft ivory wings with golden sunrise primaries. Leathery bat wings the colour of old wine. I often bewitched myself pondering how my own lavender hide darkened to violet points at ankle and tail.

When the funnel sync ended, I scheduled a Slack to send to Vicki in seven hours, 21:07, so she’d think I worked late and also so she wouldn’t respond: lol turns out your team owns NNN let us know if you want advice on optimization.

I ground more coffee, and while it dripped, I bought a PDF copy of Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonsdawn, for $7.99, which I’d first encountered in the public library in grade four. I’d brought it to school and read the sex scenes aloud to classmates at recess, thereby hitting the peak of my personal popularity for the next eight years. McCaffrey’s dragons came in an uncompromising hierarchy: female dragons were vast golden queens or tiny, slutty, infertile greens. Male dragons were bronze, brown or blue, in descending order of size, virility and status. When the golden queen rose in her mating flight, the bronzes and browns would chase her, and every dragon and dragonrider in the Weyr would be possessed by a mass mania of telepathic horniness, which was not exactly an orgy. Then, when the golden queen laid her eggs, a troop of pubescent humans would line up to impress the hatchlings, who could smell their sexual preferences. If a boy telepathically bonded with a green hatchling, one day she’d rise to mate, and he’d be gay by virtue of being a bottom to the rider of the blue or brown that caught her. Late in the series—when the books were written by McCaffrey’s heir, Todd—a girl bonded to a blue. I was stricken by the gravitas of this. In art class I painted a regal portrait of her in oils. On the Arolos Weyr listserv I made up my own blue-rider, and composed long emails about her sex life, topping all those wanton greens. Obviously, all the dragons were telepathic with each other and their special person. If your dragon had sex, you had sex. If your dragon died, your friends helped you kill yourself.

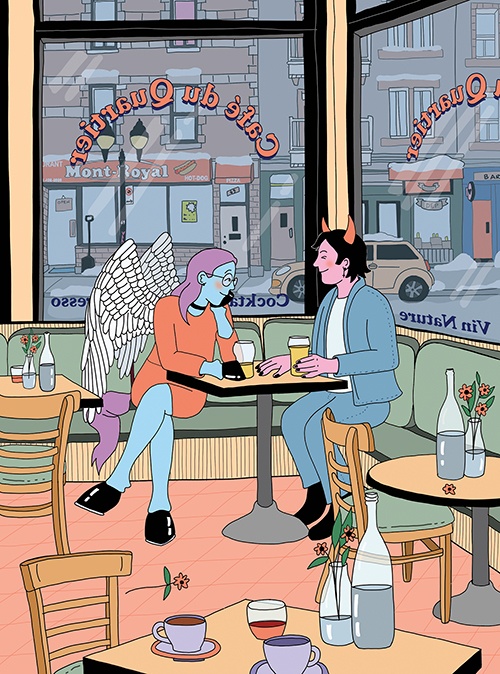

My halfling lover and I had agreed to meet for another date. He was new to the city from the Maritimes, and he had better credentials than me in both blue-collar work and activism, so I picked a popular, unpretentious place where I thought we’d both feel anonymous—neither too queer nor too straight. I understood that I was overthinking things. I was both eager and anxious to be seen alongside him. I drank one pint fast before he arrived, and another before we ordered food. It was his turn, but he proposed I cast Zone of Truth. I braced myself to be unflatteringly revealed.

His question was: “What would your preferred anthropomorphic feature be?”

“Oh,” I said. “Wings I guess?”

He narrowed his marshy gaze at me. “What kind of wings?”

I stumbled to be casual. “Maybe bat? Or maybe just traditional. Swan, angel, whatever. What about you?”

“Um, satyr horns. Or like, antlers.”

I imagined Faun Tumnus with his red wool foulard, his dewy, sensitive eyes, his hairy little belly and stamping cloven hooves, twitching tail. It had been blizzarding outside for weeks. The way back to my place was a lightly carved wyrm tracing over hip-deep snow.

“So you’d shed the antlers every year?” I asked over my shoulder as we trudged, single file.

“You know that actually only happens through adolescence. At a certain point they just stay on all year and keep growing.”

“Oh,” I said, annoyed. I’d never slept with someone who knew more about deer than I did.

But at some point that evening I must’ve cast Warding Bond, because I’d made him incontestably mine. We lay in bed staring wide-eyed into each other’s faces, and solemnly deleted the apps off our phones. It wasn’t just the hours spent nuzzled up each other’s cunts, or that I slithered charmingly out of bed at five-thirty to drip coffee and pack him a lunch. I hadn’t dated a person with a real job—one that involved putting on a belt and walking to the metro—in over a decade. I kissed him goodbye in my bathrobe and put myself in the shower, which he’d left neat and dripping. I hoped I’d left him stumbling, giddy, helpless to explain his tardiness and Tupperware gnocchi to his coworkers at the sex toy warehouse. When I logged in to my meetings, on the other hand, I was just haggard and suspiciously smiley.

I spent the day trying to describe him to my party. A sylvan nymph, I typed. Red Green, but a twink.

Later that week, when it was his turn, the halfling brought me a gift from the warehouse: a sproingy, emerald-green strap-on.

“I guessed at the sizing on the harness,” he said. “I didn’t know how you’d want to wear it.”

“What do you mean,” I said, apprehensive about which parts of me would bulge.

He hesitated. “Because I know with pants, for instance, your kind has a few different options.”

“My kind?” I said. I examined the supple leather and glinting metal: tools of equine control. “This better not be bridle leather.”

When my turn came again, I cast Aura of Purity and the halfling and I spent a few days apart, washing sheets, eating healthy meals, listening too closely to song lyrics. I gave some thought to how McCaffrey’s dragon sexual hierarchy had circumscribed me, like a mother tongue, before I could even parse it: smug, bossy breeders at the top, horny queers and moody straight women at the bottom, with a deep layer of incels in between. The snow was continuing to fall, re-arranged into alpine formations and rollercoaster sidewalks by neighbours and snow plows, so I found my copy of Mary Ruefle’s poem that starts, “Every time it starts to snow, I would like to have sex,” and sent it to the halfling. At work, the Expansion Org was machinating something terrible—fortifications, weaponry—and every time Jean-Pierre and I met with our VP, he looked increasingly punished, until one day his icon was deactivated. Now I was to report to Vicki, who’d hung an American flag in her office, too, and gave me a new, worse title: something like Senior Manager of Nurture. Senior Manager of Value-Add Touch. Senior Manager of Being Finely Attuned. First-order imagination is the realm of the senses: being able to call up an image of a horse. Second-order imagination is reconfiguring perception to create a new idea: a horse, but it has wings. I can’t remember what third-order imagination is, but it seems like probably no one uses it anymore, anyway.

On Monday evenings, the sea urchin and I attempted to improve ourselves through various processes, like yoga, tai chi, meditation and sober vegan suppers. That week, as we waited outside a temple in the soft blizzard, the sea urchin sighed and kicked a snowbank. “When are we ever going to have another adventure?”

“I could invite the halfling to join our party,” I told her. “He doesn’t have one right now.”

“How’s it going with him?”

“Ah,” I tried to be coy. “It’s really nice. He burst into tears the last time I was inside him.”

The sea urchin squinted. “What’s a fingersmith again?”

“A pickpocket? I guess we don’t really need two of those.”

“I’m not a pickpocket. I’m a barbarian.”

“You want to invite your war cleric?”

“And have two of you laying on hands? Nope.”

Under normal circumstances, an elementary healing spell like Lay on Hands did not take much magic at all, but with all the coming and crying the halfling and I had been doing, I’d actually run down my pool of healing power and needed a Restoration, Lesser or Greater. I didn’t admit this to the sea urchin because it seemed crass, or vain, to admit how much I’d been using my blessed touch on the halfling’s little body. His little body, which had become very precious to me.

Inside the temple, the priest commenced, and we shuffled in, our hands in the cosmic mudra.

It wasn’t until hours later, when we’d finished tidying the nun’s kitchen and brushing the nun’s hound, that I checked my phone and saw the video the halfling had sent. It was choppy and distorted and the audio didn’t play at first. Masked shadows flinching through pastel veils of smoke. Canisters cracking in the icy, dead-end square. In the video, my halfling was pale and red-eyed, stuttering in Chiac. Two dozen buses carrying helmeted riot police had met them. Troops lined the curbs as the marchers passed. Drones overhead. Then stun grenades, then tear gas. The protestors were very young, mostly students, mostly masked, and they’d panicked like they were supposed to. Yes, the Hôtel de Ville had flown a flag to mark this year’s Trans Day of Visibility. Yes, the posters had advertised the march with a drawing of a burning squad car. The police in their robocop armour had a special way of throwing you to the ground before you knew they’d even marked you. The kid beside you, wearing a pink balaclava, pinned face-down in the cobbles and slush. Somehow, my halfling fished through the cordon, down an alley and away. On the news, the police explained that what happened was the protesters set off fireworks.

It took days. He wouldn’t see me. He bathed in milk. He went to work. He experienced periods of unconsciousness. I fretted, laving myself in guilt: I hadn’t gone, I hadn’t known he was going, but he hadn’t invited me, why hadn’t he invited me. In the quiet without him, I resorted to the war cleric’s idea: I began rewriting the other Paige Cooper’s book. I described their gleaming haunches, their soft muzzles and eager teeth. I described what it’s like to stand before a creature and be chosen; what it’s like to know everything about that creature without suffocating under the weight of that knowledge; what it’s like to bathe in the silver light of being clearly perceived, and entirely forgiven.

When the halfling came back to me he could smile again. He brought a trench shovel. We dug out a snow tunnel under the six feet of powder on my balcony. The tunnel maintained integrity all the way to the empty cavern underneath the picnic table, and in that frigid chamber we sat on dampening quilts and looked out through the railing across the crusted rooftops of the neighbourhood to the golden lamps of far-off kitchens. It was my turn: I cast Zone of Truth again and we talked about our friends who’d killed themselves and the times we’d tried ourselves. I cast Moonbeam and the beauty of this place we’d made fell in on us with a keening, somatic anguish. I cast Hallow, and we ceased to be frightened. I laid on hands. I laid on hands.

My Sacred Oath, vowed the week before we met, went like this:

I should name myself

For thirty years I have suffered disgracefully

Vast emptiness, nothing holy

Moons and flowers the true masters

How many times have I gone down to the dragon’s lair to search for you?

It’s too early to despair; it is always too early to despair ⁂

Paige Cooper’s debut collection of short stories, Zolitude, was up for several awards in 2018, including the Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction.