What is an Album, Anyway?

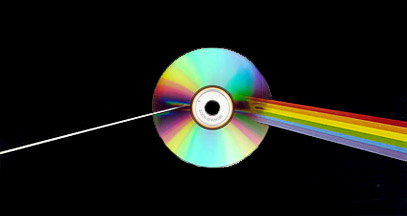

Last week, a British court decided in favour of British icons Pink Floyd in their lawsuit against their record label, EMI. The issue at hand was the band’s opposition to their albums being sold online piecemeal song-by-song, something that the most major online music stores, such as iTunes, allow.

They’re not the first artists to oppose this practice; it’s the reason why AC/DC and Kid Rock are nowhere to be found on iTunes, for example. But those are active artists with some sway over their back catalogue. In Pink Floyd’s case, the records were made available for sale on iTunes without their expressed consent and in spite of a clause in their contract designed to “preserve the artistic integrity of the albums.” So they sued, and they won; not surprising when put against EMI’s silly argument that the clause only applied to “physical” releases.

The result of the decision is that Pink Floyd’s music can no longer be sold as single downloads or as mobile ringtones. A win for artistic integrity, right?

I’m not so sure.

I’m saying this as someone who believes strongly in “the album” as an art form, and as someone who still generally listens to albums start-to-finish more than I do playlists or shuffling. And, obviously, the legal decision was the right one given the band’s contract. But Pink Floyd’s insistence on the clause in that contract puts them at odds with not only how people listen to music today, but how they’ve always listened to music. And I think that’s kind of stupid.

To start, on what planet has the “artistic integrity of the albums” ever been preserved? Until recently, radio has been the primary gateway for discovering new music, and radio has always had the power to pull apart albums and choose particular tracks to emphasize. Think about how people have discovered bands like Floyd or AC/DC from listening to rock radio. Let’s face it: 45 minutes is a LONG time to invest in discovering a band, which is why the single is so enticing.

And on that front, things really haven’t’ changed that much in the digital age. Yes, it’s great that sites like NPR and AOL will often stream full albums for people to sample, but more often than not the promotional machine is based on “the song” as a gateway into “the album.” Labels release a track and send it to all the major blogs/websites for people to share. A band posts a stream of their new single on their website and uploads the video to YouTube. Blogs will highlight a particular track or single and discuss its relationship with the album in question, but the song is the starting point – which says something when you consider that these new “elites” of cultural dialogue are the very sorts who still hold up the album as an art form.

What we have to remember is that the album as “art” – as a unified collection of song guiding the listener through a journey – has always been an accidental side effect of its primary role: the album as “commerce.” Until technology allowed the mass production of the vinyl long player (LP), the song was the only real capital in the music industry. And when the LP first arrived, most bands and artists tackled it as a commercial product – we can get people to buy 10 songs instead of just one! – than an artistic medium. It was only when folk music collided with rock in the 1960s that artists began exploring ways to use the 45-or-so minutes of a record for something more than just a collection of songs. Even then, it took years before the single was phased out as a commercial item.

But by the 1990s, the vinyl single had been relegated to a hipster novelty. The rise of the compact disc as the dominant medium gave the record industry the power it needed to finally rig the game in its favour: make the listener buy 12 songs (or more) if they want to own that one they really love from the radio. They used and abused that power for almost two decades, an artificial commercial inflation that masked the underlying decline in consumer demand for music. The great accomplishment of digital distribution is the shattering of this paradigm and, once again, returning to the consumer their power to purchase music on their own terms; heck, increasing it, really.

This is why I have little sympathy when AC/DC and Kid Rock make a strictly economic argument for avoiding iTunes. They seek to force users to buy more than they actually want, rigging the game in their commercial favour at the expense of the audience’s actual wishes. Pink Floyd, however, seems to be making an artistic argument, and that warrants a different response. Because while I’ve long outgrown my Pink Floyd phase, there’s no question that they were a band that made “albums” in the artistic sense, complete visions that do take the listener on a journey song-by-song.

But should they get to dictate that journey?

The relationship between artist and audience is almost never didactic, even in its most structured forms. When I look at a painting or sculpture, I get to decide what I look at, what angles I approach it, and what elements catch my eye. When I read a book, I have the freedom to skip ahead or move around at my leisure – even if I rarely use that freedom. Movies and television are, obviously, more linear and controlled but even then the experience is shaped and moulded by our reactions to it (to get Barthesian for a second).

Music, it seems to me, is more audience-driven than any of these. We use music as our personal soundtracks, associating it intimately with the moments of our lives be they mundane or magnificent. We make mixtapes for friends and lovers. When we have people over, we make our own playlists to last as long as the conversation does. We choose a hot new track as our phone ringtone. We race to the dance floor when our favourite track comes over the speakers. Every single one of these behaviours – common to all of us – rips apart the “integrity” of the album.

Therefore, when push comes to shove, the album only has integrity if we, as listeners, want it to. If a listener chooses to listen to Dark Side of the Moon from start-to-finish as I did back in the day, that’s great. But if they decide that they only want to listen to “Money,” should the band throw barriers in the way of doing so? Put another way: is there not artistic value to “Money” independent of Dark Side of the Moon? And even if it’s best experienced as part of the whole – a debatable proposition – does the ability to value it separately diminish the album from which it came?

Of course it doesn’t. Great albums will always be great albums, and great songs will always be great songs. Those moments where they cross over shouldn’t be discouraged; they’re opportunities for the listener to start with something small and, if they like what they hear, discover something truly wonderful. But it’s the listener’s journey, and it’s one they should get to make on their own terms.