The Lewis Klahr Experience: Sex, Drugs and Animation

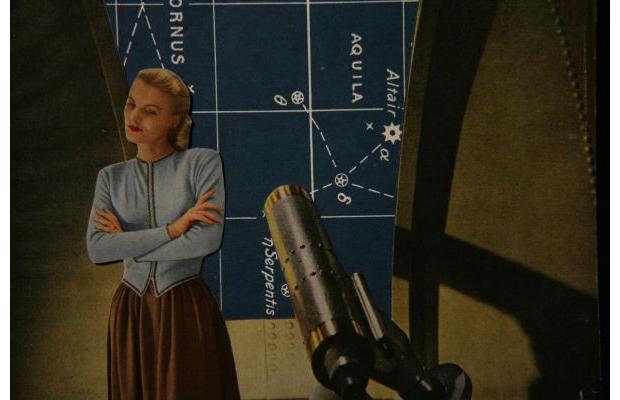

A scene from Lewis Klahr's film Altair.

When I walked down the stairs to the Segal Centre's CinemaSpace in Montreal on May 18, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. That night, rough sexual images shocked and sometimes angered me; they stabbed at my biases and rigidity. But I'm sure I'm not alone: that's just how it feels the first time you watch the work of American animator and filmmaker Lewis Klahr.

"People tell me when they watch my films, they experience long after-effects," said Klahr, who has been using collage techniques to create experimental, sometimes disturbing films since the late 1970s. In an event titled "Lewis Klahr: Hieroglyphs of Lost Time," the Segal Centre screened Engram Sepals, a series of seven short films depicting a decades-long downward journey of sex, drugs and alcohol. It pulls viewers into an eighty-one-minute orgy of substance abuse, confusion and sexual experimentation, and exposes American vices and anxieties. Shooting on 16mm film, Klahr used images cut from from magazines, comic books and '70s porn rags, as well as old Super 8 footage, to create distinctly adult animations.

Klahr, who was in attendance at the event, explained that the short stories he told in his films were really about discovery. He carefully sourced and selected each image he used in his collages and, he said, everything has a meaning; just as the real world has structure, so do the worlds he created. He emphasized that music and images need to reinforce each other for a film to work. "I wanted the emotions like in a Dionne Warwick song, combined with experimental movies," Klahr said.

The epic voyage of Engram Sepals began with the 1994 short Altair, a shifting collage of images from 1940s issues of Cosmopolitan. Behind the romantic images of well-manicured women, there was an underlying sense of doom. Klahr used blue-tinted backdrops and repeated images of cigarette cases, martini olives, cards and beds to evoke the feeling of addiction.

Altair—which is now included in the New York Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection—was the tamest of the seven movies. The following film, Engram Sepals was even more sinister: Jimmy Olsen, the freckly young photojournalist from the Superman comics, was shown lying dead on the ground. Then, in Pony Glass, Klahr manipulated Olsen's clean-cut persona by placing cut-outs of him in scenes of same-sex affairs, interspersing these with images of looming clocks and mid-century offices. Klahr, speaking after the show, admitted that experimental filmmakers often use repetition to encourage viewers' personal interpretations of images, and the looping music and recurring images in Pony Glass underlined Jimmy's identity crisis and sexual self-discovery.

As I was watching the series, my own brain started playing tricks on me, too. During Govinda, Klahr's 1999 take on a coming-of-age story, I inwardly named a woman in the film "Sarah." Listening to the Indian-influenced accompanying song and watching Sarah's loss of innocence, I felt as if the vocalist was singing, "Run, Sarah, run." As I watched her naively walk into a forest, like Eve taking a bite into the apple, I wanted to stop her. When her journey into the forest led her to drugs and group sex, I felt truly outraged. I did not like the chaos of the scenes. I wanted to put the world back in order. Who knew collage could be so emotional?

At the beginning of the second half, Klahr warned the spectators at the Segal Centre that the following material was not for everyone. And it's not. Viewers would go on to witness orgies, cut-outs of drugged-out porn stars having rough sex and, with the final piece, A Failed Cardigan Maneuver, I experienced a longing to return to the relative innocence at the beginning of the film. "I needed the courage and self-permission to go where those images could take me," Klahr said. A rake poked at the characters' anuses and scratched the surfaces of their skin; a needle was inserted into a penis; I couldn't help but cringe. "Even though you're not involved, they [images] still hurt," Klahr said. "You're feeling those things."

For days after seeing Engram Sepals, I had an urge to analyze every cut-out and make sense of my experiences. I wanted Klahr to explain his imagery so I could file it, label it, make sense of it. But Klahr's films stubbornly refuse to be classified.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—The Trotsky Revolutionizes Teen Film

—Celluloid Love Letter: Deborah Chow's The High Cost of Living

—Persian Dub

Subscribe — Follow Maisy on Twitter — Like Maisy on Facebook