Bonobo Diaries: The Ravages of Development

Originally, I planned to fly from Paris to Kinshasa on January 6. There, I would meet Sally Jewell Coxe and Michael Hurley, a husband-and-wife team who have spent a decade working in bonobo conservation. We would fly to Mbandika, where the Congo River intersects with the equator, then take a motorized dugout canoe eight days upstream to the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve. However, due to the elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we delayed our plans. Though President Kabila won, the results were disputed, and his foremost opponent, Étienne Tshisekedi, also claimed victory, having himself inaugurated at his residence. But the violence that many feared didn’t take place. Even though at least two dozen people were killed at polls or in demonstrations, and a Westerner’s car was stoned by locals blaming the election results on foreign intervention, many expected worse for a country in which at least 5.4 million people died between 1996 and 2008. As several people told me, the Congolese were sick of war.

Political instability, however, was enough to delay us. We were heading as far off the grid as one can go, and we needed to take precautions. So while we discussed new dates for our meeting in Kinshasa, I set off for Uganda and Rwanda. I had meant to visit both countries after the Congo in order to compare older conservation efforts for chimpanzees and gorillas with the new ones being initiated for bonobos.

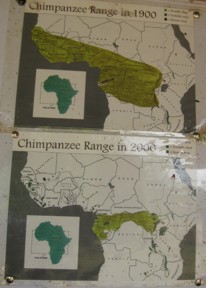

After landing in Entebbe, on the shore of Lake Victoria, I took a boat to the Ngamba Island chimpanzee sanctuary. Established in 1997, it serves as a home to orphaned chimps, often those taken from poachers hoping to sell them. The sanctuary estimates that for every young chimp captured at least a dozen adults are killed. Chimpanzees are not easy prey—they’re five to six times stronger than humans—but they, like other primates, are quickly vanishing. In fact, their habitat has dramatically diminished. Look at the photos below, taken from the bulletin board at Ngamba Island. The first is of the chimpanzee range in 1900, and the second in 2000—dramatically diminished by human encroachment and development. (The bonobo range has been accidentally included in the first and excluded in the second.)

In Uganda, the chimpanzee habitat is in the west, running along the Albertine Rift, a mountainous region of forests and lakes on the other side of which is the DR Congo. Joshua Rukundo, the sanctuary’s veterinarian, explained that even with enclaves of chimpanzee-inhabited forests remaining, the threat is less from poachers than from inbreeding. As the forests are cut into sections, chimpanzee groups become increasingly isolated. Normally, pubescent females leave and seek a new community, but the danger of crossing developments and plantations is great.

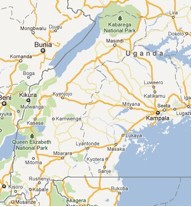

Lilly Ajarova, director of the Chimpanzee Sanctuary and Wildlife Conservation Trust, explained how she and an assistant traveled along the western border of Uganda, from the southern tip to just past Kabarega National Park.

They were trying to identify areas with chimpanzee populations and realized that many chimpanzee communities were living on privately owned land that was being deforested. As a solution, she proposed a forest corridor along the west to allow interbreeding. The means of creating this is PES, the Payment for Ecosystem Services Project, supported by the United Nations Environment Programme (maps and further info here). This involves measuring and counting trees on private land, and funding owners who maintain their forests.

PES has so far been the only way to prevent further encroachment in a country where many of the houses are made of roughly milled planks, where lucrative palm oil plantations are increasingly common, and where, above all, charcoal is used by most families for cooking. In Rukungiri, where I spent a week, people complained of a propane shortage. Charcoal, the only alternative, is made by kilning wood. What remains is light, easy to transport, and effective for slow cooking. I watched my neighbours go through a large plastic grocery bag each day—at least 15 liters—of heating water for tea and making meals. With a population of approximately thirty-two million, Uganda, not to mention the rest of Africa, must be using remarkable quantities of wood.

Here are some photos. The first is the coast of Ngamba Island sanctuary, where the forests are being allowed to recover:

The second is the neighbouring island that our boatman told me was similar to Ngamba only a few years ago. The cutting of wood for homes and charcoal has reduced it to this:

The third is a palm-oil plantation in the middle of the forests of the nearby Ssese Islands. Palm oil is used not only for cooking but for biodiesel, as well as soaps and hundreds of other items commonly found in our supermarkets (here is an article listing products). In Indonesia, such plantations are replacing primary growth rainforest and pushing the only non-African great ape, the orangutan, towards extinction. Even Borneo’s forests, once among the most pristine on the planet, are quickly being decimated.

I haven’t said much about the gorillas. Like other great apes, all subspecies are endangered, with only 280 Cross River gorillas and 790 mountain gorillas left in the wild. In both Uganda and Rwanda, a strong eco-tourist network has been built around gorillas. A visit to the gorillas requires a permit and costs $500, not including the price of transportation and a guide. Their economic value has created incentive to protect them and their habitats in impoverished countries where the citizens might otherwise be uninterested. And in Rwanda, newborn gorillas receive an annual naming ceremony just as human children do. Only in the east of the Congo, home to rebel groups that fled Rwanda after the genocide, are the gorillas in danger. Militias funding themselves with the sale of charcoal shot a family of mountain gorillas to make a point to the park rangers who were hampering their business.

But in the heart of the Congo, in the bonobo range, where there is not yet thriving eco-tourism, war slowed development, and the rainforests, some argue, are more intact as a result. However, with the growing stability, developers are looking to the rainforests. China is the largest consumer of the DRC’s exports—the top four consumers are China at 47.3 percent, Belgium at 15.4 percent, Finland at 9.6 percent, and the United States at 8.1 percent—and in exchange for minerals, the Chinese are building roads, hospitals and universities (for more information, read this 2008 BBC article and this Wikipedia page). Whereas the chimpanzee and gorilla ranges eroded in pace with development, the Congo rainforest is now being exposed to development’s full industrial capacity, and the decimation promises to be quick.

In France, two days before my flight to Uganda, I took a bicycle ride through La Forêt de Sénart and mused at what a privilege it is to have a forest next door. The West exploited nearly all of its old-growth forests so long ago that we struggle to recall what might have once existed. Now, numerous carbon-credit programs are evolving to pay developing countries to preserve the forests. In further blogs, I will discuss how carbon-credit programs are the only equitable way to lessen the impact on the global environment. We can’t ask impoverished countries to spare their massive forests so that they can absorb our carbon emissions. (You can read about the importance of African forests here.) In their eyes, their forests are a source of raw material to build their economies, and, in the case of the Congo, the minerals beneath the forests are even more promising.

Now I am in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, a city boiling with industry. In a few days, I will cross the border to Goma, in the DRC, and will fly to Kinshasa to meet Sally Jewell Coxe and Michael Hurley (bonobo.org). There, I will write more about their work to preserve both the bonobos and their valuable habitat.

Deni Y. Béchard's first novel, Vandal Love, won the Commonwealth Writers' Prize. Over the next several months, he will blog for Maisonneuve regularly from central Africa as he researches his new book. Track him online here with a satellite GPS tracker. His travel updates and reading habits are on Twitter at @denibechard.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Bonobo Diaries: Why I'm Writing a Book About the Congo

—Bonobo Diaries: A Conversation With Sue Savage-Rumbaugh

—Waste Not