Reshaping the World: James Stirling at the CCA

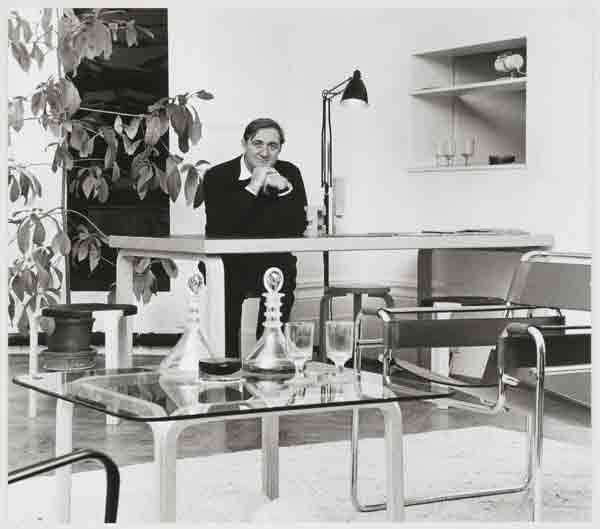

Portrait of James Stirling. Ray Williams, photographer. Gelatin silver print, 18.8 x 21.4 cm. James Stirling/Michael Wilford fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture © Ray Williams

"Frequently I awake in the morning and wonder how it is that I can be an architect and an Englishman at the same time, particularly a modern architect. Since the crystallization of the modern movement around about 1920, Britain has not produced one single masterpiece." —James Stirling, 1954.

As observers of architecture, we tend to focus on the finished form. Perhaps we imagine engineers and designers hunched over desks with pencils behind their ears, calculations running in long columns along their papers; but most of the time, we give it no thought at all.

Notes from the Archive: James Frazer Stirling invites us to look behind the scenes into the life of architect Sir James Frazer Stirling, and the legacy he left behind. The exhibit on display at the Canadian Centre for Architecture features over five hundred original drawings, models, videos and photographs from Stirling's life.

The exhibit's topic may seem tedious, but multimedia features like video and audio clips bring the archives to life in a stimulating and carefully arranged presentation. The Canadian Centre Architecture plunges visitors into Stirling's work, each exhibition room a drawer of his office desk, filled with notes and newspaper clippings.

As one of the most influential twentieth-century architects, Stirling is well known for his successful career. Born in Glasgow in 1926, he gained international acclaim from the Staatsgalerie at the Stuttgart museum in Germany to the Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Notes from the Archive presents Stirling's works in chronological order, spanning from his university thesis to the work he left unfinished when he died in 1992.

The plethora of materials on display reveal more than Stirling's process. A bird-watching notebook from Stirling's youth sits open in the first exhibition room, complete with handwritten annotations and drawings of birds. This early attention to detail is later manifested in Stirling's love for photography. Many of the photos show him wearing a camera around his neck, which he used to capture a personal encyclopaedia of potential sources and inspiration.

"He was a big man with a gentle nature," says exhibit curator Anthony Vidler, Professor and Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at the Cooper Union. Vidler remembers Stirling as one of his teachers at Cambridge, and later as a friend. Pointing to one of the many diagrams hanging on the exhibition walls, Vidler recalls how Stirling would hold a stubby pencil in his large hand and complete a detailed sketch with surprising agility.

More bibliography than archive, the exhibit breathes fresh life into Stirling's legacy. Walking into each room is like opening one of Stirling's briefcases. The notes jotted on the backs of airplane boarding passes and hotel stationary line the walls, from incomplete sketches to finished diagrams.

Conceptual sketches and axonometric projections of the University of Cambridge provide a context for the models of his finished works on exhibit. From a bird's eye view, visitors peer down at the Leicester University Engineering building (1959-63), the History Faculty building at Cambridge University (1964-67) and his competition entry for the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1989.

Despite critics' many attempts to categorize Stirling's work, he refused to be associated with any label. His eclectic style often challenged the modernist movement, which he called "boring, banal and barren" in an address at the International Congress of Architecture.

His struggle against modernist styles came to a controversial climax during the rehousing development in Preston, England (1953-1961). The low-rise terrace housing aimed to address the destructive tendencies of suburban sprawl—in Stirling's eyes, modernism had paved over the open-air street life necessary for the vitality of the working-class spirit. He aimed to replace the isolated tower blocks with a housing development that focused on community.

The project drew many supporters and dissidents—it earned Stirling the Good Housing Competition prize, and the Daily Mail responded by running a critical piece entitled "Frankly, do you think this is worth a prize?"

A series of large, black and white photographs mounted at Notes from the Archive suggest Stirling's intent with the Preston development. The photos, taken by Stirling, show children running and playing on the ramps and streets of the redesigned working village, their feet dangling as they sit on the edges of brick walls. Fathers with briefcases return home from work and mothers walk on the sidewalks carrying grocery bags. His intent, however disputed, seems clear: to create a working village that is neither utopia nor slum, but a space of compromise suited to daily life.

Sifting through the old notes and sketches of an architect may seem tedious, but the Canadian Centre for Architecture presents Stirling's archives in a surprisingly intriguing manner. Notes from the Archive: James Frazer Stirling provides a contextual backdrop to the life and work of a man who literally reshaped the world.

Notes from the Archive: James Frazer Stirling is on display at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (1920 Baile St.) in Montreal until Oct 14. Be sure to also visit Very Big Library on view in the museum's Octagonal Gallery until September 9.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—The Political Legacy of Argentina's Graffiti

—New Remedies: Imperfect health at the CCA

—Journeys at the CCA: The Architecture of Migration