Grass and Butterflies: Van Gogh at the National Gallery

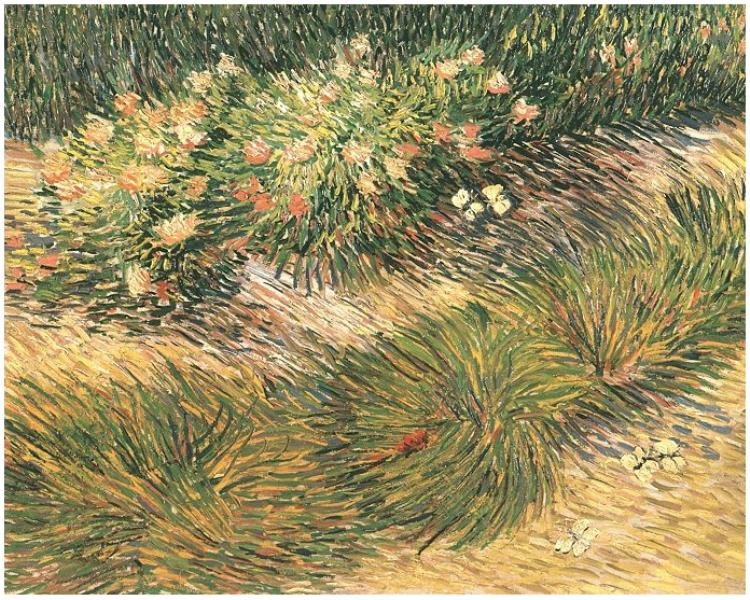

Van Gogh's Grass and Butterflies.

Van Gogh was given permission to paint in the overgrown garden behind the asylum where he lived in southern France. Had he thrown himself into the open fields of wheat and wild irises then, he would likely have been nabbed and shut away. Instead, he threw himself into painting those fields. He knelt down over a flower, plucked a single blade of grass.

Van Gogh's intimacy with nature—a side of the painter often eclipsed by his mythic status—inspired this summer's feature exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, on now until September 3. Guest curator Cornelia Homburg and the Gallery's associate curator Anabelle Kienle Ponka want you to look at Van Gogh as you have never seen him before: up close.

Just inside the exhibition space, I was struck by a five-panel alcove, covered floor-to-ceiling with a section from Grass and Butterflies. Blown up beyond recognition, the excited, willowy gestures of paint jump to the fore. Huge, urgent brush strokes drew me in immediately. I stepped into that field in southern France and was embraced by the tall grass. I saw Van Gogh do with his brush what he could not do when shut away. He sploshed paint as one would frolic in nature, the grass swaying, almost, in the wake of each stroke.

It was pleasantly disarming for the National Gallery of Canada to beckon me this way. Van Gogh: Up Close seems to go against what I have been told to do in galleries and museums, countless times, since I was little: Stay back! Don't touch! Don't get too close! Though gallery attendants are still at hand, it is clear we are being welcomed to lean in and look carefully, as did Van Gogh in painting these works.

By strictly showing landscapes and still-lifes from the artis''s French period, this exhibition is not trying to be a retrospective, or even a comprehensive look at Van Gogh. I found it rather episodic, actually. Works are grouped by what they depict—"Blades of Grass," "High Horizons," "Tree Trunks and Undergrowth"—each frame a window onto the French countryside, but also onto the pinnacle of Van Gogh's life. His last four years are known as his most productive, innovative and—thanks to the storied ear incident—volatile.

Van Gogh: Up Close shows a more contemplative side of The Tortured Artist. He "pictures nature as though lying in it," says Homburg as she tours the exhibition. The close-ups and high horizon lines certainly suggest a crouching or kneeling artist. After a history of religious struggle—Van Gogh's father was a minister—here is the artist at peace in an open field, on his knees. In his many eloquent letters to his brother Theo, he writes extensively of meditating on "a single blade of grass," a reference to the practice of Japanese Buddhist monks, whom Van Gogh so admired.

At the time, the centuries-old tradition of Japanese woodblock printing burst onto the trendy Paris art scene. Van Gogh, like many others, was an avid collector of the brightly coloured prints. He decorated his room with them, whereever he was living. This kept nature close, even in dingy Paris.

To help demystify Van Gogh's influences, the exhibition includes over a dozen of these mid-nineteenth-century prints, borrowed from the Royal Ontario Museum, along with European prints and drawings of nature from the National Gallery of Canada's own collection. This way, his style stands out as more than just eccentric. The almost scientific European studies of nature and the bright Japanese prints highlight Van Gogh's diligent study of, and contribution to, artistic tradition.

Almond Blossom, for instance, is similar to the Japanese style in subject matter, perspective and technique. While most paintings on display feature close-ups of low-lying subjects, like flowers, grass, and wheat, this one suddenly flips the gaze upwards. It's a bit disorienting since there isn't even a horizon line. Yet each sun-kissed almond blossom is set, like a diamond, against the bluest sky. The painting is so fresh I swear it would still be wet to touch.

Touring the exhibition, Homburg lingers on Almond Blossom, which is set apart, on the back wall of the last room. She recalls how she coaxed it from its keepers. Normally, it stays at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Never before had it been seen in North America.

"'If there ever was an exhibition to show this painting, this would be it,'" she remembers museum staff telling her, finally. At that moment, she thought, "Now we're getting somewhere!"

It was Homburg's particular focus—close-ups of nature—that pried such key works from museums and private owners, says Kienle Ponka, with a smile to her co-curator. It all started with a phone call between the former colleagues, five years ago, when Kienle Ponka first assumed responsibility of the European and American Art collection at the National Gallery of Canada.

"Did you know you have this magnificent painting, and it has this special history," she remembers Homburg starting. "But also there's something about it that has never been looked at in the scholarship."

The painting was Iris, which the National Gallery of Canada acquired from the Netherlands to help repay debts after WWII. Just as lively as any portrait, it is easy to imagine Van Gogh kneeling over this particular flower.

Back in southern France, every year, Van Gogh draws thousands of pilgrims to his gravesite, where he and his beloved brother Theo are buried side by side. Van Gogh died without ever knowing of this tremendous acclaim. Few took notice of him while alive, despite his brother's considerable influence in Paris. His work and personality were just too glaring, like staring at the sun. But take another look. Up close, with layers of myth stripped away, Van Gogh may even surprise you.

Van Gogh: Up Close continues at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa until September 3.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—The Political Legacy of Argentina's Graffiti

—New Remedies: Imperfect health at the CCA

—Journeys at the CCA: The Architecture of Migration