The Boss in 2012: Reflections on Five Bruce Springsteen Shows

Sports Arena, Los Angeles, Night Two – April 27

The tickets say “7:30 p.m.” but no one’s expecting the band to start then. You always allow some grace time for people to get to the venue, especially in a city like Los Angeles with a reputation for late-arriving audiences.

And yet, strangely, the chorus of “Bruuuuuuuuce” starts up about 7:20 or so, and there he is: not yet in his show clothes, flanked by a good dozen or so other people, taking a walk around the stage. He calls for his acoustic guitar—a necessary prop—and poses for a few photos with the group. Sensing that we’re a bit confused in the crowd, Bruce asks the sound guy to turn on the mic so he can explain.

“This is how I entertain my relatives every Friday and Saturday night,” he says with a smirk. “That’s my Uncle Donnie, Aunt May, my little cousin Julie…you gotta put up with me and my relatives too!”

A couple minutes later, his family members all leave the stage, with Bruce trailing behind, casually strumming his guitar. But just as he’s about to walk away, I catch a wry smirk cross his face. He gestures to the sound guy again, makes a turn, and heads straight for the mic.

“Princess cards she sends me with her regards

Barroom eyes shine vacancy, to see her you gotta look hard

I was wounded deep in battle, I stand stuffed like some soldier undaunted

To her Cheshire smile, I’ll stand on file. She’s all I ever wanted”

Most of the sold-out crowd that, an hour later, will rock out to classics like “No Surrender,” “Badlands” and “Born to Run” have no idea that this is even happening. While the show’s general admission floor has filled up quickly—keeners like me who took part in the afternoon’s lottery to get into the front “pit” section—the vast majority of the Sports Arena’s seats are empty. There are, at most, a handful of people in each section. This performance of “For You,” one of Springsteen’s oldest songs, is just for us: the devoted, the converted.

And it’s magical: the gawky, wordy innocence of Springsteen’s early writing elevated to new heights by the weight of the years in the man’s voice, and the sense that he did, indeed, come here just for us.

“We’ll see you in a little while,” Springsteen says when the song’s over, as the exhilarated audience tries it’s damnedest to fill the venue’s empty spaces with jubilant thanks.

I’d later find out that the last time he did this sort of thing was in 2003 in Paris. He would do it again for a five-song (!!!) pre-show in Helsinki, his final 2012 show in Europe. But the point is: this was rare. This was something special. This was not normal.

Not that there’s anything normal about Bruce Springsteen.

* * * * *

My first Springsteen concert, and my only one prior to this year, was in April 2009 in Los Angeles. There with my brother, general admission tickets in hand, I was astounded by the devotion of my fellow floor-goers at the show. Many had seen Bruce three or four times that year already (he just started the tour in March). They all had war stories from tours past, fevered tales of ‘75, ‘78, ‘81, ‘84, ‘99…the sort of lore which, as I dove into Springsteen fandom, I came to know quite well.

That first show was a remarkable evening, and I had no doubt in my mind that when Springsteen toured again, I’d be there. But never in my wildest thoughts did I expect that I’d be there six times in one year.

I have become one of “those guys.”

Admittedly, it’s not like I planned this; it just sort of happened. The first North American leg of the Wrecking Ball tour had dates in Boston and Los Angeles that coincided with other trips I was already planning (a music conference in New York and the Coachella Music Festival), so those just made sense. And when Springsteen added a second date in Los Angeles after the first show sold out in minutes, well, that made sense too (since I was staying with my cousin, I didn’t have accommodation costs to worry about).

An August show in Moncton was a no-brainer, since it’s right in my backyard, and when shows at Fenway Park were announced, my friend Adam and I couldn’t pass up the chance to mesh together a baseball mecca with another Bruce show (especially once we managed to get pit tickets). And since we got to Boston a bit early, why not hit the streets to find cheap tickets to the first Fenway show as well?

Six perfectly logical decisions that when put together seem completely ridiculous. The opportunity cost of spending so much time/energy/cash on a single artist is huge; can any performer possibly be worth it?

This essay is my attempt to answer that question, even if only to myself.

Spoiler alert: I think the answer is yes.

* * * * *

TD Garden, Boston – March 26

“Could these seats be any further back?” asks the husband of his wife as they entered the second-last row of the upper bowl.

“Yes, actually” replies the smart-ass Canadian from the last row of the upper bowl.

That gets a good laugh from everyone, and for the rest of the show my fellow grad students and I get along famously with the Boston couple in front of us. It’s the husband’s 20-somethingth show—a number which seemed crazy to me at the time (obviously, less so now)—and he’s more than happy to talk about all things Springsteen. He tells us that his wife’s favourite song is “Land of Hope And Dreams,” and that never ceases to make her tear up, though he wishes Bruce had left it unrecorded as a special live treat for fans. And his explains that his teenage son plays the saxophone because of Clarence Clemons, but isn’t at the show tonight because he’s not sure he can bring himself to see the E Street Band without its Big Man.

Clemons isn’t the first E Streeter to move onto the great gig in the sky—organist Danny Federici passed away in 2008, during the Magic tour—but his absence is particularly profound. His saxophone was a defining element of many of the band’s most beloved songs, but even more than that, he was Springsteen’s foil, the big-hearted, soft-spoken counterpoint to Bruce’s boisterous enthusiasm. Born to Run’s “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out,” a song outlining the band’s origin myth, positions Clemons’ joining the band as the transformative moment in its upward trajectory, and it’s a point of view that’s hard to argue with.

Rather than ask one person to carry all that weight, Springsteen has elected to tour with an entire horn section, the first time he’s done so since the Tunnel of Love Express tour in 1988. In interviews, he and the band have claimed they wanted to take the opportunity to try something different, and there’s no question that the horns have been a highlight of the Wrecking Ball tour.

I have a slightly different theory, though: that Bruce also wanted to provide cover to Jake Clemons.

Jake, Clarence’s nephew, is not a young man (he’s 36), nor an inexperienced one (he’s played with everyone from Will Smith to Eddie Vedder). And there’s certainly something endearing about choosing a family name for a new saxophonist, since there’s always been something family-like about the E Street Band even when it was estranged. But while Bruce clearly felt that Jake warranted a spot with his band, he didn’t give him the sole spotlight. It’s almost as if he was hedging his bets in case the crowd didn’t respond to Jake – or if Jake struggled to fill his uncle’s gigantic shoes.

Three songs into the Boston show, after opening with two Wrecking Ball highlights, Bruce yells out “ONE, TWO!” and Max Weinberg’s drum fill comes roaring through the PA. We know immediately what’s coming: “Badlands,” with one of the most iconic sax solos in Springsteen’s discography (fun fact: it was added to the song in the studio at the last minute), and I’m immediately curious whether Springsteen gives the moment to Jake or the more experienced saxophonist in his horn section, Ed Manion.

It’s Jake. And he simply nails it.

From that point on—and consistent throughout all the shows I’ve been to—the crowd is totally behind Jake. What’s more, he gets all the most famous solos : “Born to Run,” “Dancing in the Dark,” “Thunder Road”; Ed really only gets the spotlight on “Waiting on a Sunny Day.” The roars that Jake gets from the crowd are, time and time again, some of the biggest pops of the night. And often, after he finishes a solo, he looks up and points to the sky, as if acknowledging the man whose horn belted that solo in the first place.

I remember the moment I learned Clarence had passed away: I was at a dinner party, and I was shaken up enough by the news that friends actually commented on how I seemed more distant than usual. I wondered whether I’d ever get to see the E Street Band again, whether it could exist without The Big Man.

Bruce never doubted that it could. As he put it at Clemons’ funeral, “Clarence doesn’t leave the E Street Band when he dies. He leaves when we die.”

* * * * *

Each tour, Springsteen generally picks one song during which to illuminate some of the show’s themes in a lengthy, always entertaining speech. On the first E Street Band reunion tour, it was “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out.” For Magic, it was “Living in the Future.” During the Working on a Dream tour, it was that album’s title track.

Given how thematically strong his latest album is (I wrote about Wrecking Ball in detail back in March) you’d expect one of those songs to get “the speech,” but Bruce has instead chosen a repurposed, revelatory rendition of The Rising’s “My City of Ruins,” elevated to new heights by the horn section. While he also tends to intro Wrecking Ball’s “Jack of All Trades” and “We Are Alive” with speeches, it’s during “Ruins” that he pauses the show for several minutes, introduces the band, and outlines his agenda.

And, interestingly, it’s not as political or social as most of Wrecking Ball seems. Instead, the speech hits at one of the album’s other interesting elements: a dialogue between the past and the present, and a reflection of what’s been lost and gained as we move through time. It concludes with Springsteen asking “Are we missing anybody tonight?” encouraging the crowd to cheer loudly for fallen E Streeters Clemons and Federici, after which Springsteen reassures, “Well if you’re here, and we’re here, then they’re here.”

Like Wrecking Ball itself, the tour seems deeply invested in the past, with what—and who—has come before. But unlike so many of his contemporaries content to perform their back catalogues as museum pieces, Springsteen is committed to the idea of a living past. He digs up old favourites, obscure rarities and playful covers, meshing them alongside his current material with such grace that they become inseparable. His shows refuse to reduce his past to a caricature, or an easily consumed greatest hit product: they show Springsteen in all his complications and contradictions. The point being: you can’t let your past define you, but it sure as hell shapes you. And you better reckon with that.

Take the song “Wrecking Ball” as an example: on the surface, it’s a simple anthem about a sports stadium, but Springsteen uses that foundation as a reflection on the passage of time, on the weight of a live well lived and the ghosts we can’t shake. Its call, to “Bring on your wrecking ball,” is not a call for resurrection. It’s sound is final: an acceptance of the end.

That end is coming for all of us. For the E Street Band, two members down, that end may not be that far away.

* * * * *

Sports Arena, Los Angeles, Night One – April 26

When you end up seeing Bruce six times in one year, you quickly become a “setlist watcher” – for better, and for worse.

Most bands really aren’t worth watching setlists for. When Tom Petty came through Halifax a few months ago, for example, his song selection was hardly a surprise: he’d been playing nearly the exact same show, start-to-finish, all year. But Bruce is different. His shows do have an arc that he’s working with, and there are many sections that repeat night after night on a tour, but he allows himself all sorts of opportunities to change things up.

The upside of this is that even the minor changes are exciting. Seventeen of the 25 songs at my second Springsteen show this year are the same as the first one; generally, Bruce keeps his shows more consistent early in the tour, then starts really mixing things up as the year moves along. But each of those changes is something exciting.

For example, the tour debut—and yes, “tour debuts” are also a thing, as if the idea that you’re seeing something before other Springsteen fans carries weight—of “Something in the Night,” leading straight into “Candy’s Room” like it does on Darkness on the Edge of Town, sends me into a minor tizzy of excitement. “The E Street Shuffle” takes the “old, old song” slot this show, and it is every bit as great as it was on Jimmy Fallon back in March.

But for me, the highlight is getting to hear one of my all-time favourite songs, one I’ve yet to see live: “The Ties That Bind.”

Springsteen’s discography is rife with anthems of masculine salvation: songs of broken men trying to find broken women that they can heal. As a gender-conscious music geek, sometimes this theme can get a bit troubling (“Fire,” which is borderline date rape-y in its original form, is perhaps the worst offender). But more often than not, Springsteen pairs this sentiment with enough self-criticism on his protagonists’ part—with a healthy dose of romanticism—that it works.

And it rarely works better than The River’s “The Ties That Bind,” perhaps the most adult love song he’d written to that point. In it, he sings “You walk cool, but darlin’, can you walk the line? / And face the ties that bind.”

One of those reasons that those lines have resonated with me is that there’s nothing cool about Bruce Springsteen – at least, not cool in a millennial sense. Growing up in the era of grunge and indie rock, cool was about not caring, about demonstrating an emotional distance from what was right in front of you. And, accordingly, I was decidedly uncool. While I’ve never been the most emotional person—my family lineage, and gender, granted me a certain distance that I still carry with me—I’ve always been a very excitable person, especially about cultural things. When I’ve found something I’m passionate about, I get really passionate: I have to learn everything about it, I have to tell people about it, I have to share it.

I’ve long wondered why it was that Bruce Springsteen, above nearly every other artist from before my own time, resonated with me. Partly, it’s that he became relevant again when I was at my most exploratory, musically: in the early 2000s, during The Rising era. But it’s also that the entire core of Springsteen’s work is about caring: about finding life worth living, whether your circumstances are joyous or hard. There’s humour in his work, but none of the irony with which I cope with so much of the modern world. In Springsteenland, things matter: what people do, what they say, how they live.

So I’ve kind of always felt like “The Ties That Bind” was speaking to me, telling me to stop worrying about the pretenses of cool and follow my passions, to wherever their road might take me.

I’m still not sure I always do that. But standing in a Springsteen crowd, I feel like I’m doing it better than not.

* * * * *

“Bruce Springsteen: Can his shows be too long?”

That’s the question the Toronto Star asked this week, as the paper’s music writer Ben Rayner interviewed a number of Toronto music people about the idea of long shows. The consensus seemed to come out as: “We’d never do it, and it’s not for everyone, but if you’re Bruce, why not?”

Springsteen has always been known for long concerts, though his legend outpaced reality in that respect: statements about The Boss playing four-hour shows have circulated in the press for years, when he only just crossed the 240-minute mark for the first time in Helsinki, Finland in July. But even when he was touring Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River, his shows were two sets long, and pushed towards and sometimes past the three-hour mark.

This year, Springsteen is playing the longest shows of his life. When the tour started in North America, you were pretty much guaranteed a three-hour show. Then in Europe, the shows began to creep longer and longer, including a few that flirted with (or in the case of Helsinki, broke) Springsteen’s own record. Now, back in North America, shows are topping out at 3.5 hours — still incredibly impressive for a band whose members are all in their sixties, and whose frontman never stops moving during the entire show.

There’s something about that rock and roll excess that’s incredibly compelling. As Rayner puts it, it reflects a “dogged commitment to giving the people what they want.”

But what people, exactly?

It’s worth remembering that what Springsteen does in concert comes with its downsides, the largest being that it risks alienating casual fans. Springsteen always plays a healthy handful of his hits, but he doesn’t structure his show around them either. His shows are filled with beloved album tracks, and covers that range from iconic to little-known, and he’ll often dive exceptionally deep and play non-album songs from collections like Tracks or The Promise – in other words, songs that even a Springsteen fan with most of his albums might never have heard.

Oh, and he also still structures his shows around new material (unless it sucks, like on the Working on a Dream tour) when most of his contemporaries are more than happy to present their legacy as more-or-less complete.

Perhaps this is one small hint as to why Springsteen has stayed culturally interesting in the 2000s: though he comes from an era of mass broadcast, and a generation of musicians who today are more than happy to aim for some sort of mass audience experience (how many deep cuts do the Stones or AC/DC bring out on tour?), Springsteen has always been narrowcast. He expects more of his audience than a simple awareness of his biggest songs: concertgoers must be prepared for a journey through his work in a detailed, comprehensive fashion. In other words, he plays to the fans first and expects everyone else to come along for the ride.

The one time that he played broader, of course, was Born in the USA – his one mega-hit album, and probably the single reason that he’s able to play stadium shows in big North American cities today instead of sticking just to arenas. (In Europe, he can play huge shows anywhere, but his fascinating appeal over there is a whole other essay.) But most of Springsteen’s career, both live and on the record, is much more knotty, twisted, and the thrill as a fan is seeing him try and bring all those different corners together over the course of an epic concert.

So when news reports come out about “slow” sales for the Moncton show—20-30,000 instead of the 50,000+ for shows like U2, AC/DC and the Stones—factors like ticket price and the Sunday night timeslot certainly play a part, but I’d argue the biggest factor is just that Springsteen isn’t the type of band who can, or should, pull in sales that high.

Unlike his baby boomer contemporaries still trying to play to everyone, Springsteen is far more of a 21st century man: play to the converted, and play so fucking good that others want to join in.

They just better be ready to keep up.

* * * * *

Fenway Park, Boston – August 14 and 15

They say that if you have the choice on a two-night Springsteen stand, go with night two.

Night one, the story goes, tends to be more like his standard show on each tour, with not a lot of variation. But, knowing that he’ll have a number of fans at both shows, all bets are off on night two.

In Los Angeles, this was only sort of the case: out of 25 songs, only about seven changed night over night, though admittedly some of these changes were incredibly exciting and, pound for pound, night two was the better show. With the Fenway shows, he was playing a city he’d already played once before in 2012, so the thinking among fans was that there was some real potential for surprises.

Night one isn’t originally on the agenda, but when Adam and I arrived in Boston at a decent time on Tuesday evening, we decide to trek to Fenway and see what was up for grabs. When we find $50 tickets, from a couple just looking to make some of their money back, it’s a no-brainer. We don’t have the best view, but it’s more than alright to take in some of the show’s best moments: a rare “Drive All Night,” a thrilling “Atlantic City,” a blistering “Because the Night” and some great garage rock in “Dirty Water” and “Boom Boom.” But there isn’t a huge amount of shakeup from the standard Wrecking Ball arc.

But from note one the next night, something is different.

Bruce enters with only pianist Roy Bittan in tow. “We used to start like this back in the 70s, but we haven’t done it in the States in a long time. So feel free to sing along.” And so he launches into “Thunder Road,” just him and the piano, like how he used to open shows on the Born to Run tour. When he reaches the line “So you’re scared and we’re thinking we ain’t that yooooong anymore,” he stops and lets the crowd sing, letting the chorus also continue the follow-up line: “show a little faith, there’s magic in the night.”

It’s a clarion call for an aging performer and his audience: an acknowledgement that what’s being done is hardly new or fresh, but an ask to hold true to faith: that rock and roll can still be magical.

And so it is.

“We’re going to start with the hits….the summertime hits,” The Boss exclaims, as “Hungry Heart” starts the show proper, the crowd singing the first verse as it’s always been done live. But then Springsteen calls an audible—the term used to describe when he changes the setlist on the fly—and launches into another “summer song,” The River’s “Sherry Darling.” From there, it’s onto a cover of “Summertime Blues,” then possibly the best song he’s written in the past decade, “Girls in Their Summer Clothes.”

None of these last three songs are on the written setlist.

After playing a few Wrecking Ball tour standards (the title track, “Death to My Hometown” and “My City of Ruins”), Springsteen stops the show and walks to the crowd. “What do we got down here tonight?” he asks. “We’re gonna see what these folks wanna hear.” Springsteen is known for picking out signs from the crowd to play, but every now and then he’ll actually just start collecting them and see what happens.

“Give me that one. Ooo, that’s a hard one. Yep, bring that up. I don’t know if we know that one. Oh that one – we might be able to play that one, bring it up.”

Thus begins an incredible, almost unbelievable section of an incredible show. It starts, as Bruce puts it, “the weirdest one”: a cover of Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” and Springsteen isn’t sure if the E Street Band has ever played it before. (Internet later finds out that it has, once before, in 1976.) Once the players figure out the key, they nail it. Then comes one of Springsteen’s oldest songs, “Does this Bus Stop at 82nd Street?” then an even older one, “Thundercrack,” which never made The Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle but which used to close the band’s shows in the early 1970s. Then he pulls out a sign for “Frankie,” a beloved unreleased song that failed to fit on three different albums of his. During the song, which is slow and swoon worthy in its performance, he explains that he wrote the song on his farm in the late 70s, with fireflies all around, and asks the crowd to pull out their “fireflies.” A sea of cell phone lights fills the ballpark.

But then comes the jawdropper. Back in 1978—perhaps Springsteen’s most famed tour—the Darkness track “Prove it All Night” was a show highlight, and performed much different than it’s been played ever since. It began with this slow, drawn out piano intro, into which Springsteen added this desperate, wailing guitar solo. The whole thing ended up about eight or 10 minutes, and video footage from the time has only elevated its reputation. As early as this year, Springsteen was dismissing fan requests to play the song that way again, saying it was just a style choice they made at the time. But then, over in Europe, suddenly he busted it out again – not often, but at sporadic shows.

So when he places that sign on the stage at Fenway that said “Prove It 78,” the next nine minutes are a blur: blistering, heart-wrenching, soul-stirring. When it couldn’t get any rawer, Bruce lets Lil’ Stevie take a solo, and his garage rock ugliness has never sounded more magnificent.

Show a little faith, he sings. Prove it all night, he sings.

Maybe that’s the Springsteen live experience in a nutshell: an incredible connection between song and performance, between characters living in flight-or-fight moments and a band who proclaims that, in this moment, anything is possible.

And more often than not, you believe.

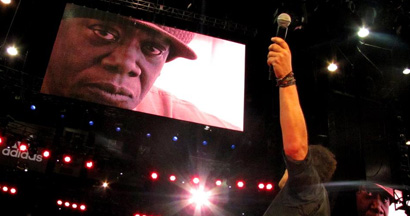

(All photos taken by Ryan McNutt at the Los Angeles Sports Arena and Fenway Park.)

From McNutt Against the Music. Follow McNutt on Twitter.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Arcade Fire, Tune-Yards and Growing Up

—9/11, New York Music and Cultural Memory

—Halifax Pop Explosion 2011 in Pictures