Idle No More, Canada's First Nations and the British Crown

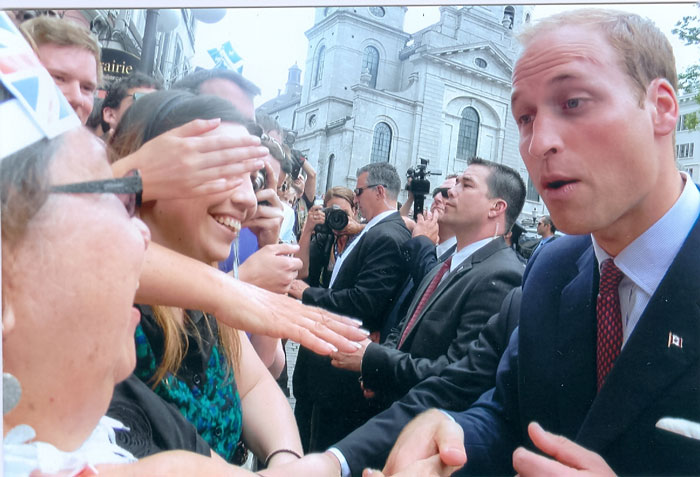

Marlene Etapp Dixon meets Prince William. Photo courtesy of the Etapp Dixon family.

In July 2011, Marlene Etapp Dixon drove for seven hours and then got up at dawn, sitting on the cobblestones of Quebec City near two francophone girls and a student from Vermont who had come with her mom. Cops kept protesters out of sight, but Etapp Dixon and her daughters and granddaughter could still hear them chanting down the street: "Fini la monarchie!" Finally, in mid-afternoon, they were up with everyone else, packed against the metal barricades, stretching out their hands and taking photos. That was Etapp Dixon's moment: Prince William walked past and grasped her hand, asking where she was from.

She explained about Waswanipi, Quebec. He raised his eyebrows and leaned in a bit, their hands still joined. "I told him, 'My people say hello to you, the Cree nation,'" Etapp Dixon told me a few minutes later when I interviewed her, a warm sixty-one-year-old wearing glasses and a cardboard Union Jack headpiece. In response, Will said he planned to visit another aboriginal community on his tour of Canada. "I said, 'God bless you,'" Etapp Dixon told me.

As Idle No More gains steam, its detractors have repeatedly insisted that, contrary to some of the movement's claims, the Queen is just a figurehead in Canada. But maybe that's just a matter of perspective. I called Etapp Dixon last week at her home in Waswanipi, an eight-hour drive north of Ottawa, where she's a social worker and now a manager at the local health agency. After a big storm there last week, her satellite went out, and, anyway, she hadn't really been following the Idle No More movement before that, she said. Was there an update? I told her that, last I heard, Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence was still insisting on a substantive meeting with both Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Governor General David Johnston. So, Etapp Dixon asked, did the Governor General go?

Pundits have been dismissive of Spence's request to meet with the Queen's representative. Spence is out of touch, clueless, "just wrong," wrote John Ibbitson in the Globe and Mail. "Native romantics dream of a king who will never come." But when the future king was here, Etapp Dixon thought he seemed nice, respectful, well-informed. He didn't even use the word "native," which Etapp Dixon uses herself. "What was the word he used—aboriginals? Aboriginal?" she said. "Just the way he said it: aboriginal. 'I know you're aboriginal people, I know.' The way he said it."

Etapp Dixon and her family are royal-watchers. She doesn't follow other celebrities, she said, but she reads a lot about the Queen and her offspring, buying books and learning about their history. Some family members were in Sudbury in 1991 when Charles and Diana came through with a young Will and Harry. "I grew to love them," Etapp Dixon said. When Diana died, she felt terrible for the little boys. She watched as "the third party" came on the scene, she said on the phone, lowering her voice, but really, she continued, those things have to come out eventually.

Talking to her in Quebec City, the prince might have been a little nervous or surprised, said Etapp Dixon, who is fluent in English but speaks with a slight accent and sometimes searches for words. William appeared especially taken aback when she invoked God's name. "It was his body language. He just, you know, popped his eyes, kind of," she said. "He was just surprised that I said that, I think. And after, I said, 'Maybe I shouldn't have said that.' I could've been the first person to tell him 'God bless you,' you know?" She chuckled. Etapp Dixon isn't Christian exactly, "just mixed," she said. "But I just say God bless to people, even in our language, in Cree, you know ... We say 'Creator.' Like the whole Jishmando Jikashiweamuk. That's how we say it. Creator bless you, or Creator acknowledge you, or bless you."

J.R. Miller, a University of Saskatchewan historian, wrote in the Ottawa Citizen this week that treaty ceremonies in the 1700s and 1800s turned First Nations and the Crown into kin. According to the customs of Cree and many other societies living here then, exchanging speeches and gifts made their people and Europeans family, and their children after them. According to tradition, the English monarch became a loving parent to the whole brood.

Etapp Dixon's family was originally from Mistissini, 400 kilometres northwest of Quebec City in the huge James Bay woods. In the early 1950s, in a deal with Indian Affairs, her father agreed to move south to live and work beside railroad tracks in rural Quebec. The family of 13 moved many times after that to different towns, and, at age eight or nine, Etapp Dixon was taken with her siblings to Shingwauk residential school, then to one in Brantford with Mohawk children, and later to others. They returned in the summer speaking toddler-level Cree, though Etapp Dixon's mother "had a lot of patience" and would try to reteach them every year. Etapp Dixon was on her own by fifteen and never really knew her parents until years later, she said. Both parents died before they ever went back to Mistissini, and Etapp Dixon married a man from Waswanipi, moved there and learned to clean animals: he was a trapper, she said, who "never went to school, so he was a good man." She graduated from Laurentian University.

When I asked her why she started liking the royal family, she said she got to know them at residential school. "We had to sing O Canada and see the picture of Queen Elizabeth," she recalled. She no longer sings, and doesn't remember the words to O Canada (though she stands respectfully in public during the anthem), but she never lost her warmth for the Windsors, she said. "My father always taught us to respect people," she said. "When I grew up, he always said be kind to people, whoever you meet, and to respect everybody. All races, to respect them, not make fun of them."

Her friends in Waswanipi like the royals too. She was so lucky to meet William, they said; some of them drove to Ottawa to see him and Kate. Etapp Dixon's late friend Johnny Yesno, an Ojibway actor and leader, once showed her an old picture of himself with the Queen when several First Nations people went to England to perform for her. Yesno, who got his name when he could only say "yes" and "no" to an Indian Affairs official, considered it a huge honour.

So, unlike about half of Canadians, Etapp Dixon doesn't want to break ties with the monarchy. "It's been around for many years. What happens when it stops?" she said. "I'd like to know more about the role of Queen Elizabeth—the role? The decisions," she added, searching for the right words. "I'd like to know more about her."

Chief Spence has written to Buckingham Palace, asking the Queen to send someone to meet with her in Ottawa, saying this relationship needs to be peeled back, reset. What her critics didn't seem to know was whether she was being intentionally provocative, or whether she truly didn't understand the Canadian political system—or whether, in fact, the "constitutional" part of our monarchy has just simply never existed.

In Quebec City, Etapp Dixon told me she was happy to see William happy after watching him grow up since that time he was in Sudbury. "It was so nice to see Will, married, with a good wife, a beautiful wife," she said. She'll celebrate when his child is born this summer. And the next time he visits Canada, she, or her daughters or granddaughter, will probably drive to see him.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org: