New Music Reads: Springsteen, Young, Byrne and More

Peter Ames Carlin – Bruce

It’s pretty ridiculous that Bruce Springsteen is about to enter his fifth decade in rock music and only now is he getting a biography that feels close to definitive.

A definitive third-party biography has to combine insight — often provided by original interviews or access to the artist or people close to him/her — and analysis, in equally convincing measure. (Most of the biographies below struggle with this balance.) There’s no shortage of solid analytical texts on Springsteen, but his tight-lipped nature means that many of them lack intimacy. On the flip side, the most detailed and insightful Springsteen biographies to date, Dave Marsh’s Born to Run and Glory Days (combined in one book as Two Hearts), are terribly written and lack any critical distance. (Pro tip: When you have to spend the intro to every subsequent edition explaining why your book isn’t a hagiography… it’s probably a hagiography.)

Carlin, who’s written well-received books about Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney, manages to bridge the divide and come closer to anyone yet at writing the Springsteen book. (And maybe the best we’ll ever get, since The Boss seems unlikely to pen an autobiography.) The book is based on interviews with pretty much everyone associated with Springsteen, including the last-ever interview with Clarence Clemons mere weeks before his death. While not overbearing, these quotes add an extra heft to the familiar stories that fill up a Springsteen book. Just as important, though, is the fact that Carlin’s take on Bruce doesn’t pull punches: he never shies away from showing how the same stubborn determination that makes Springsteen a compelling rock artist and songwriter has also strained many of his relationships, professionally and personally.

My one criticism is that the most recent decade of Springsteen’s career, from The Rising to present day, feels shortchanged. Alas, this is the challenge of writing a biography rather than a critical text: narrative often wins out over analysis. After the “comeback” is complete, with the E Street Band’s 1999-2000 reunion tour and the acclaim for The Rising, the Springsteen “story” understandably loses steam, which is a shame because I would have loved to have learned more about the background to some of his often-great 2000s material (Magic, Wrecking Ball, Seger Sessions). But if Bruce is the best Springsteen biography we’re going to get, I’m pretty ok with that.

Neil Young – Waging Heavy Peace

Unlike Springsteen, Neil Young’s already has a definitive biography: Jimmy McDonough’s Shakey (2003), based on hundreds of interviews including more than 50 hours with Young alone. So if you were to wonder what Waging Heavy Peace, Young’s new autobiography, could possibly add to that well… not much.

But that’s not to say that Waging Heavy Peace isn’t a worthwhile read. It’s just not the sort of book that’s going to offer much insight into what happened in Neil Young’s life, or even necessarily what it all meant. Clearly not ghostwritten, the book has a heightened stream of consciousness sensibility, with Young sharing whatever is on his mind, jumping between events and times and anecdotes with the attention span of a hummingbird. It’s preoccupied with Young’s own preoccupations: model trains, electric cars and trying to salvage audio fidelity in the digital age. It’s not written to be read; it reads, instead, exactly as it was written.

I’m guessing the copious asides and general directionless nature will frustrate most readers, but I found them fascinating. Not because the book’s content is interesting, mind you; the stories are regularly dull and almost always repetitive. But through them you get a sense of the sporadic rhythm of Young’s thought process, the fleeting interest he has in his various endeavours, a sensibility that infuses his best and his worst music. It’s a messy read, but it helps illuminate the messiness of Young’s career and the passionate-yet-uncommitted tone with which he approaches his work.

Waging Heavy Peace may be a letdown in its substance, but its real value is in its style. But those looking to learn Young’s story would be best to stick with Shakey.

David Byrne – How Music Works

A beautifully designed book — not that I’d expect less from Byrne — How Music Works is a strange beast. It’s got tons of autobiographical insight but it’s not strictly a story about Byrne’s career. It’s often touches on music history and theory but is nowhere near detailed enough to be a scholarly text. It’s flirts with performance analysis and industry talk, but it’s not a “how to make it in the music industry” book in the slightest.

Byrne’s book is all of these things and none of these things. The best description for How Music Works might be “autobiographical manifesto”: a survey of thoughts and considerations from a storied career in music, but structured in such a way that they cover the cultural, social and economic facets of music and music-making. Some of the chapter topics include digital recording, the value of collaboration, scene building and a rather comprehensive overview of the different sorts of recording contracts. Throughout, Byrne remains a compelling guide: clever, self-deprecating, but never talking too high or low to the reader.

Alas, despite his best efforts, the critical parts of the book never quite measure up to Byrne’s personal insights. (Although the numerous pot shots he takes at Adorno made me laugh quite a bit.) These memoir-esque sections are incredibly compelling if you’re a fan of Byrne’s work, as I am, but his writing and insights are general enough, and explained with enough detail, that it’s hardly a fans-only text. Whether he’s writing about collaborating with Brian Eno on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts or describing early bands learning to play at CBGB’s, the book offers one of the most exceptionally high insight-to-gossip ratios you’ll find in a personality-driven music book.

Rob Jovanovic – A Version of Reason: In Search of Richey Edwards

Most of you probably don’t know who Richey Edwards is, but he was kind of a big deal to me when I was 17 – or at least, his band was. I’ve written before about how important Wales’ Manic Street Preachers were to me as a teenager, and though I didn’t get into the band until well after Edwards mysterious disappearance in early 1995 – never found, presumed dead – his mythology was unquestionably part of the band’s appeal. I feel like most rock kids, even those of us who are almost adorably well-adjusted, have a phase where they fall under the spell of a tragic artist’s tragedy, even if only as a way to explore some of the darker, more fatalistic sides of pop stardom.

Jovanovic’s book makes the case for Edwards, the band’s co-lyricist and “designer,” as a worthy subject even if he hadn’t vanished. A Version of Reason illuminates a kid eager to belong in a world he didn’t fit with: not just rock music but adulthood, sex, stardom, the media spotlight. He couldn’t play guitar? He sure as hell was going to look good “playing” it, then. For all Edwards’ poor adjustments to each of these worlds, he never backs down from them. Until he disappears, of course. The book lays out the known facts about Edwards escape act and, in doing so, makes a convincing argument against a suicide (at least, not a suicide that particular day).

Sadly, the problem with writing about Edwards is that there’s really nothing new here: the band won’t talk about him anymore, and his family stays out of the discussion. The author’s distance from its subject leads him to over rely on his “searching for Richey, driving through Wales” conceit, not to mention the distracting mini-chapters detailing other tragic figures with echoes of Edwards. Ironically, the book was finished just as the band was starting to record Journal for Plague Lovers, its 2009 album that finally dove into Edwards’ final notebook for new lyrics. (It sounds like crass opportunism, but the record is a truly wonderful and impassioned tribute to Edwards.) If only Jovanovic been able to wait on his deadline a little longer, he might have had a more compelling coda.

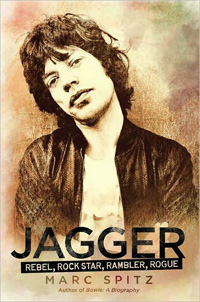

Marc Spitz – Jagger: Rebel, Rock Star, Rambler, Rogue

Spitz doesn’t have untimely death as an excuse for his distance from his subject: Sir Mick is not only alive, but decidedly kicking. No, in this case the problem is that for decades Jagger has been one of the most decidedly image-conscious performers in popular music. He rarely gives interviews. He’s never going to write an autobiography. He’s seen as cold, distant – almost literally the polar opposite of his bandmate, the more warmly received Keith Richards.

So in Jagger, Spitz isn’t really dealing with man so much as myth, although the two certainly intertwine throughout the book. Rather than give a narrative account of Jagger’s life, Spitz picks particular moments or eras that illustrate one of his arguments about the Stones’ frontman: how a 1964 show following James Brown forced a new passion in his performances; what can be learned from two shelved Stones artifacts (Truman Capote’s Rolling Stone article and the Cocksucker Blues film); how his appearance as himself in a 1978 TV special spoofing the Beatles was the real moment the 60s died.

I found Jagger a bit wanting, though that might not be Spitz’s fault: I find Mick Jagger a bit wanting, especially in the 21st century. One of the book’s best anecdotes is about a spontaneous blues session Jagger did in the 1990s with Rick Rubin and a band called the Red Devils that never saw the light of day. “Doom and Gloom,” released on last year’s latest Greatest Hits collection by the Stones, is easily their best single in years, and it’s based on a Jagger-written guitar riff. But Jagger, in general, seems to be so far beyond caring about impressing people creatively because he has no need for it. But oh, wouldn’t it be impressive if he did.

From McNutt Against the Music. Follow McNutt on Twitter.

Subscribe to Maisonneuve today.

Related on maisonneuve.org:

—Arcade Fire, Tune-Yards and Growing Up

—9/11, New York Music and Cultural Memory

—Taylor Swift, Carly Rae Jepsen and the Problem of Assessing Pop Music