Seamus Heaney: A Personal Remembrance

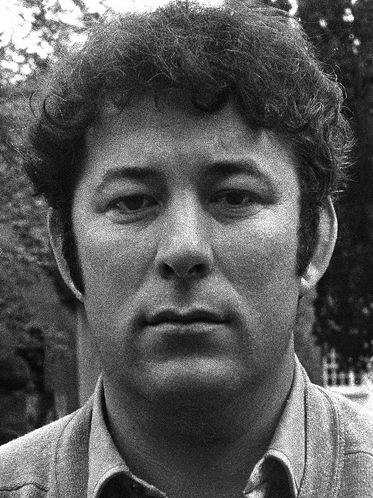

Seamus Heaney in 1970. Photograph by Simon Garbutt.

Six years ago, precisely a week after I moved to Montreal to go to school, my father called me to tell me that my grandmother had died that morning and I needed to fly to Belfast. Packing wildly, I grabbed a book of Seamus Heaney’s poetry and threw it into the bag. Pain and Ireland are two things in my life that must always be accompanied by poetry. Waiting for a connection in a Paris airport, I wept and read Heaney's poem about his younger brother's funeral:

When I came in, and I was embarrassed

By old men standing up to shake my hand

And tell me they were "sorry for my trouble,"

Whispers informed strangers I was the eldest,

Away at school,

- from “Mid-Term Break” (1966)

Last week, while walking home from the bar to my father’s house in my native Belfast, I came across a poetry reading. It was being hosted in someone’s front room a few doors down from ours. The reading was part of the excellent Household Belfast festival, and most of the assembled poets were from Queen’s University Belfast. The poetry was outstanding, and I imagine that many of those who read were from the university's Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry.

These two moments encapsulate, for me, what is so important about Heaney and why, after his death Friday morning in a Dublin hospital, he will be so missed. Ireland is a place where pain and the language needed to name it are always present. The need for language, and particularly poetry, to explain the unexplainable is obviously universal, but Irish poets know this need acutely. The young poets in the room on my father’s street in Belfast, the old men who greeted me at my grandmother’s wake using the same way as those at the wake of Heaney’s young brother: all are representative of the peculiarly Irish method of confronting trauma. These young Belfast poets are an essential part of a city, and indeed a whole generation, that is just coming out from under forty years of violence (known as "The Troubles"), and they know as well as anyone the debt they owe to Heaney.

The old men saying "sorry for your trouble" at a wake—with typical Irish understatement—are familiar to anyone who knows the country. To encounter pain and loss but still enjoy a bit of craic, and to admit how intertwined the two activities are: this separates humans from beasts. Heaney understood this better than most. Better yet, he wrote about it and enabled us to understand it.

That "trouble" comes from the mouths of Heaney’s old men at the wake, and also references forty years of conflict, is not an accident. An obituary writer from the Washington Post referred to the word as a “quaint local euphemism.” This is a misunderstanding. Rather, it is a deft usage of language, a code that signals to all who understand (which is everybody, in that part of Ireland) just how pregnant the word is. Michael Higgins, Ireland’s president and himself a poet, had it right when he said Heaney carried a “wry Northern-Irish dignity.”

To be able to celebrate a place like Belfast with festivals and poetry readings is a form of wry dignity, to be sure. The suffering has been immense, but sure, so has the craic.

In Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, he uses a word I've only ever heard spoken by people from the North of Ireland. Some dictionaries label the word as archaic, but my great-grandmother, who spent all her ninety-plus years in rural County Down on the other side of Lough Neagh from the farmhouse where Heaney grew up, used it often. The word is “thole” and technically means “to suffer.” But implied is a type of noble suffering, with eyes ahead not down, as bearing a cross or a burden.

Heaney is gone now, but his words will remain to teach future generations to thole.