Today, U.S. Income Inequality is Worse than in 17th-Century England

Forbes just put out its annual list of the four hundred richest Americans. Those four hundred people, it turns out, have more wealth than the poorest 150 million Americans combined.

That dismal statistic reminded me of another illustration of American wealth inequality.

A few years ago, I was in a class on British history at McGill, and the professor was giving an overview of the early modern English economy.

Titled peers and land-owning gentlemen made up just 1.4 percent of English and Welsh families in 1688, but they earned 16.2 percent of the national income, the professor said. His point was, essentially, "What a grotesquely unequal society!" (The figures are based on a contemporary estimate by pioneering statistician Gregory King.)

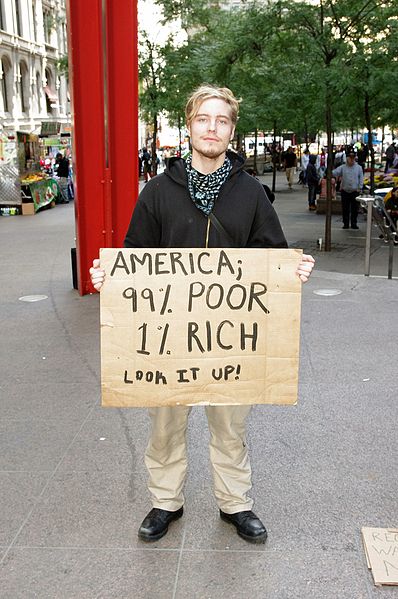

Strangely, 16.2 percent didn't seem like that big a slice of the pie. I've heard of worse, I thought. So I looked up the figures for the United States, and, as it happens, income inequality in America today is slightly worse—the top 1 percent of earners made 19.3 percent of the income.

Mind you, the 1688 figure refers to families. But, then again, that means more people were in on that 16.2 percent wealth chunk. And 17th century Britain had, you know, a formal aristocracy of about four hundred families ruling the country (along with a king). No one who didn't own property could vote, and aristocrats bribed those who did vote with massive banquets and kegs of wine, etc.

You would think America would distribute wealth more equitably than a place like that, what with universal adult suffrage and a progressive income tax and so on. But you would be wrong.