Falling in Love with the Universality of Alice Munro

On the inside cover of my edition of Alice Munro’s The Love of a Good Woman, there is the following line of text: “Alice Munro has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act.”

His right. Blink and you miss it. It’s a fitting reminder of Munro’s fictional world – the first sixty years of the Ontarian twentieth century – in which men are, almost unthinkingly, the only people with public status and legal authority.

Now Munro has become the thirteenth women to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in the 112 years since the award was established. Her fictional world was not, after all, fanciful. (Seven of those thirteen women have won since 1991, but still.)

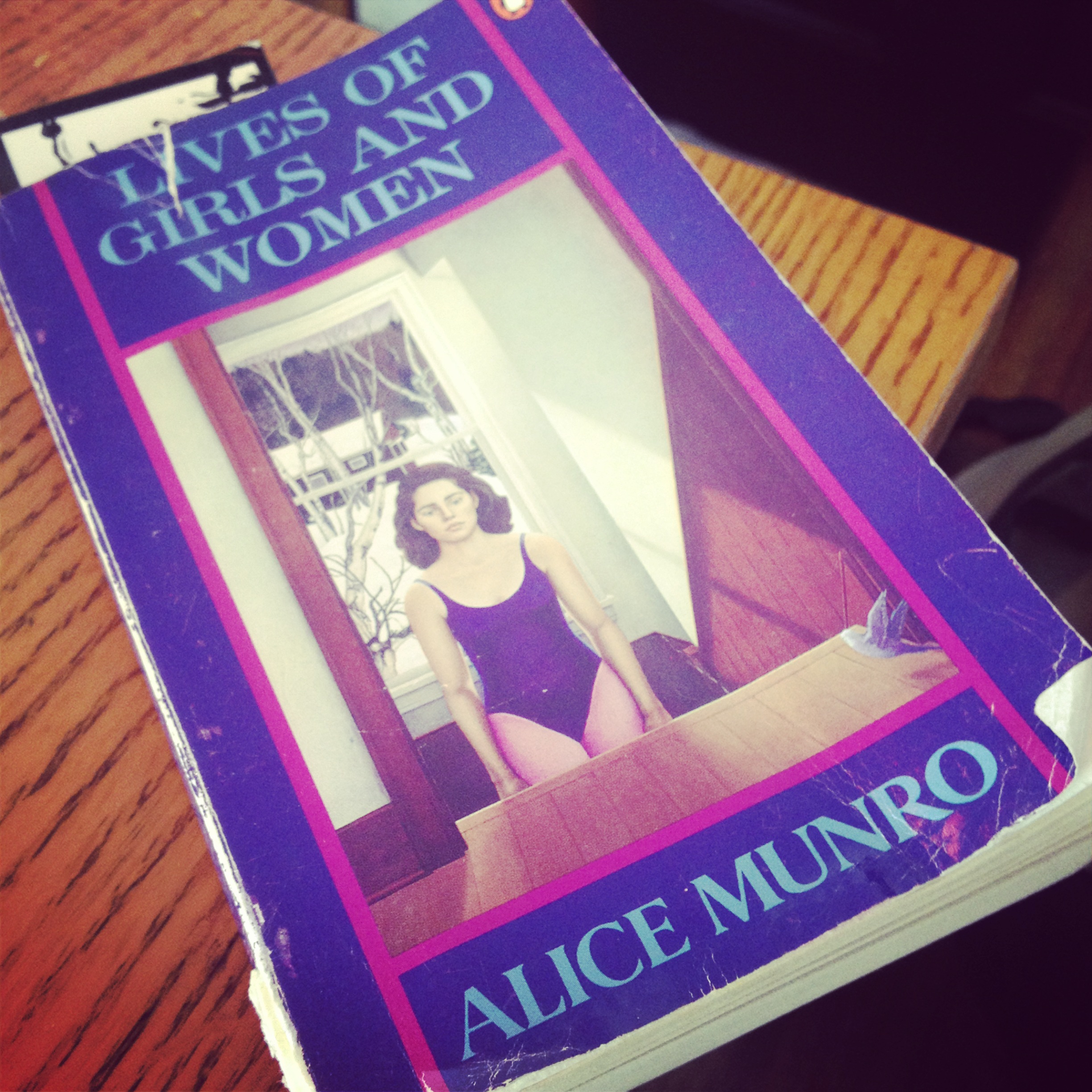

I fell in love with Munro this summer, devouring dozens of her stories. (She has never written a novel, properly speaking.) She is the bard of southern Ontario, where I’m from, and if you know southern Ontario you’ll understand what a hard place it is to be a bard for. Before the province became a haven for immigrants in the sixties, it was an arid, intolerant, joyless place, a land of King Billy-worshipping Orange Lodgers—Presbyterian, in a word.

Munro watched this drab landscape with a falcon’s eye – minutely, but from afar – and saw in it the universal: the longing for wider horizons, the inopportune times that wounds choose to resurface, the chaos wrought by sex, the uncomfortable knotting of dependence and resentment at the heart of filial love.

Christian Lorentzen wrote an attack on Munro in the London Review of Books this summer, right around the time when my infatuation with her was burrowing deepest, that still seems breathtakingly inane. He charged her with parochialism, writing, “Ordinary people turn out to live in a rural corner of Ontario between Toronto and Lake Huron, and to be white, Christian, prudish and dangling on a class rung somewhere between genteel poverty and middle-class comfort.” About how many great writers could you formulate that sentence? Replace Ontario with New Jersey, Mississippi, or Nigeria and you have Roth, Faulkner, and Achebe. Munro writes what she knows.

She is rightly celebrated as a feminist author, but it was always her depiction of the moral universe of southwestern Ontario, the world of my great-grandparents, that impressed me most. It can be a claustrophobic world—it certainly was for her protagonists, often teenage simulacrums of herself. But in Munro's hands, that world finds meaning beyond itself.

Once you’ve read a Munro story, it’s hard to limit yourself to just one.