Lou is Gone, and Lester Isn't Here to Write About It

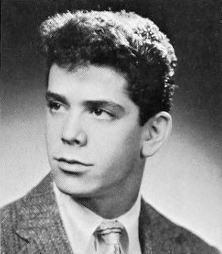

Lou Reed's high school yearbook photo.

Lester Bangs once interviewed Lou Reed in the dining room of a Holiday Inn. At the time, the musician was deep in the throes of alcoholism, a double Johnny Walker Black permanently affixed to his famous fingers. He was surrounded by friends and a jocular air of self-destruction. Bangs asked him when he planned to die.

“I would like to live to a ripe old age and raise watermelons in Wyoming,” he said.

Reed died yesterday, at the age of 71, on Long Island, where he lived with his wife Laurie Anderson.

Few relationships between critic and creator have been as well-documented as the one between Lester Bangs and Lou Reed. The musician was notorious for making reporters feel uncomfortable (following his death, slotted in between the tributes, were tweets linking to pieces in which Reed made mincemeat of eager reporters), and perhaps not surprising for a man who conjured myths for a living (city, sex, addiction, all become irresistible in the hands of Lou), he once said, “I don’t especially tell the truth most of the time anyway.”

But those who love his music will have trouble believing that. Anyone who has spent the last day and night revisiting Reed’s records has likely been suspended at once in the present and scattered across a thousand points of the past, recalling the moments woven into (and out of) his work. The music of Lou Reed does more than conjure the myth of the man, or even the myth of New York City. The music of Lou Reed conjures myth within ourselves, and I think I’m not alone in believing that it does so because there have been times in my life when it felt like the only thing that was true.

Reed’s career required documentation by someone whose talents also seemed to tiptoe right on the edge of otherworldly, yanked back down to the pavement by a refusal to ignore the intoxicating darkness of the everyday. Bangs was able to best capture Reed not only because of their twin ability to reach right through to the heart of something with the sparest (or most grandiose, or most alienating) strokes of their craft, but also because, put simply, he loved him. No one subscribed to the myth of Lou with more devotion than Lester (“hardcore fans like your reporter, who is something more in the realm of a fanatic”) and when Reed faltered, Bangs felt personally wounded. Those wounds meant he always approached the subject of his hero with a brutal honesty, sometimes provoking him to the point of rage in interviews, and some of Bangs’ best work was on Reed. These pieces inspire the same gastrointestinal shivers as the opening notes of “Heroin.”

When news of Reed’s death started filtering through the internet yesterday, I couldn’t help but feel doubly sad—that Reed was gone, and that Bangs wasn’t around to write about it. A musician as influential as Reed deserves a pitch-perfect-in-its-imperfection obituary, and the only man for the job died thirty-two years before his creative foil. What would Lester have made of these last three decades of Lou’s life?

In 1980, in a piece loosely called “Untitled Notes on Lou Reed,” Bangs wrote, “You know your hatred is just like anybody else’s. The real question is what to live for. And I can’t answer it. Except another one of your records. And another chance for me to write. Art for art’s sake, corny as all that.”