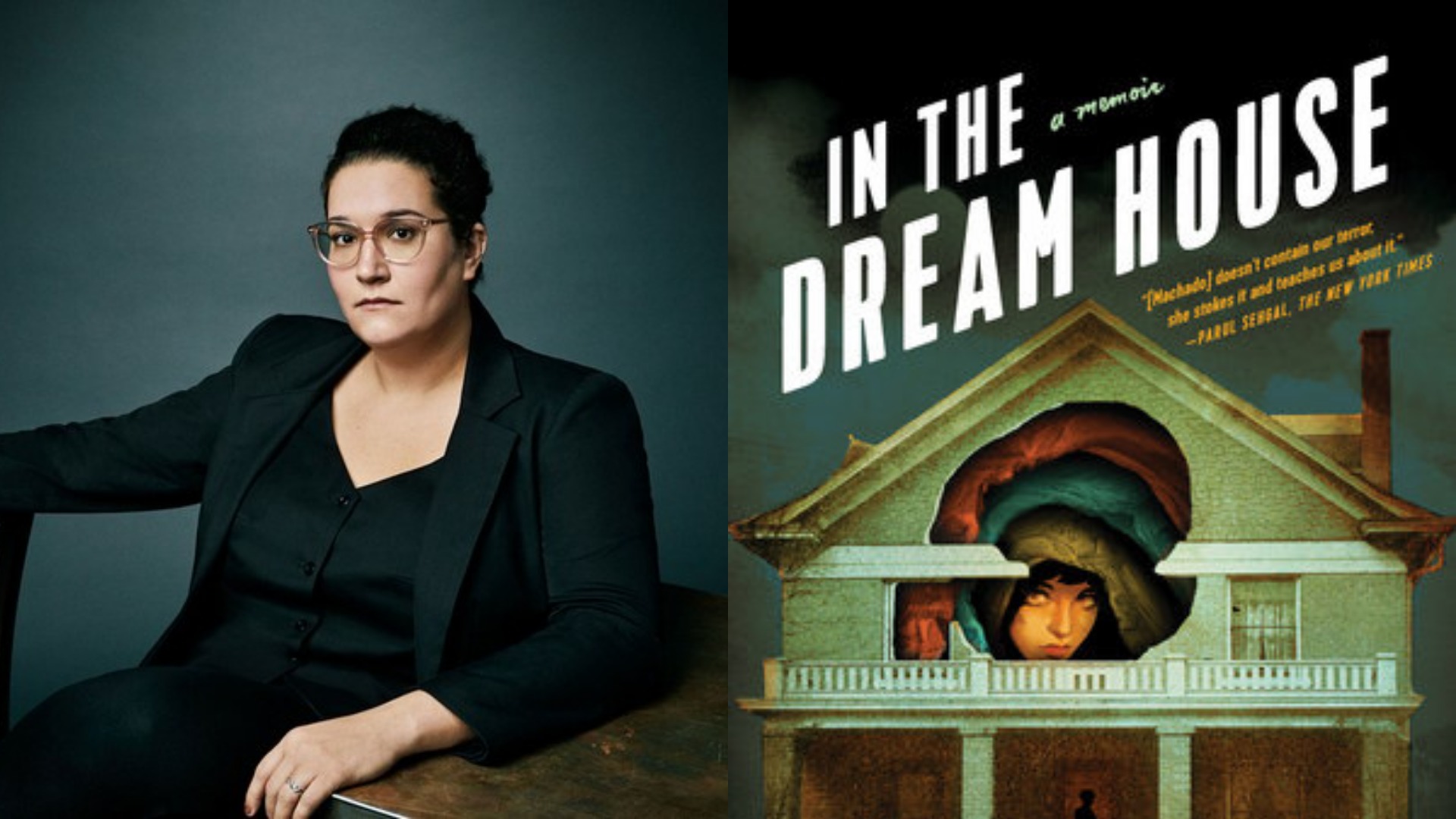

The House is a Space of Living Metaphor: An Interview with Carmen Maria Machado

In Carmen Maria Machado’s debut collection of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties, women’s bodies become sites of horror. Delicate ribbons keep their heads from falling off their shoulders; invasive surgeries bring them closer to the ideal figures they imagine for themselves; incurable diseases make their flesh and bone fade away until they vanish altogether. But the true terrors in Machado’s stories lie beneath the surface, in the ordinary traumas women experience, hidden from sight.

Machado’s new memoir, In the Dream House (Strange Light), brings one of those experiences to light. She recounts how, nearly a decade ago, she lived through an abusive relationship with another woman, immersing readers in the psychological landscape of the “Dream House” where it took place. Machado is writing to fill an “archival silence,” a cultural record that fails to account for domestic abuse in queer relationships.

Her book is an experiment in form, with each chapter telling the story through a different literary genre or trope. There is, for instance, “Dream House as Memory Palace,” “Dream House as Erotica,” “Dream House as Natural Disaster.” Machado intertwines her narrative with essays on queer theory and pop culture. She unearths historical records of intimate partner violence in lesbian relationships. She annotates the cycle of abuse with footnotes referencing motifs from folk tales—an unsettling acknowledgement of the ubiquity of this kind of violence.

“I speak into the silence,” she writes. “I cast the stone of my story into a vast crevice; measure the emptiness by its small sound.” And her story, like the Dream House that holds it, is expansive and unforgettable—it will haunt you, leave you rearranged. I spoke with Machado in December when she visited Montreal.

Madi Haslam: Much of the book is written in second person, addressed to your past self. As a reader, I found that choice created a deep sense of dissociation but also of intimacy. How did the choice serve you as a writer?

Carmen Maria Machado: When I first started writing the book, I handed in a skeletal draft that was entirely in second person. It was just the personal memoir events, without the criticism or the essays. My editor said to me, "So, this is all in second person." And I was like, “Is it? Holy shit." I had done it almost unintentionally. My editor told me that I could keep it in second person, but he wanted to make sure I was doing it with purpose, that it wasn’t just a reflex of trauma or distancing. So I began to move those sections into first person, and I really struggled. I would read the sections out loud, and they didn't sound right. So I was like, okay, this is resisting me. It doesn't want to be in first person.

There’s this gorgeous novel that I love called We the Animals by Justin Torres and it's told in the plural first voice. It’s these brothers and it's this we. And then there's an act of trauma in the book that splits the point of view until it becomes a you and then an I and a he. I was really interested in the way in which trauma acted as this sort of lightning bolt that goes to the marrow of the story, where it splits apart. The very perspective is altered by the trauma. So I took a page from that book.

In my own book, very early on, I do this act of separation where I talk about this first-person Carmen—that's me—and the second-person Carmen—that's like this past version of myself that can't access any of the knowledge that I have. And she is constantly turning on this hamster wheel of pain, trapped in the past. Who I can speak to is the you, but it's different than me and separate from me. She’s stuck there forever and there's nothing I can do about it, so it’s sort of honouring that wall.

MH: How did you come to fracture the story using different genres and tropes?

CMM: I was teaching in the summer writing workshop in Iowa City, teaching teenagers. I talk a lot about genre with my students: horror, science fiction, fantasy, magical realism. At some point, I was walking in Iowa City and thinking to myself about this project that I'd been wanting to work on. I had tried to tell it in a straightforward manner and it just never worked. Everything I wrote was awful. So I just started thinking about it in this sort of fragmented way. Why not a haunted house story? Why not an epic fantasy? And then once I did that, the whole thing kind of fell out of me like a wet baby giraffe; it fell from a great distance and it was gross, but it had its sense of what it was going to be.

For me, form is the way in which one can light upon what is going to make a story special or what's going to make it itself. It's like the story is still eluding me in some way until I hit upon a certain idea or a certain form. After I know what that is, the work will push me closer and closer to what I want the story to be.

MH: The structure of the Dream House itself—the place where your ex lived in Indiana—is also, quite literally, lending itself to the form. You have this line in the book: “Places are never just places in a piece of writing. Setting is not inert. It is activated by a point of view.” When did you realize the house had to come alive to tell this story?

CMM: I think about that house a lot, and it's funny because it's just not a very special house. It's quite ordinary, maybe even kind of gross—it’s in a college town, it’s not very old. I’m sure it had its charms and its secrets once upon a time, but it wasn’t some rumbling manor. What was interesting to me was wondering: how was that house a haunted house?

You know, my parents got divorced a few years ago and they sold my childhood home, which they built in like 1999, so it's a relatively new house, very ugly, very American suburban. But even though it wasn’t a creaky old Victorian manor, it had its own metaphors built into it. And the house came to embody and reflect certain psychological qualities of the people who live there. The house is a space of living metaphor—not a sort of facade of metaphor—but a thing that comes alive because of what's happening there, and who is there, and what it means to be there at a certain moment. There’s a way in which architecture can sort of receive us and turn parts of it back on us, give us a kind of context.

MH: Have you always thought about haunted houses in that way?

CMM: Many haunted house narratives that I read, or rather that I see in film, are kind of insufficient. They're not as interesting as I want them to be because I do think that as a genre, when you think about the house—the space of domesticity—you think about the gothic, you think about women and their relationship with interior space and the home, and how traditionally they've been assigned domestic roles. Architecture receives women’s pain and reflects their pain and bottles it and holds it. And then there are the false promises of domesticity: the ways in which it can be interrupted or turn perverted or manipulated. So it feels like a natural space of interrogation.

MH: There’s such a strong sense of being trapped inside the Dream House throughout the book, and it’s recreated brilliantly through the form. There’s “Dream House as Word Problem,” which poses a series of questions with no possible answers, and “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure,” which is full of cyclical choices and ultimately can’t be escaped. What inspired you to use those devices?

CMM: I've been really interested in formal constraints for a long time and some of them are very Oulipian. I also have the Lipogram in the book (which entirely omits the use of the letter e in the chapter), which I'm really interested in. It’s a joke-poking form and I feel like it works so well for this book in particular because when you read it out loud, it sounds stilted and it sounds weird because something is being omitted.

For the Choose Your Own Adventure part, I had written in my notebook, “Gaslight the reader?” I wanted the text to be hostile somewhere and I wanted to make the reader feel kind of unbalanced and manipulated. The structure gives you an illusion of choice. It pretends as if you have a decision to make but you don't. It's a pre-prescribed set of choices being made by some other force and you can get led down the wrong path and die or get caught or get trapped. And so, like the story, you get stuck in a circle. You can’t make the right choice and the story yells at you if you break the rules. Weirdly, I just got a very sweet email from the people at Chooseco—the company that owns the Choose Your Own Adventure brand—saying they were really touched by the way I used the structure. Which was surprising, because it’s a brand for children.

MH: And you’re almost perverting it.

CMM: Totally.

MH: At one point, you call writing the book an "act of resurrection.” Did the process change your relationship to memory, or your understanding of how abuse can disrupt memory?

CMM: With all writing of memoir, when you're writing about the past, it’s always a bit elusive. It's sort of like the house—animated by perspective. And then you add trauma, and you add abuse and more time and distance and perspective. I don’t think any writer would say their story is one hundred percent accurate. So it becomes about recreating it as faithfully as possible. There was a point in writing the book where there was a scene that I had written where I was walking in one direction, and then at some point, I realized that suddenly my brain had inverted the direction that I was walking in it, which was incidental, but it bugged me. It really fucked me up and I was going in circles asking myself what it meant that I couldn’t remember which direction I was walking. There's a lot of anxiety balled up in that.

When you think about how trauma affects your memory, you know that sometimes there are things that you just don't remember. The brain has a sort of inherent capriciousness in the way it reconstructs things. That’s why I find fiction much less stressful—if I half-remember something, I can just do whatever I want. With non-fiction, it becomes this ethical quandary: how do I do this in a way that makes sense to me and in a way that also feels accurate and correct?

MH: You write so beautifully about the ways in which parts of your body are beginning to forget what happened in the Dream House while other parts hold on to it—how abuse can fragment people in a way that almost changes their DNA. I keep coming back to these two scenes that take place in the near-present. In one, you accidentally drop a snail and break its shell and are filled with all this grief. And then just a few chapters later, you’re running around your apartment crunching cockroaches with your bare hands. Do you try to reconcile those sort of disparate parts of yourself that emerge as you’re processing what happened?

CMM: I think it's the nature of processing and—this is cliche—but you know, people contain multitudes. The weird thing about this book is putting myself so obviously on display. With non-fiction, there’s nowhere to hide. At one point, I use this metaphor about how cells turn over unevenly to describe processing things in different ways. Most parts of me are kind of like, “Oh my ex, fuck her, you know?” And then there are parts of me that reflexively will do something that she taught me to do and I'll catch myself doing it. How weird that parts of me are still responding to this old stimuli. I don’t know how to reconcile that. In one breath, I'm so far from the person I was when we were together that she's a totally separate person; and then sometimes, in some ways, it’s like she's nestled up in some corner of my collarbone.

MH: How did you—or did you—get over your fear of writing this book? There’s this myth that memoir-writing is an inherently cathartic process, but was that the case for you?

CMM: Oh, I didn't get over any fear. I just did it. I'm a deeply fearful person and I’m afraid of things, but I try to do them anyway or I do my best. It's okay to say I'm afraid, but I can't let that rule my life. It's about acknowledging my fears and then pushing up against them as best as I can. I was terrified as a child. I was a hypochondriac and I read books about illness. I was afraid of the dark and of monsters and I would read horror novels. I would work myself into a complete frenzy. I couldn't explain it.

I am afraid of this book still. I was afraid of writing it. It was horrible. I barely survived getting through the writing process. I don’t know why people say it’s cathartic. It was very painful and it really just brought me very close to my own insufficiencies and my own fears and my own traumas—the ways in which I have not recovered, the ways in which I have this inherent kind of damage. I don't know if I would do it again. But I kind of feel like I needed to get this book out of my system, or I needed to get out of my own way. There are all these other books I want to write, all this fiction, and I feel like I had to put this book somewhere.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.