Waterwords: A Cross-Border Conversation with Fred Wah, rita wong, Khairani Barokka and a rawlings

This series brings together writers in different parts of the world to discuss their writing and inspirations.

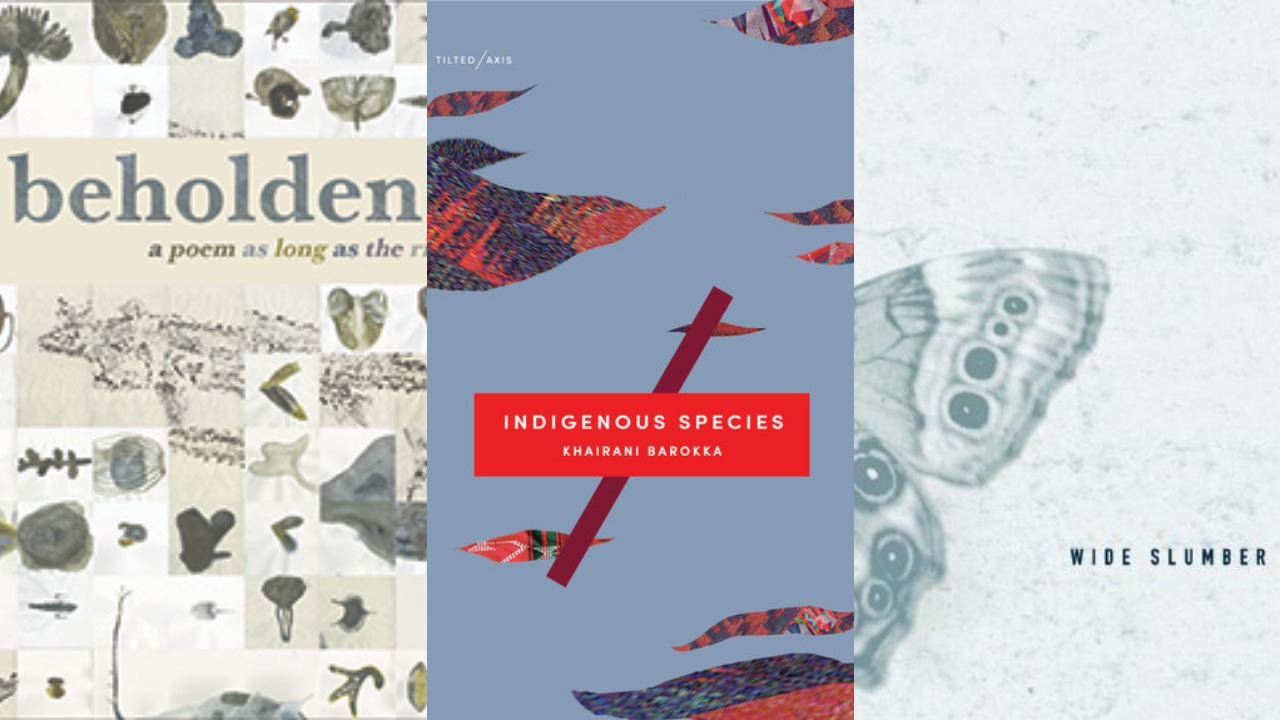

Here, Elee Kraljii Gardiner talks to four poets working with the theme of water, and not only in their poetry. Fred Wah and rita wong, both based in British Columbia, collaborated on beholden: a poem as long as the river. London-based Indonesian author Khairani Barokka wrote Indigenous Species, which combines Braille with text and collage to create a river-themed narrative. Icelandic-Canadian artist a rawlings researches ecological issues through poetry, performance and interdisciplinary art.

Elee Kraljii Gardiner: Could you each speak to the impulse behind your projects? What drew you to this waterwork?

Khairani Barokka: In Indigenous Species, I preface the long poem with an introduction that recalls a very distinct sensory memory: I was travelling on a narrow boat on a river in Kalimantan, surrounded by rainforest and the sound of continuous buzzsaws. It’s a memory that is distilled in the book, fuelled by a sense of rage at what is happening in Indonesia. Rage is for sure the defining feeling here, as well as a sense of being abducted—as the narrator is—along a river of destruction.

I wanted the narrator to speak with assurance, with the knowledge that she has a semblance of control over her surroundings, at least a control over her need to escape. The art I made and the words in Indigenous were also very much influenced by my personal rage at being continually disbelieved, over years, about the acute chronic pain in my body. I connected that with the anger at what is happening in the world around us. I felt it important to convey environmental messages that weren’t whitewashed or tinged with corporate environmentalism, or the financialization of nature. I was very inspired by my parents in particular, whom the book is dedicated to, and who have long been involved in grassroots environmental justice efforts.

My full-length poetry collection, Rope, is pleasantly categorized in libraries and stores as “sea poetry.” As it followed Indigenous Species, I’ve just realized the poetry is a river of rage turning into a sea, where disquiet and travel are taken to a level where it’s possible to sense calm. With both books, I don’t remember explicitly thinking “I want to write about water,” but they found their own shape in liquid bodies quite naturally. Did any of you begin with thinking about water specifically?

Fred Wah: I grew up alongside both the Columbia and the Kootenay (a tributary of the Columbia) rivers, in Trail and Nelson, British Columbia. During the 1960s there was disastrous upheaval on the rivers, particularly the devastation of the Arrow Lakes, but also dam construction and the industrial transition of the rivers into reservoirs. This upheaval was the consequence of the Columbia River Treaty, signed by Canada and the US in 1964. In 2014, the treaty was up for renegotiation and it was because of that I became re-engaged with the central geography of my life.

My poetic attention to the renegotiation began in 2013 during my tenure as Parliamentary Poet Laureate, when I was asked by a former MLA to consider writing about this issue. One of the first things this “re-engagement” with the river taught me is how silently my own political and cultural memory had lapsed. I had become numb to the human and ecological distortions that had minutely settled into the life around the watersheds. The second thing I became aware of was that, subconsciously, water (creeks, rivers, lakes, etc.) was a significant trope through most of my poetry over the past fifty years. I only noticed this as a kind of déjà-vu in trying to write into the project that became beholden. A major part of writing about the Columbia has been, for me, recuperating an imagination I had forgotten.

rita knew I was interested in this matter and she invited me to join “River Relations,” a wonderful group of artists, students and academics who have worked together on the Columbia for several years. rita’s and my collaboration was not so much textual as through conversation and visiting the river together and in our research group.

rita wong: I’ve been learning with and working with water for the past decade. Dorothy Christian and I co-edited an anthology called Downstream: Reimagining Water, arising from a gathering we organized back in 2012. Water is what drives my books undercurrent and perpetual, as well as my work around protecting waterways. In my first book of poems, monkeypuzzle, I wrote poems responding to my experiences when I lived in China for a year, including taking a trip along the Yangtze River, which led me to oppose the building of the Three Gorges Dam. Here I am, more than twenty years later, adamantly opposed to the Site C Dam because it would destroy what precious remains of the Peace River exist. I’ve also visited the Wedzin Kwa (the river the Unist’ot’en are protecting) and was arrested and imprisoned for my opposition to the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion. It was gratifying to see the UN’s committee against racism recently come out against all three of these projects.

a rawlings: Two water-specific projects rise in my mind. From 2011 to 2014, I pursued a master’s in Environmental Ethics and Natural Resource Management at the University of Iceland. Midway through my studies, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. During the subsequent surgeries and chemotherapy, I found myself compelled to visit glaciers in the countryside. These glaciers, of course, I’d visited numerous times in previous years, and I had already been researching the imminent disappearance of all of Iceland’s glaciers, predicted by glaciologists to occur in the next 150 to two hundred years. After my mastectomy and each round of chemotherapy, I travelled to a different glacial moraine, lagoon or vista. At each site, I performed a ritual—two bodies (glacial, human) juxtaposed in their irrefutable transformations. Each ritual was performed bare-chested, surgery scars facing audible melt.

In sight of Snæfellsjökull, I cut the length of my long braid and left it tucked behind the skull of an arctic fox whose body I’d buried in a lava field the previous summer. On Sólheimajökull’s glacial lagoon, I climbed atop an ash-striped iceberg. Sachiko Murakami photographed me cutting my remaining hair close to my head. Along Jökulsárlón’s black-sand beach, I photographed pieces of stranded icebergs and other human litter, in search of my excised breast meat. Each ecosystem interaction was photographed and reflected in text. I wrote the play Áfall / Trauma interlaced with these rituals, and produced digital poems Jöklar and RUSL about climate breakdown and cancer treatment. Finally, I completed my master’s thesis focusing on the plight of Icelandic glaciers through the lens of ecolinguistic activism.

More recently, in my PhD dissertation at University of Glasgow, I’ve focused on how to perform geochronology—the branch of geology concerned with the dating of rock formations and geological events. With increased storminess, glacial melt, rising ocean levels, ocean acidification, and dramatic change to cohabiting species—all related to the climate crisis—foreshores are a place where geomorphological acts and humans meet. In performances, we collect plastic bags that have washed ashore and knit them. We move in counterclockwise circles to partner with the movement of air currents over the North Atlantic. The resulting performance scores are published in my book Sound of Mull.

EKG: How do you feel about your work on the page versus as you articulate it, or as listeners hear about it?

KB: Indigenous actually began as a performance poem, as part of a residency I did in Melbourne. There was a night where we had to perform works about animals, and I wrote the poem for it in Jakarta. The poem became an illustrated work because, as a visual artist, I’d always envisioned digital art with animals being projected behind me as I performed, and also decided to tackle the question, “Why is there no good example I can find of Braille, visual art, and text in one book?” Being a disabled artist means multi-sensorial work is something I think about a lot. So it’s always an interdisciplinary art performance, an accessible poetry performance, which I do enjoy taking to people, performing it.

FW: The work on the page for beholden was specific for each of us. Nick Conbere, project manager and artist, brilliantly provided us with a digitally treated map of the Columbia. rita chose to write by hand along the river and Nick provided me with a text path in Adobe Illustrator. The composition, for me, was multi-layered; conceptual, linguistic, geographical, and material. Some of the time I wrote with specific images of having been there. I also tried to position my writing presence to not speak for the river but rather listen for a language that moved in communion. Metaphor was impossible to avoid yet I was wary of it.

ar: When a work appears both on the page and embodied, they inter-depend. Some works, though, manifest as visual entities first. Wide slumber for lepidopterists, my second book, worked in this way. I spent five years composing this book as a page-based long poem. Upon its completion, I strategized how to lift the text into performance. Other works start as sound or movement (as with several performance scores in Sound of Mull), and move later to text. And there are, of course, some works which live solely within performance or solely as visual entities.

rw: It depends on the work. Some poems are born for the page, but when I can hear the rhythm and perform it the way I hear it in my body, that works on more levels.

EKG: I’m curious about the relationship to history in your writing. How do you react to histories in your poetry?

KB: Always grappling with histories as emotional imprints, sensorial and burrowed in there among our organs, and also as a process we are part of, continuously creating. My cultural heritages are not ones of linear time and space—which is a comforting thought, that deities and ourselves exist in permutations of past, present, future. I am leaning into that.

FW: History is the memory of time, as one of my teachers said. Remembering the future has been much on my mind, now late in my life. So memory, more than history, seems pertinent to me right now. The witnessing of the brain in memory. Charles Olson in his poem “A Later Note on Letter 15” wrote, “‘istorin, which makes any one’s acts a finding out for him or her/ self, in other words restores the traum: that we act somewhere.” ‘Istorine, to find out for oneself makes history, as a verb, present and now. Environmental history, in that sense, includes deep time and only the imagination.

rw: History matters. I’ve benefited so much from what those before me have written. If I can contribute to continuing the dialogue with histories (herstories) that have been marginalized, then that’s something I hope can be helpful to others, now or yet to come. I don’t see time as linear, but more as cyclical, and what Wayde Compton writes about tidalectics (in the introduction to Bluesprint: an anthology of Black British Columbian literature and orature) comes to mind on this:

“The Barbadian poet and theorist Kamau Brathwaite coined the term tidalectics to describe an Africanist model for thinking about history … Tidalectics describes a way of seeing history as a palimpsest, where generations overlap generations, and eras wash over eras like a tide on a stretch of beach … In a European framework, the past is something to be gotten over, something to be improved upon; in tidalectics, we do not improve upon the past, but are ourselves versions of the past.”

This term is also useful for thinking about one’s relationship to the body of literature and the culture that precedes us. Instead of the arrogance that can be implicit within making it new, to think about how one might approach poetry humbly, learning from the examples before, repeating them with a difference, or learning from the ecosystems around us how not to waste, how to attend to, what we encounter in our daily lives.

EKG: Do you care to speak about hybridity (of genre or race or language or geography or citizenship or belief or body or purpose...) as it appears in your projects?

KB: It was important that Indigenous feature both “fake/flat Braille” to show sighted people what we need to consider more often, as well as English text and non-italicized, untranslated words in Bahasa Indonesia and Baso Minang. It was important that the chapters in Rope were numbered in Baso Minang and Boso Jowo (Javanese), and that it contain words in four of the languages that have shaped my history (Indonesian, English, Baso Minang and Boso Jowo). I don’t want to deny different parts of myself, whether in allusions to being Muslim where Arabic words pop up in Rope, or the refusal to italicize words, deciding for both books that there would be a glossary only at the end. Indonesia is extremely complex culturally, with hundreds of languages and cultures, so I also think it’s important to query this idea of “national representation,” and instead have a sense of geography that doesn’t come from artificial boundaries. I am always trying to re-remind myself of that, of the fluidity of so much we take as fixed.

FW: Too big a topic for me. I’ve spent at least half my writing life on this. The advantage to standing in the doorway is that you can see both rooms, inside and out. My book Faking It: Poetics and Hybridity still provides me with that discourse I’ve worked so much on.

EKG: What ideas are you working with these days? Where can we find you next?

KB: Fiction, poetry, hybrid genres, more image-text combos. Water will still be a feature! As are our anxieties, personal and planet-large.

FW: I’ve spent the past two years putting together Music at the Heart of Thinking for a Talonbooks publication. This collates two earlier out-of-print books with later segments of a long poem project started in the early eighties. It is a chunky book of improvised and playful responses to other texts and art. Should be out Fall 2020.

rw: I am focused on whatever I can do to protect the Peace Valley from being destroyed by the Site C dam (I am part of a group in Vancouver called “FightC” working to stop the dam), and to protect the Salish Sea from destruction by a pipeline expansion no one can afford (see the group “Mountain Protectors” on Facebook). Words lead me to actions. That’s where I am at the moment.

Fred Wah lives in Vancouver and in the West Kootenays. Recent books include Sentenced to Light, his collaborations with visual artists, and is a door, a series of poems about hybridity. High Muck a Muck: Playing Chinese, An Interactive Poem, is available online at highmuckamuck.ca. Scree: The Collected Earlier Poems, 1962-1991 (2015) was followed by a collaboration with rita wong, beholden: a poem as long as the river (2018). See also riverrelations.ca. A collected long poem, Music at the Heart of Thinking, will be published in 2020.

rita wong is the author of five books of poetry and an associate professor in the Faculty of Culture and Community at Emily Carr University of Art and Design on the unceded Coast Salish territories also known as Vancouver. She co-edited the anthology Downstream: Reimagining Water with Dorothy Christian.

Khairani Barokka is an Indonesian writer and artist in London whose work has been presented extensively in fifteen countries. She was an NYU Tisch Departmental Fellow, and Modern Poetry in Translation’s inaugural Poet-in-Residence. She is a UNFPA Indonesian Young Leader Driving Social Change, and is Researcher-in-Residence at UAL’s Decolonising Arts Institute. Okka is most recently co-editor of Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back (Nine Arches), author-illustrator of Indigenous Species (Tilted Axis), and author of Rope (Nine Arches). Her latest exhibition was Annah: Nomenclature (ICA). khairanibarokka.com

a rawlings is a Canadian-Icelandic interdisciplinary artist whose books include Wide slumber for lepidopterists (Coach House Books), Gibber (online), o w n (CUE BOOKS), si tu (MaMa Multimedijalni Institut), and Sound of Mull (Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology). Her book Wide slumber was adapted to music theatre by Valgeir Sigurðsson and VaVaVoom. Her libretti include Bodiless (for composer Gabrielle Herbst) and Longitude (for Davíð Brynjar Franzson). rawlings’ Áfall / Trauma was shortlisted for the Leslie Scalapino Award for Innovative Women Playwrights. She is one-half of the performance duo Völva with Maja Jantar and one-half of the new music duo Moss Moss Not Moss with Rebecca Bruton. rawlings is the recipient of a Chalmers Arts Fellowship and held the position of Queensland Poet-in-Residence. rawlings loves in Iceland. More: www.arawlings.is

Elee Kraljii Gardiner is the editor of Against Death: 35 Essays on Living, an outgrowth of her second poetry collection, Trauma Head, about her experience with vertebral artery dissection and stroke. Her other books are the poetry collection serpentine loop and the anthology V6A: Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Originally from Boston, Elee now lives in Vancouver on the traditional and unceded territories of the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh and Musqueam Peoples.