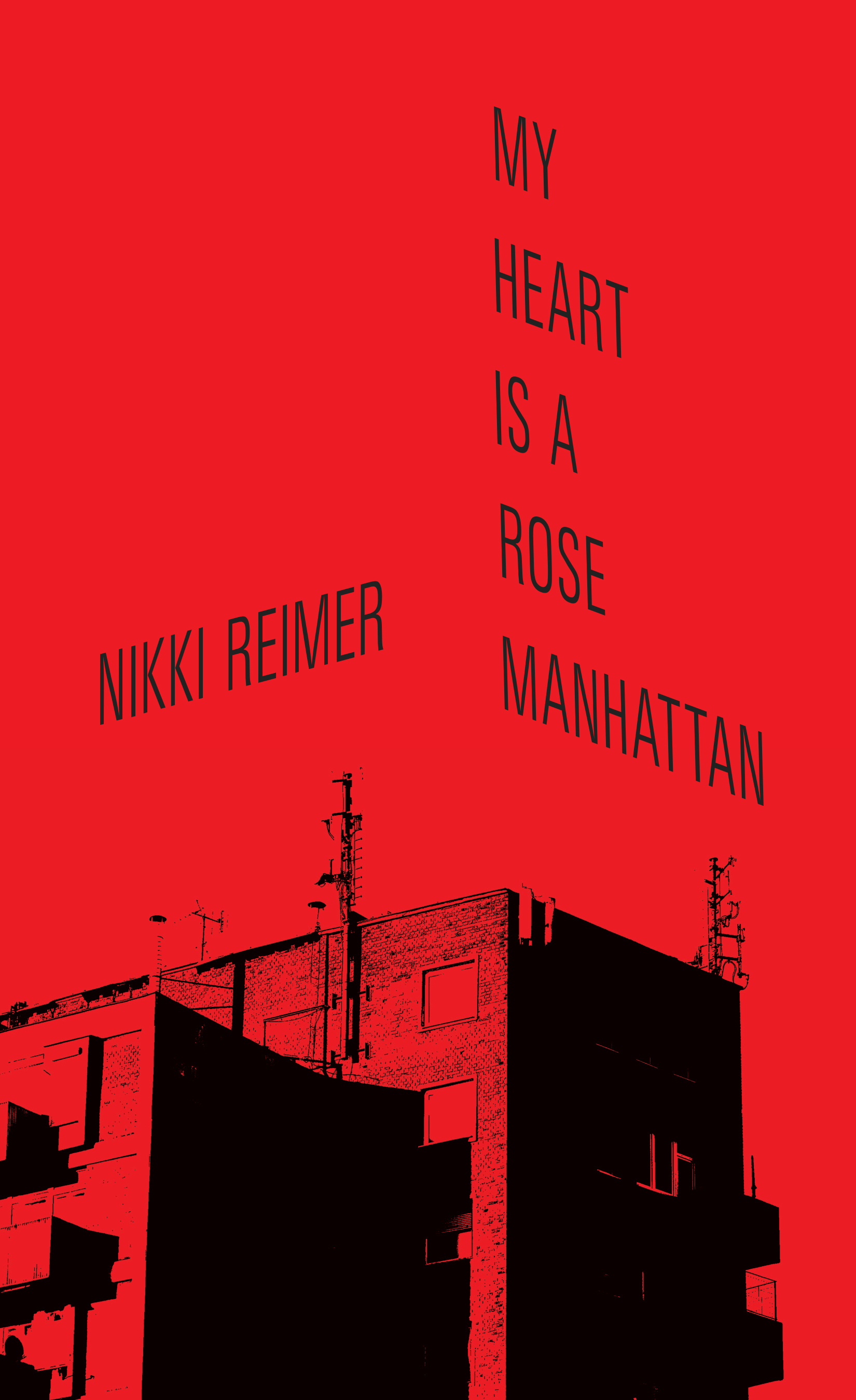

Conversations in Quarantine: Nikki Reimer

Nikki Reimer is a non-fiction writer and poet, whose most recent book, My Heart Is a Rose Manhattan, came out last year with Talonbooks. She usually lives in Calgary, Alberta, on the traditional territories of the Treaty 7 People. Her practice explores emotion, feminist issues, urban life, loss and grief, and politics—though her work is also darkly funny and absurd.

andrea bennett: Could you tell me a bit about what your life—work, writing, home—looked like before quarantine, and what it looks like now?

Nikki Reimer: Before: I was working 9–5 weekdays at my day job, and regularly dropping in to dance, yoga and Pilates classes. I had just turned forty, had just completed an online writing workshop, and was feeling reinvigorated in my practice and eager to get back to a project that had been languishing. I was seeing friends, dropping into my local bookstore and coffee shop, and going to art openings.

Now: I had some trauma reactions at the start of quarantine and spent the first few weeks alternately weeping and sleeping, but that seems to have levelled off. On April 19, I moved out to Claresholm, Alberta, where my spouse had been staying at his father’s place. My father-in-law has cancer and is in hospital here. I work, have too many Zoom and Microsoft team meetings, attend online yoga and stitch-and-bitch. I cuddle my cats and sit outside the window at the hospital to visit my spouse’s dad. I couldn’t focus at first but have lately been reading and noodling on some pandemic-times poems.

ab: There’s a set of lines close to the beginning of your most recent book that reads, “my work will not create new imaginative / worlds to help guide the way / out from the ruins of late capitalism.” I think one thing your work does do—as well as sharing a sort of embodied poetic expression of grief—is open imaginative avenues for criticism of capitalism, often through a really funny, smart, ears-open manipulation of the language that surrounds us in marketing, nation-building, etc. Given that, I’m wondering if you could share some of the language or positioning or cultural moments that you’ve been thinking about over the past couple months, as the pandemic has unfolded?

NR: I’m interested in anxiety as contagion; the emotional tones of the present moment; how we are caring for or abandoning each other in the present moment; the insatiable machinations of capitalism and the rise of fascism; the quiet moments. Witnessing the public collective grief has also been a trip. I feel the same kind of lawless drifting, meaninglessness of time, summer-camp-in-hell brushes with mortality that I felt after my brother died, only now the whole world is in on it too, which is wigging me out. When Chris died it was comforting to have occasional interactions with people who were still mired in quotidian reality. (When I wasn’t hating their smug aliveness, let’s be honest).

And then the memes and actions of how we are collectively seeking comfort now.

ab: Do you have a favourite pandemic meme?

NR: These aren’t memes, but there was an early joke that I couldn’t find again when I went looking for it, but it was a tweet, along the lines of:

My boss: How is everyone doing?

Me, mouth full of sour soothers: Very bad.

The visual of drowning in a substance while copping to the fact of not coping is just so hilarious to me. My second favourite is the “choose your quarantine character” e.g.,

ab: What has it been like to help care for a loved one with cancer during a pandemic? I think I recently saw a picture of you and your spouse camped out on the lawn outside the hospital, and I’m wondering if you can talk a bit about that.

NR: It’s a lot. My spouse spends most of the day seated outside the hospital on a bench that he drags over to the window. He tacks up a tarp to block the sun’s glare so they can look at each other, and they talk on the phone. I go to visit when I can. His cancer is incurable and they’re having trouble managing his pain. I try not to think of him having to die alone, but I know that it’s a possibility. And of course my father-in-law still wants to look after things at home—it’s almost 10 p.m. and he just called to talk about a tree that needs pruning in the yard. The situation feels impossible but all we can do is manage the immediate crisis, and then move on to the next, and try to rest when we can.

Postscript: Nikki’s father-in-law died on May 2, 2020. Her husband was able to spend some time with his father in his hospital room before he passed.